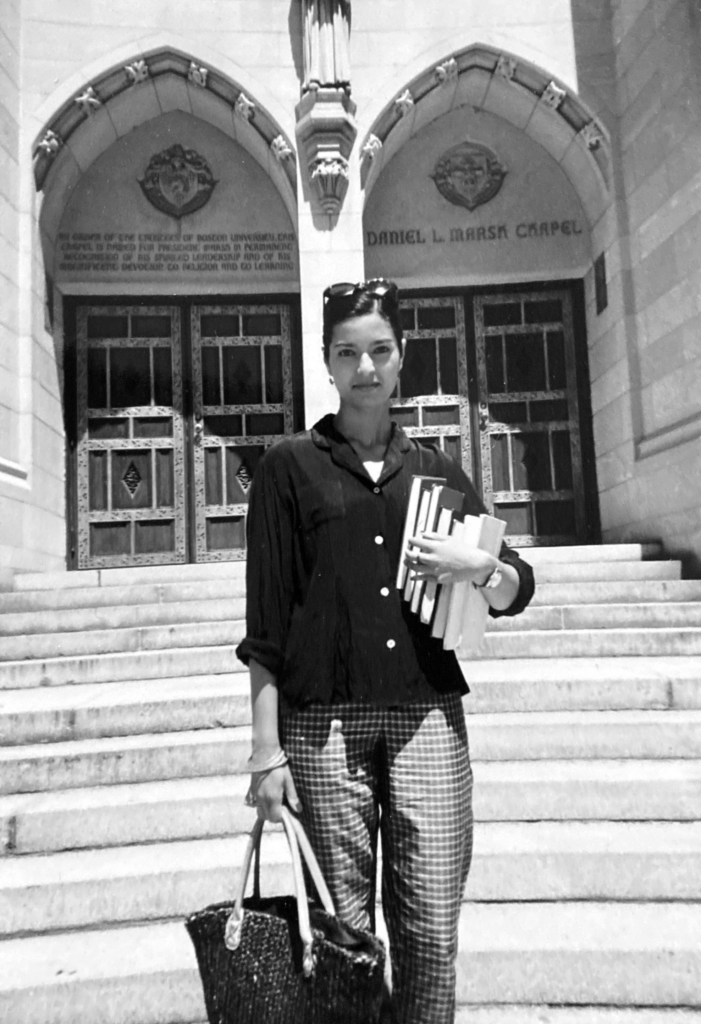

Lahiri at Boston University, where she attended graduate school, in 1997.

“I’ve kept [a journal] for decades—it’s the font of all my writing,” Jhumpa Lahiri told Francesco Pacifico in her Art of Fiction interview, which appears in the new Spring issue of The Paris Review. “That mode, which involves carving out a space in which no one is watching or listening, is how I’ve always operated.” She described a class she recently taught at Barnard on the diary, and we asked her for her syllabus for our ongoing series; hers includes a wide range of texts which all carve out that particular, intimate space.

Course description

What inspires a writer to keep a diary, and how does reading a diary enhance our appreciation of the writer’s creative journey? How do we approach reading texts that were perhaps never intended to be published or read by others? What does keeping a diary teach us about dialogue and description, or about creating character and plot, about narrating the passage of time? How is a diary distinct from autofiction? In this workshop we will evaluate literary diaries—an intrinsically fluid genre—not only as autobiographical commentaries but as incubators of self-knowledge, experimentation, and intimate engagement with other texts. We will also read works in which the diary serves as a narrative device, blurring distinctions between confession and invention, and complicating the relationship between fact and fiction. Readings will serve as inspiration for establishing, appreciating, and cultivating this writerly practice.

Schedule

Week 1: Susan Sontag, Reborn: Diaries and Notebooks, 1947–1963

Week 2: André Gide, Journals and The Counterfeiters

Week 3: Franz Kafka, Diaries, 1910–1923

Week 4: Virginia Woolf, A Writer’s Diary

Week 5: Carolina Maria de Jesus, Child of the Dark

Week 6: Cesare Pavese, The Burning Brand: Diaries 1935–1950

Week 7: Bram Stoker, Dracula

Week 8: Robert Walser, A Schoolboy’s Diary; James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Week 9: Leonora Carrington, Down Below; Primo Levi, “His Own Blacksmith: To Italo Calvino”

Week 10: Annie Ernaux, Happening

Week 11: Lydia Davis, “Cape Cod Diary”; Sarah Manguso, Ongoingness

Week 12: Alba de Céspedes, Forbidden Notebook

Week 13: Alba de Céspedes, Forbidden Notebook

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/KyktDBI

Comments

Post a Comment