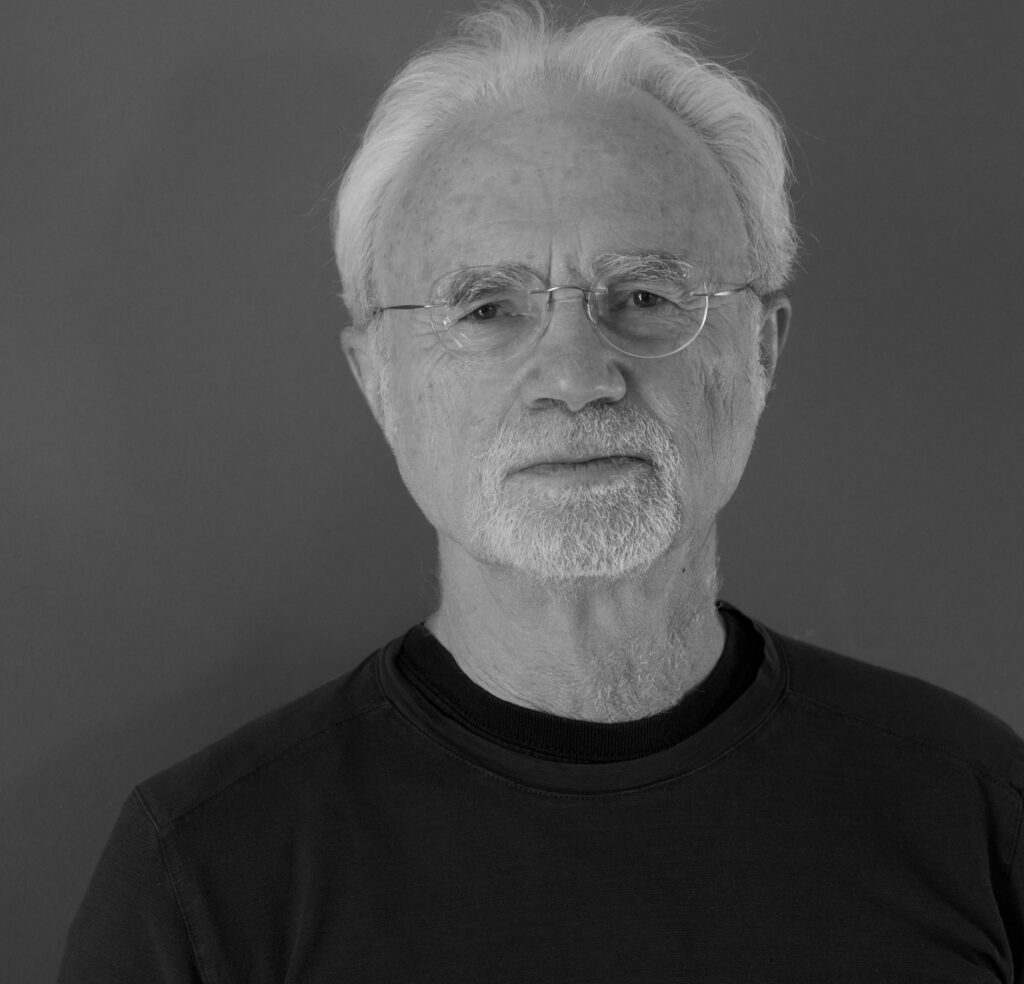

John Adams. Photograph by Deborah O’Grady.

This week, a new production of the composer John Adams’s oratorio El Niño opened at the Metropolitan Opera, where it will run until May 17. El Niño is Adams’ rewriting of the Nativity story, and his libretto—cowritten with stage director Peter Sellars, in one their many collaborations—draws on source texts as wide-ranging the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and Mexican poetry written in the sixties. The text of the libretto reminded me of an assemblage poem as much as an opera. I spoke to Adams, who has composed some of the most notable contemporary operas, among them Nixon in China, for our Art of The Libretto series. We talked over Zoom recently about the joys and pains of collaboration, learning and then setting Spanish text to music, his life as a Californian, and his attempt to write his own Messiah.

INTERVIEWER

How did El Niño begin for you?

JOHN ADAMS

I’d been asked by the Châtelet in Paris to create something to celebrate for the millennium. So I began to think about what the millennium was and what was special about the year 2000. It also reminded me that ever since I was a kid, I had always loved Handel’s Messiah, which speaks to that time of year, because it’s also about birth, optimism, and hope. I thought that the millennium as a celebration should have something to do with these emotions. If you want to put it in another way, I wanted to write my own Messiah.

INTERVIEWER

I’m curious about your collaboration with Peter Sellars on the libretto for El Niño. I know you collaborated on operas and other stage works over a period of thirty years, but in this instance, what did that exchange look like?

ADAMS

In this case, we had the framework of the Nativity story, so we didn’t have to worry a great deal about devising a new narrative structure. But what Peter did, which gave the piece its unique flavor, was to suggest a selection of texts, many of which came from the Hispanic poetic tradition. I confess that I was largely untutored in most of that poetry, so I was very grateful to him for turning things in that direction. Over a period of several months, we met several times with piles and piles of books and sketched out what I call a flowchart. Some of the texts I contributed, too. The anonymous early English poem that opens the score—I had seen that, believe it or not, in the London Underground. It’s just wonderful to think that the London Underground would have poetry alongside all the ads for patent medicine and West End shows. So that lovely poem, “I Sing a Maiden,” stayed in my mind’s eye and beautifully set the tone for opening the piece. I also wanted to include the Martin Luther text that describes the misery of Mary and Joseph trying to find a place to stay in Bethlehem. It was Peter’s idea to draw from the Apocrypha, an imaginative touch that imparts a certain feeling of innocence, especially to the end, because these stories are really like children’s stories. And because it’s more an oratorio than an opera I felt a kind of dramatic liberty to move back and forth through time, having the prophet Isaiah from the Old Testament, and then something as almost shockingly contemporary as the Rosario Castellanos poem “Memorial de Tlatelolco,” which serves here as the Massacre of the Innocents in our narrative.

INTERVIEWER

How did you gravitate toward the poetry of Rosario Castellanos, and how do those poems work within the larger text?

ADAMS

There are two big Castellanos poems that function as the major pivots in parts one and two. The first is “La anunciación,” a portion of a much longer poem by Castellanos, which is fundamentally telling a creation scenario. She evokes a scenario before recorded time in a way that to me suggests something from Einstein’s theory on space and time. She’s also apostrophizing her son, and the poem has extraordinary imagery in it—of the pregnancy and the pain and ecstasy of giving birth. I responded to that poem so strongly because not long before I wrote this our two children were born, and I was there, witnessing the moment of birth. Then, in part two, the Castellanos poem “Memorial de Tlatelolco” is one of bitter irony that addresses the absolute polar end of the spectrum of human violence and the murder of young people.

INTERVIEWER

How did you think about the mixture of languages in this libretto, and moving back and forth between English and Spanish?

ADAMS

I did not speak Spanish when I agreed to do this, but I began learning Spanish—in a hurry! Now when I go back to El Niño, I see a couple of misjudgments in my setting of some words, where I put a stress on the wrong syllable, but I found setting music to Spanish to be a wonderful experience. So in several other later pieces, like The Gospel According to the Other Mary and my more recent Gold Rush opera, Girls of the Golden West, I set quite a few texts in Spanish. I think that’s partly a response to my life as a Californian. We’re almost a bilingual state, and I was ashamed of myself that I’d lived here for so long without learning the language. And I respond very strongly to the sound of the words, to the shape of a phrase, when I’m composing.

INTERVIEWER

In general, how does it feel to collaborate when you’re setting text to music?

ADAMS

I once said that I thought that the two most painful things two human beings can do together are a double-ax murder or an artistic collaboration. It’s difficult, particularly with a librettist. My first operas had brilliant libretti by Alice Goodman. I think that the libretti in Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer are among the greatest libretti of all operas, but the process was very difficult. It was painful because each of us—composer and librettist—brings to the table one’s very best, but in the end a work of musical theater has to obey both the dramatic form dictated by the music. Once I start composing, I have to mostly take over the steering wheel, because the success of a dramatic work really depends on the musical flow. Unfortunately, it’s the composer who often ends up having to make the formal decisions about what has to be cut. It’s possible to have a very passive librettist who says, “Sure, go ahead.” But usually—and certainly with Alice—it was very difficult for her to see what she felt was some of her best work end up on the cutting-room floor, so to speak.

INTERVIEWER

What was the revision process like in the case of El Niño?

ADAMS

I don’t really recall having any basic struggle with El Niño, nor do I recall having to make any substantial revisions to it—unlike many of my other operas, where after the first or second productions, I’ve had to go back and make cuts or revisions. During the pandemic, I read several biographies of Verdi, and one of the things that struck me was how much of his adult life he spent revising his operas. Given how many operas he wrote, that’s kind of astonishing, but that’s the nature of opera. It has all the problems that a play would have, and then it has all the problems that a piece of music would have, so your chances of getting something that’s absolutely perfect are very slender. I even think of The Marriage of Figaro, which of course is one of the great operas, but for me, it’s too long. Even the greatest composers sometimes can make mistakes on a dramatic level.

INTERVIEWER

Something noticeable about El Niño is how much joy there is in the libretto, which strikes me as rare in opera. How did you think about joy when you were composing this opera, and how do you think about it in your work in general?

ADAMS

As I mentioned, I had the image of the birth of our own children in mind, and I had the same feeling that you do, that so much of not just opera but of so much art in the Western world is very grim and pessimistic now. So many composers are addressing matters that they feel very deeply about, which are also all the dour things that we read about on the New York Times editorial page and the dark clouds we live under. All this work is important, but I wanted to look at these texts and to contemplate birth and rebirth, and to think about how music can truly lift the spirit. I don’t have many pieces that are really emotionally down. The Death of Klinghoffer of course and its general affect is tragic, but not pessimistic. But I guess you could say I’m fundamentally some form of Emersonian American optimist in that I’m really trying to use music to lift the spirit. El Niño for sure is the clearest example of that.

The Metropolitan Opera’s new production of El Niño is directed by Lileana Blain-Cruz and stars Julia Bullock, J’Nai Bridges, and Davóne Tines. Tickets and schedule can be found here.

Sophie Haigney is the web editor of The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/S7P98f6

Comments

Post a Comment