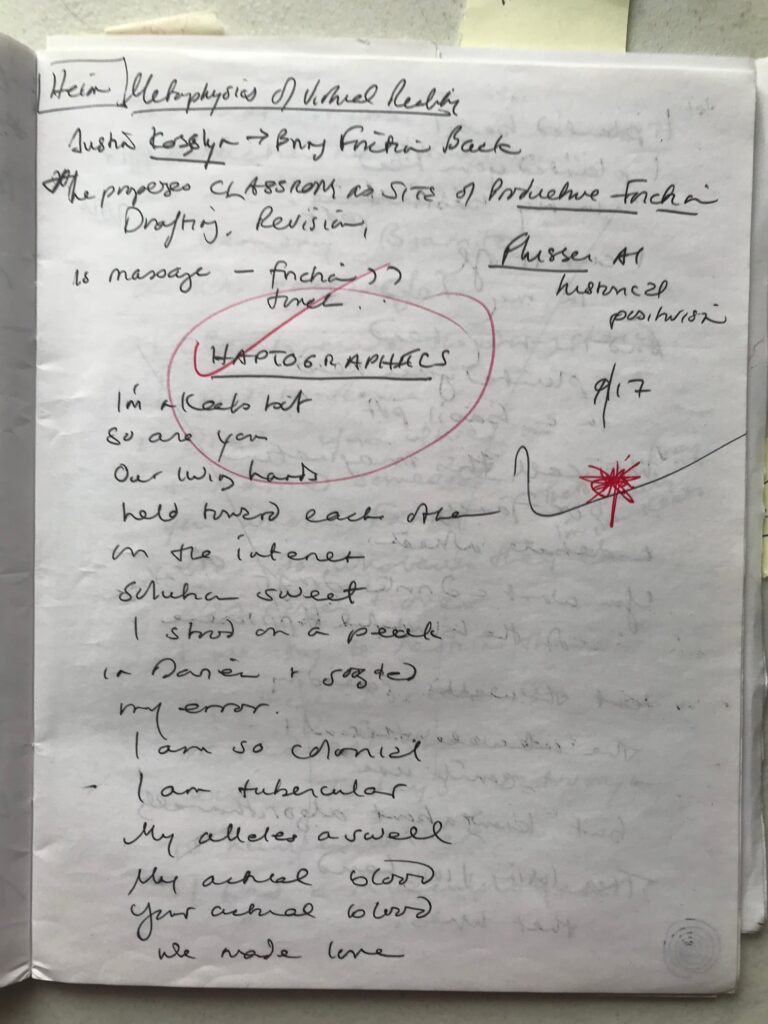

The poem begins. Photograph courtesy of Maureen McLane.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Maureen N. McLane’s poem “Haptographic Interface” appears in the new Spring issue of the Review.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

This poem took wing, or distilled itself, during a conference on “Writing Practice” at Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf in September 2022. I started writing while listening to the closing remarks. The scholar Andrew Bennett had given a talk on Keats vis-à-vis haptographics, a term I hadn’t heard before—that was one spur. Keats is someone I’ve read and thought about for a long time (in one wing of my life I work on Romantic-era poetry). Bennett had spoken about Keats’s handwriting—how moving it can be to encounter it—and his letters, and the matter of “literary remains.” Some months after the conference, I looked up haptographics—one of the first hits on Google tells you that “haptographic technology involves highly sensorized handheld tools”—is a pen such? Haptography is a technique for “capturing the feel of real objects”—is this what Keats was up to, capturing the feel of things (experiences, emotions, movements of thought)? I think so. Is this still poetry’s aim? These are questions the poem implicitly pursues, but I can only say that having written the poem. There was no thesis-in-advance.

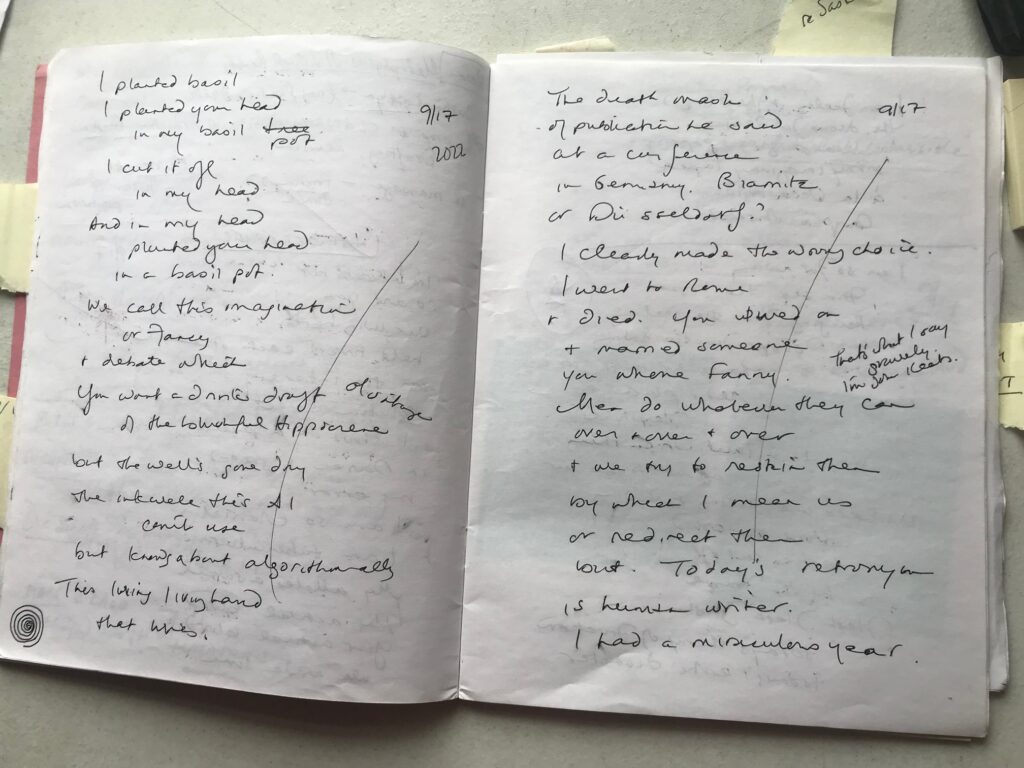

At the conference, I was intermittently taking notes and making notes while others were talking. Having a pen in my hand probably spurred that kind of dreamlike composition. The conference raised questions about writing, mediation, materiality, of the intersections between technology and art, of the sensorium. The human sensorium is key Keatsian terrain, and he is preoccupied too with poetic ambition. Other things in the mix included ambient concerns about AI. During the conference, one scholar invoked the term human writers, about which I noted in my notebook, “oy retronym.” A lot of floating things were concretized in the drafting.

Notebook pages. Photograph courtesy of Maureen McLane.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult to write? (Are there hard and easy poems?)

It was quite easy to write, a kind of channeling—I was probably usefully disinhibited, doing this while also listening, a kind of parallel play … or lyric dispossession.

Who is the speaker of this poem?

I guess you could say that the speaker of the poem emerges en route as “John Keats”—some amalgam of the figure of Keats, a kind of AI Keats, and me. So there’s an “I” generated out of some weird processing of “John Keats”—as poet, historical figure, representative case of and for poetry, persona/mask. The speaker is a kind of Keats-bot, perhaps. Our bots, ourselves.

How did you come up with the title for this poem?

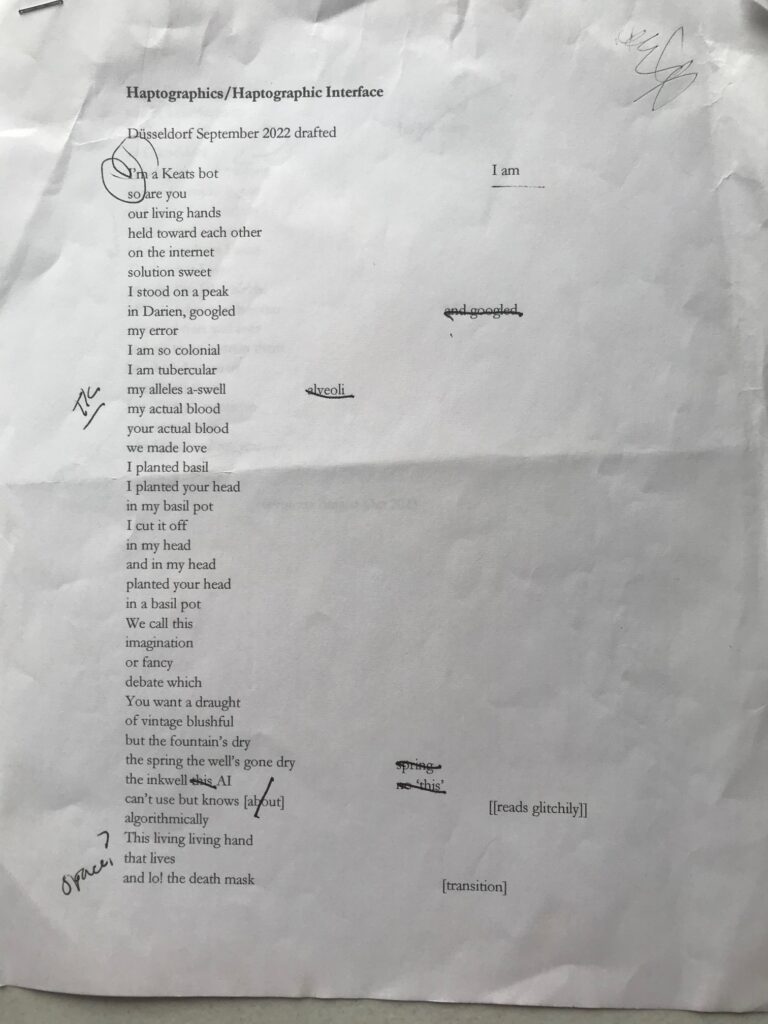

I was drawing on the title of Bennett’s talk, and my poem title was first “Haptographics,” as you see in the notebook, but ultimately became “Haptographic Interface.” I hovered for a while between the two, but the bot poet / poet-as-bot ultimately seemed to be an interface, and that seemed central to the poem.

A printed revision of the poem. Photograph courtesy of Maureen McLane.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

I don’t know that I was thinking of anything, per se. Things came to mind and popped up organically—or robotically!—as I was writing, including Keats’s “Isabella, or the Pot of Basil,” and his sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” where he invokes a “peak in Darien.” “Isabella” is a very strange, creepy-sexy gothic neomedieval poem, and it probably occurred to me because I was working with a kind of creepy “John Keats” figure, and maybe because another conference-goer had mentioned the poem. To be honest, a lot of Keats can spontaneously bubble up for me—key phrases and lines. So too, motifs from romantic literature, including debates about fancy versus imagination—Coleridge is crucial for that.

My poem is in part a tissue of quotation and a kind of weird channeling of those Keatsian motifs. In this way, the poem navigates between the logic of AI—which presumes a massive devouring and sifting of existing databases—and more local or traditional instances of poetic composition, what Susan Stewart has called lyric possession, or Derrida, in another key, has called hauntology. A Keats-bot brings its own hauntings with it.

Also in the hinterland of my mind may have been two great recent books by critics—Anahid Nersessian’s Keats’s Odes: A Lover’s Discourse and Erica McAlpine’s The Poet’s Mistake. Nersessian’s book gives us a deeply lovable, charismatic, politically progressive, and brilliantly sensual Keats. Keats’s biography haunts the poem in various ways—his frustrated love for Fanny Brawne, his incredibly rapid development as a poet in his early twenties, his terrible early death in Rome from tuberculosis. The Keats-bot figure of the poem is partially that biographical Keats and partially a furious or alienated posthumous Keats, which he could also be, despite general hagiography. McAlpine has a great reading of “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” which famously features a mistake, placing the conquistador Cortez upon that “peak in Darien,” gazing at the Pacific with a wonder analogous to Keats’s on first reading George Chapman’s translation of Homer. As McAlpine notes, it was Balboa, not Cortez, who first looked at the Pacific from the isthmus of Darien. Now we’re really in the weeds, but McAlpine’s exploration of poetic intentionality and error points to the challenges raised by a Keats-bot—what accounts of poetic intention or poetic making are plausible for us, at this juncture? What versions of poetry are obsolete—and are “human writers” obsolete? The poem circles and does not answer these questions.

Maureen N. McLane’s most recent book is the essay collection My Poetics.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/oSsFxn0

Comments

Post a Comment