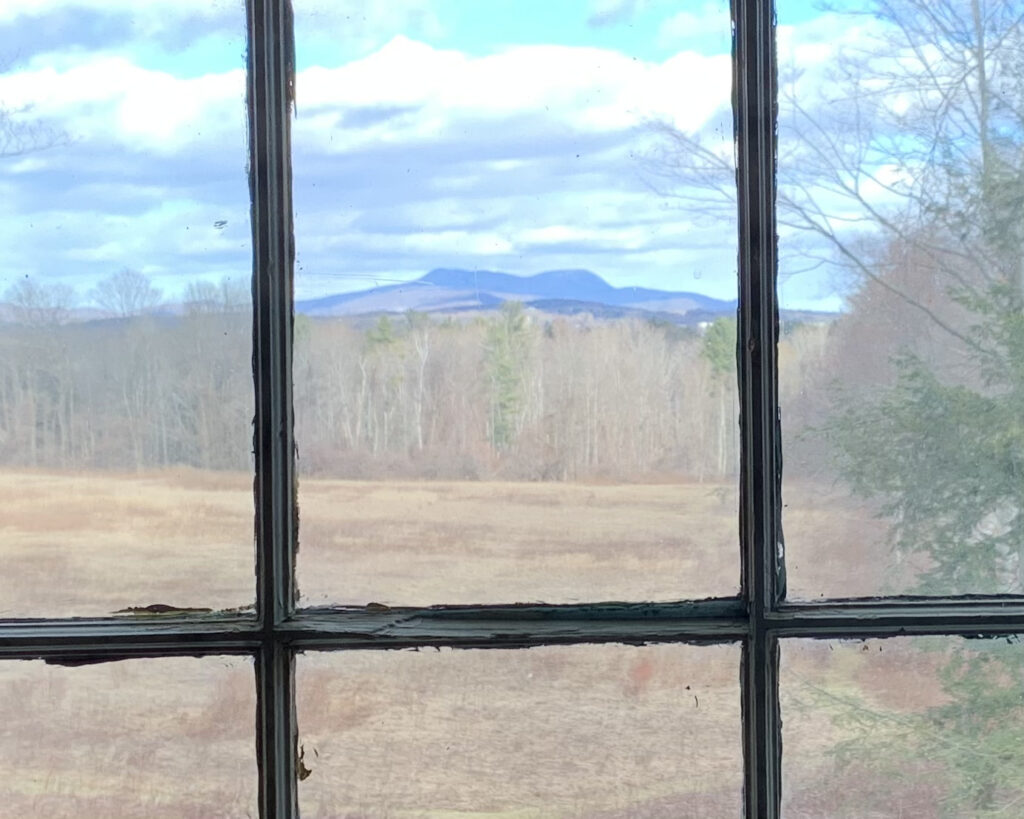

View of Mount Greylock from Herman Melville’s desk in Pittsfield. Licensed under CCO 4.0, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The fictional Pittsfield, Massachusetts, native Mack Bolan first appeared in Don Pendleton’s 1969 novel The Executioner #1: War Against the Mafia. A self-righteous vigilante (“I am not their judge. I am their judgment”), the by-now-lesser-known Bolan was the inspiration for the popular Marvel Comics antihero Frank Castle, also called the Punisher, who made his debut in 1974’s The Amazing Spider-Man #129 and who has been played by Dolph Lundgren, Thomas Jane, and Ray Stevenson in three movies and by Jon Bernthal in a recent Netflix television series. (Season one, episode one: Castle is reading Moby-Dick.)

Bolan’s and Castle’s origins are not the same. Castle’s family was murdered by the mob—that’s how the red wheel cranks into motion, that’s his permission to kill. But Bolan’s story is different. His father gets in debt to the mob, gets sick, and falls behind on loan payments. His sister, Cindy, starts turning tricks for the mob to help pay off her father’s debt. When Bolan’s little brother finds her out, he tells their father. Their father shoots his son, Bolan’s brother, wounding him, then kills his wife and daughter, Bolan’s mother and sister, before killing himself. War Against the Mafia begins with Bolan turning away from the fact that it was his own father, not the mob, who murdered his family.

Given that Bolan was from Pittsfield, where Herman Melville lived from 1850 until 1863, and given that Castle in 2008’s Punisher: War Zone snarls in a church, “I’d like to get my hands on God,” and given that “War Against the Father” could be another name for the satanic Captain Ahab’s pursuit of Moby-Dick as a murderous revolt against God the Father, it was no surprise to me that these overlapping references filled my head as I drove toward Pittsfield through blinding sleet. “You Are At 1724 Feet Highest Elevation on I-90 East of South Dakota,” said a brown sign near Becket, Massachusetts. Hence my elevated thoughts.

I have been to that even more elevated spot on I-90 in South Dakota. The year was 2016. I saw the sun rise as I drove through the Fort Pierre National Grassland on US 83. Then I turned east on I-90 at Vivian, ate breakfast in Presho, and drove through Kennebec and Lyman and Reliance and Oacoma (1,729 feet above sea level, five feet higher than the roadside sign in Becket) and Chamberlain and Pukwana and Kimball and White Lake and Plankinton and Mount Vernon and Betts and Mitchell and Alexandria and Hartford on my way to Sioux Falls, where I stopped at Bob’s Cafe for a dynamite two-piece fried chicken plate with beans and slaw.

I was born in Kentucky and I lived there for thirty years, and I know a thing or two about fried chicken. That chicken was the best thing that happened to me all day in Sioux Falls, better than Second Chance Auto Buy Sell Trade, Appliance and Furniture RentAll, Delux Motel, Paradise Casino, Booze Boys Discount Wine & Liquor, World Wide Automotive, Automatic Super Wash, Specialty Wheel & Tire, Brothers Auto Sales, MetaBank, J.J.’s Billiards, Easy Dough Casino, $$$ Jokerz Casino, Robson Hardware, Freedom Valu Center, West Side City Casino, Angel Nails, J & R Auto Sales, Interstate All Battery Center, or the W. H. Lyon Fairgrounds, and even better than Zort’s Fireworks, five miles northwest of Sioux City on I-29.

There’s not much I like better than driving in this country.

Lighting out for Mack Bolan territory, then, westward leading on I-90 through Natick and Cochituate and Framingham, Fayville and Westborough and Woodville and North Grafton, Charlton City and Fiskdale and West Brimfield, Palmer Center and Thorndike and Three Rivers and East Wilbraham, Ludlow and Springfield and Chicopee and West Springfield and Westfield, Woronoco and Woronoco Heights and Blandford, into Berkshire County and West Becket and East Lee, and north on 20 through Lee and Lenox and the Housatonic Valley to Arrowhead, on the southern outskirts of Pittsfield. Let’s see what Melville has to say about all of this.

Snow in the yards and snow on the roofs of Grafton, snow on the rocks, snow on the hills. A red-tailed hawk crossed left to right in front of my car so low I could see the brown and white marks on her belly. Snow on the banks of the stream at Auburn. Snow on the stonework underneath the power lines. Snow in the wide white fields. Snow falling on Charlton westbound service plaza. Coming into Palmer, the Quaboag River was partly frozen, white with snow. Coming into Wilbraham, Home of [illegible] Ice Cream, its sign was buried under snow. Coming into West Springfield, visibility got low at the Connecticut River. My car was encrusted with dirty road salt like a steak au poivre. I smelled like a french fry. Some of the huge spears of ice hanging from red and brown rock walls to the left and right were netted off, as if to discourage or prevent ice climbing. Made me want to do a bit of front-pointing.

The trucks roared past, dangerous in the wet snow. Home Depot, Rent Me Starting at $29. A cement mixer with J. P. Noonan Transportation flaps. A Herc Rentals flatbed. A J. P. Rivard flatbed out of North Chelmsford. A Ford Super Duty F-350 XLT pulling a trailer with three wrecked cars on it. Arpin America Moving and Storage, operated by Wheaton Van Lines out of Indianapolis.

The bear went over the mountain to see what he could see, but all that he could see was the other side of the mountain. So the bear came down the other side of the mountain, down, down, like Pip in Moby-Dick when he saw the foot upon the treadle—

carried down alive to wondrous depths … and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad.

Andrew Delbanco tells us in Melville: His World and Work that it was during an 1850 hike together up Monument Mountain (elevation 1,642 feet) in Stockbridge, Berkshire County, that Nathaniel Hawthorne stoked Melville’s literary ambition anew, stirring him to revise his existing manuscript of Moby-Dick entirely and to set his sights higher, to proclaim rapturously that “genius, all over the world, stands hand in hand, and one shock of recognition runs the whole circle round.”

Melville meant himself. You want to be careful what you wish for. Inspiration means breathing. Fish breathe by drowning.

And Laurie Robertson-Lorant tells us, in Melville: A Biography, that when Melville moved to Pittsfield in 1850, “the Boston Daily Times picked it up and announced: ‘Herman Melville, the popular young author, has purchased a farm in Berkshire county Mass., about thirty miles from Albany, where he intends to raise poultry, turnips, babies, and other vegetables.’ ”

Here are some of the vegetables Melville managed to raise at Arrowhead. Moby-Dick; or, The Whale.—Pierre; or, The Ambiguities.—Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile.—The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade.

Now see here. I have driven to Arrowhead—a big mustard-yellow house built in the 1780s on 160 acres, a secular shrine, profane, not divine, but genuine, actual, and legitimate—and looked out of Melville’s upstairs-study window at Mount Greylock, that “grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.”

Melville wrote, of this view:

I look out of my window in the morning when I rise as I would out of a port-hole of a ship in the Atlantic. My room seems a ship’s cabin; & at nights when I wake up & hear the wind shrieking, I almost fancy there is too much sail on the house, & I had better go on the roof & rig in the chimney.

It was snowing on the hill as I stood and stared at the white whale’s twin.

The whaling voyage was welcome; the great flood-gates of the wonder-world swung open, and in the wild conceits that swayed me to my purpose, two and two there floated into my inmost soul, endless processions of the whale, and, mid most of them all, one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.

There she blows!—there she blows! A hump like a snow-hill! It is Moby-Dick!

Hot tears are in my eyes, the same eyes that saw the white whale, as I write this. Where today are the castaways of my youth, the rednecks of Fern Creek and Okolona and Fairdale and J-Town and Buechel and Newburg who loved Moby-Dick as only fundamentalists, trained to treat a book as holy, can love a make-believe story?

I can still hear Ronnie’s friend Dopey Mike howling “Thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee!” Dopey Mike was a bore, a dangerous bore. I never saw that dopey alchemist again after he spilled his wormwood-stinking homemade absinthe apparatus, alembics and all, and set Ronnie’s kitchen on fire. That was at Ronnie’s house down by the Moby Dick restaurant at South Third and Winkler, come to think of it. My ex-wife loved their breaded mushrooms. She hated their hush puppies, though. Back then I was a loud puppy. You don’t see a lot of alembics these days. Ronnie himself is a fugitive from justice, that’s the news from back home. Why then here does anyone step forth?—Because one did survive the wreck.

It’s no secret that Melville loved his big porch at Arrowhead.

When I removed into the country, it was to occupy an old-fashioned farm-house, which had no piazza … Now, for a house, so situated in such a country, to have no piazza for the convenience of those who might desire to feast upon the view, and take their time and ease about it, seemed as much of an omission as if a picture-gallery should have no bench … A piazza must be had. The house was wide—my fortune narrow; so that, to build a panoramic piazza, one round and round, it could not be … Upon but one of the four sides would prudence grant me what I wanted. Now, which side? … No sooner was ground broken, than all the neighborhood, neighbor Dives, in particular, broke, too—into a laugh. Piazza to the north! Winter piazza! … But, even in December, this northern piazza does not repel—nipping cold and gusty though it be, and the north wind, like any miller, bolting by the snow, in finest flour—for then, once more, with frosted beard, I pace the sleety deck, weathering Cape Horn.

Melville wrote a book about his porch, The Piazza Tales. That’s where you’ll find “Benito Cereno” and “Bartleby, the Scrivener.” I and the other pilgrims to Arrowhead stood on the sleety deck of Melville’s yellow winter piazza not in December but in February, still nipping cold and gusty, snow lashing our faces as we gazed across pale brown fields.

The true believers were nowhere in sight on that snowy morning. Our guide had a few questions. “Do you know a lot about Melville?” he said to me. “I had a real big fan here one time. Showed me up. Told me later he taught Melville at Michigan.”

“I just read the make-believe stories. I don’t know anything about the real man.” Which is not true. I munched on that Elizabeth Hardwick biography of Melville back in 2000. But what are you, the cops? Show me your badge.

A tall, good-looking man with a closely trimmed white beard wearing under his winter coat a black T-shirt with a picture of Bender, the robot from Futurama, said, “I don’t even know who Herman Melville is. I’ll be honest with you, I’m not sure why I’m here today.” Not one man jack of them had read Moby-Dick. Still, they had been drawn there by a mysterious force.

Our guide wasn’t a fan. He finished the tour and said, “Before we disperse, can we all agree that Moby-Dick is a hot mess?” It was a strange question to ask a roomful of people who had already admitted they hadn’t read the book. The heretics are in charge of this temple, I thought, but their devotion is more poignant because they do not believe. They do not have faith, but they have faith in faith.

I mostly managed to keep my mouth shut, which is not my strong suit. But as our guide rambled on about how he thought Moby-Dick should have been cut by half, such that it was only the exciting fish story shorn of whaling arcana, my evil spirit came upon me and opened my jaws. The part you hate is my favorite part, I said. He stared at me as if I were a madman. Which, of course, I am. But I saw the whale first. The doubloon is mine.

J. D. Daniels is the winner of a 2016 Whiting Award and The Paris Review’s 2013 Terry Southern Prize. His collection The Correspondence was published in 2017. His writing has appeared in The Paris Review, Esquire, n+1, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere, including The Best American Essays and The Best American Travel Writing.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/l9DVZo1

Comments

Post a Comment