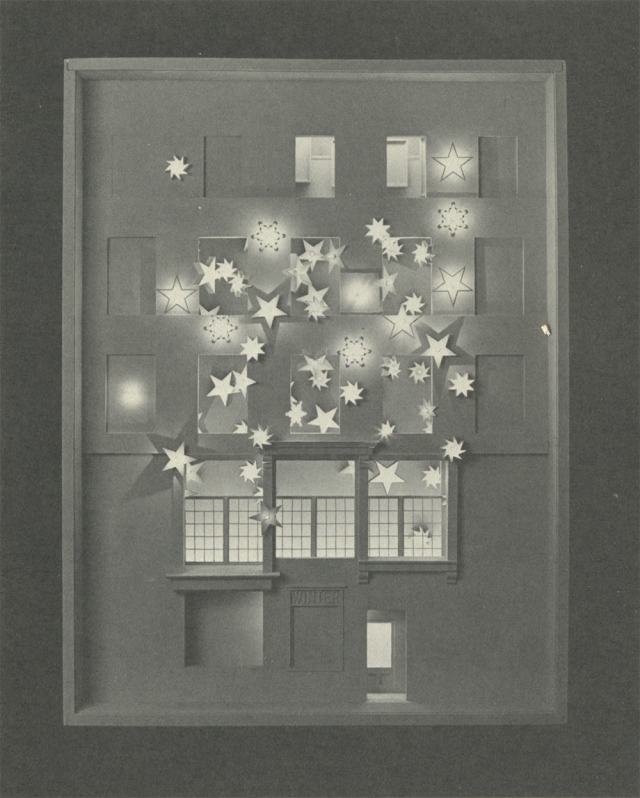

From Cletus Johnson’s Details from “Winter,” a portfolio published in issue no. 68 of The Paris Review (Winter 1978).

Marga was still living where she’d been at the time I’d left New Orleans, in a house shared with friends. On the first floor were Marga and her roommates, who I knew a little, though she continued to introduce us to one another. On the second floor lived more friends, and a piano, which one of them played sometimes, and which Marga and I could hear when we lay in her bed. It was February, I was visiting, and the city smelled of sweet olive, damp soil, and sometimes sweat. At sunset the light was as obscene as I’d remembered it, fluorescent oranges and pinks that someone once told me were so bright because of the chemical pollution. I had spent the week going on walks through the tall grass of the old golf course with people I hadn’t seen since I’d lived there, a span of a few years in which I had felt sometimes elated, often unhappy. I wasn’t unhappy anymore, which made things look and feel different, and made me wonder what it would be to come back more permanently, and who I could be then: if she would be a better version, or at least a version more able to appreciate her time.

It was a work trip. I spent my first night with Marga, as planned, but then I moved to a hotel for a few days following a COVID exposure. My negative test on Friday allowed me back into Marga’s in time for the Shabbat dinner she wanted to host while I was in town, which was going to include us, Marga’s roommates, and a couple I’d asked Marga to invite, plus their dog. When the couple walked in, one half sat down and said to me, “It must feel so good to come back here and have a family waiting for you.” I was surprised, because I hadn’t really felt like that was true, but hearing her say it made me wonder if it was true: if I had left something behind that I hadn’t really realized I’d had, or if somehow in my absence it had thickened into something more real than what I had lived.

Along with the people I knew was one person I didn’t, whom one roommate was dating. He brought a wooden knife that he had made. We all said “Wow,” but it couldn’t even cut the chicken Marga had made, which was very soft; the chicken was not the problem. Marga was proud of what she served us, the chicken but also potatoes, chopped herbs, and a sauce—mostly I remember that it was salty, and that Marga’s pride was both obvious and deserved. I was happy to see her glowing over candles, bragging about food that was good. We talked about a lot of things, and drank wine, and lost ends of conversations that someone else later picked up: their gardens, my work, family, family elsewhere. Talking was easier than I had remembered. Between us, the night felt quiet and warm, with laughter and overlap, small circles of conversation that grew and shrank, and the sense that people were comfortable, glad to be there, and used to it. I felt that maybe this was mundane for them, though it was special for me, and this was its own sweetness, too—that here they all lived with something special, even if it was routine. The fact that it was common didn’t mean that they valued it any less.

When everyone left, I guess we cleaned; it’s possible we didn’t. I was a little drunk, a little high. Marga gave me a toothbrush and a T-shirt and together we washed our faces at the little sink in her bathroom, which had a window out to the backyard, the bugs and the flowers. In bed, she shifted herself back toward me so that I was cupped around her. It was different from how I lay down with my friends from college, but my friends in New Orleans were different from my friends from college, so I let it be. I felt that my perception had slowed down to a half step behind what was happening, so I kept realizing and rerealizing what we were doing: when she touched my leg, and I touched her back, and we kissed, I kept thinking, Oh, Marga and I are having sex now; we’re still having sex; we’re having sex now. Each time I was surprised, and then I’d ask myself, Do I want to keep going? Each time, the answer was yes.

In the morning we got coffee and breakfast tacos and ate by the bayou, then came back to her bed because she needed to study. I had The Well of Loneliness with me but was embarrassed for her to see, because it said “A 1920s Classic of Lesbian Fiction” on the cover and here I was, in bed with my lesbian friend, and we had just had sex. Only so recently she had laughed, surprised, on FaceTime, when I’d told her about my new girlfriend, my first. She had said, “We love gay Devon!” and then “I always knew it,” and “There were all these times when I was like, Is Devon flirting with me?” I had laughed, at the time, and I wondered now if it was true: if everyone here had known things about me I hadn’t yet known, and if I really was so legible.

Later, Marga and I each had somewhere to be. She drove me where I was going, and in the car, looking through the windshield, she asked how I felt about us having sex, which we’d done again that afternoon or morning. She said, “Seeing as we’re old friends.” I said I thought it was probably fine, and she said she did, too. It was. Mostly on her face I saw delight, and when we talk to each other now, or see each other, I see delight sometimes again, and feel it, too, and pleasure that her world exists there without me; that I get to visit it sometimes, and exist in it via invitation.

Devon Brody is a writer living in Nashville.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/48QP0Hy

Comments

Post a Comment