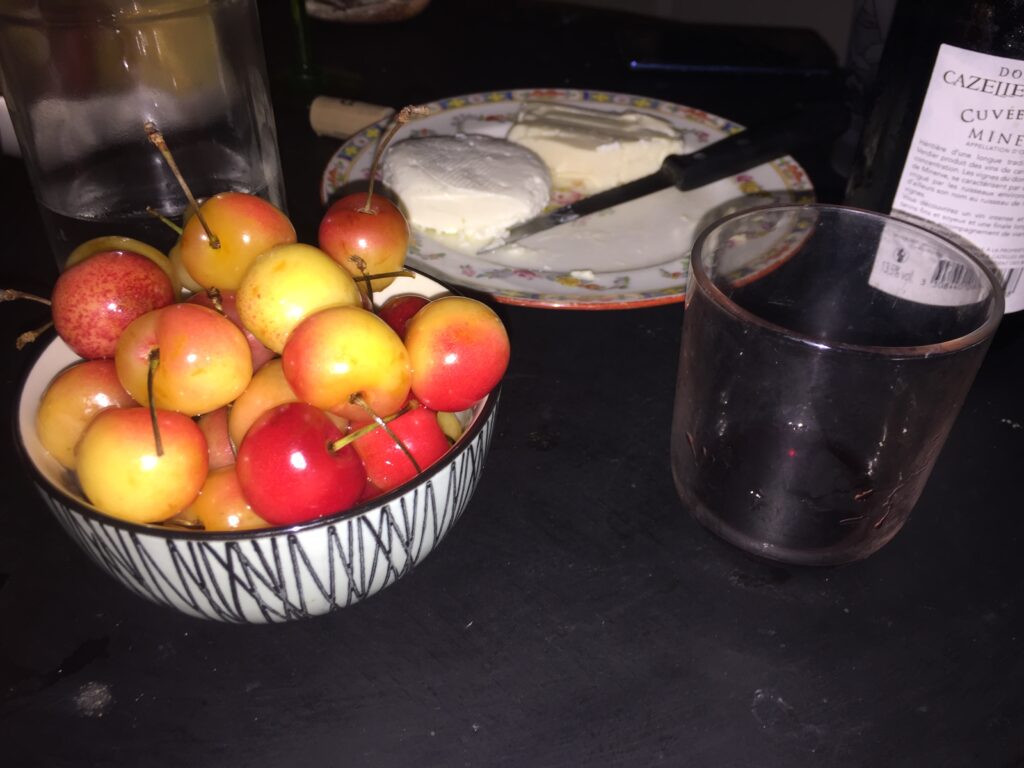

Photograph by Jacqueline Feldman.

There had been concern when Jean and Emma got together that he was too serious, macho. I perhaps had it wrong that he had in art school driven to Chernobyl, uprooted a tree, and brought it back to France—a foreigner, I was capable of wild misunderstandings—but this was the story that had come to seem defining. Now he made a dance out of crumpling a wrapper, hopping up to throw it in the trash. He snapped his fingers to the music. It was cheerful music, music from my country though not from my era. In a city famous for ways of living developed, cultivated to exquisiteness, over centuries, we were engaged, that night, in a rare shabby tradition, that of the apéro dînatoire. Emma was throwing one ahead of moving in with Jean.

Possibly the tradition was not exclusively Parisian. “They do it systematically in Greece,” Jean said.

On a cutting board were resting chocolate bread from Chambelland, a slab of Comté, a “beautiful” radish Jean had brought, and chips: “I have chips because you said there must be chips for the feuilleton,” Emma said to me, referring to my plan to write about the evening. Having touched down that morning I was making such demands on top of being welcomed back. Stefania, who came late, brought sticks of crabmeat, olives, and a two-liter bottle of Coke.

Stefania was “a musician and artiste d’art vivant,” Emma said.

“Easier,” said Stefania, “I’d say artiste sonore, performeuse.” Romanian, she had been living in Paris for four years and liked it, though her own apartment was, like Emma’s, too small. “That’s the toilet?” she asked.

“It’s not very far from us,” Jean commented.

“Sorry,” Stefania said, “but I have need. Put the music back on.”

Emma’s boxes were piled two high on a bed she called “the sofa” and Jean called “the divan.” Plants remained unpacked and cast exaggerated shadows. She had done such a good job, remarked Haydée. “C’est vraiment très bien rangé.”

A mover, Patrice, would be there tomorrow. “He is an artist,” said Emma, “and his art is to sleep in his car.”

“He has to find a place to shower every day,” Jean said, reframing.

There would be furniture already, the apartment would be new to both of them, the furniture too heavy to get rid of. There was a table that Emma thought they might use a tablecloth on. Haydée accepted Emma’s phone to see a photo. “Oh but it’s fine,” she said. “It’s very good, Emma. But the chairs, you took them away?”

There would be, the next day, a great duty of transferring boxes, which I, arriving in the group’s life always just in time to catch the end of something, had been excused from (the mover, Patrice, who had a bad back, would drive).

Emma, as I raced to get down what she said , wished that she could have a note taker for all of her soirées. Haydée thought the company could stand to get a little bit more novelesque. “We should invent characters,” she said.

Raphaël called, as if freshly invented—but he was a high school friend of Emma’s, and someone who had been helpful lately, with the lease. His voice came through the stereo in the place of music.

“Ah,” said Haydée, “your guarantor!”

“My guarantor is coming!” Emma said.

“Emma is supposed to be his mistress,” Jean said to me, disgusted with the system that had left him off this document.

Raphaël, when he arrived, asked Emma if she didn’t feel nostalgic. She did, and this meant she had been wanting, for some minutes, to fill every corner of the space awaiting disuse with our movement. She wanted us to sing. “Il faut passer à l’action,” said Stefania. Raphaël made suggestions Jean found ridiculous. “Dylan,” scoffed Jean, “Brassens, ça fait rire.” They “made” him “laugh” in a bad way. But Raphaël was taking lessons, singing lessons. Here he offered up a song in Spanish. I taped some of all of this later to play it loud, its overlay the well- or ill-timed interruptive rustle, flaws by then like a mutation taken in my absence, not exactly like this.

My first day back even the weather was suggestive of a possibility, not only the necessity, of remaining present while in transit, while the flow goes on around you. Stasis, not activity, was the delusion. As signs read—outside, around the city—“TERRACE OPEN.” Trees that smelled bad were in flower, the canal was brackish, I lingered mesmerized by tulips out front of a Franprix. A woman called back to her son. I heard the question clearly. “Do you want hot chocolate,” she asked, “or lemonade?”

Reaching Emma’s building just as she was getting home I’d praised her for throwing a party at all. Packing took me up until the very last moment, always. “I remember,” Emma said, referring to a summer night when I’d stuck her with old clothes; we’d taken boxes of my notes to store at Hugo’s, her high school friend who’d introduced us. “It’s boxes,” she cautioned now, a nicety, as we climbed the curving stairs. “J’ai l’habitude,” I of course said in reply.

Jean, third to arrive, had not long after emerged rather suddenly, flushed and unkempt, from Emma’s bedroom, where he had been apparently only pretending to nap. He was “interested” in stories I was telling, he said to Emma and me, in a tone of apology, “as we only hear them episodically. It’s interesting.”

Jacqueline Feldman’s On Your Feet, a bilingual experiment, was published in March by dispersed holdings. Precarious Lease, an account of a Parisian squat, is forthcoming from Rescue Press this fall.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/fEt5SGv

Comments

Post a Comment