As we were putting together this Summer issue of the Review, an editor in London sent me Saskia Vogel’s new translation of a 1989 book by Peter Cornell, a Swedish historian and art critic. The Ways of Paradise is presented as notes to a scholarly manuscript; the author, Cornell tells us in an introduction, was “a familiar figure at the National Library of Sweden,” where for more than three decades he was “occupied with an uncommonly comprehensive project, a work that—as he once disclosed in confidence—would reveal a chain of connections until then overlooked.” After his death, the manuscript was never found. “Which is to say,” Cornell writes, “all that remains of his great work is its critical apparatus.”

The footnotes that comprise The Ways of Paradise orbit certain preoccupations: the center of the world, labyrinths, flânerie, rock formations, Freudian repression, passwords, folds of fabric, aimlessness. As I followed the trails left behind by the mysterious man Cornell calls the author, I felt an emerging sense of relation between only tangentially related things. (I also felt a relief that the categories of “Fiction” and “Nonfiction” had already been banished from the Review’s table of contents in favor of the more-encompassing “Prose.”)

Taking note of connections, intended or not, is one of the pleasures of deep, patient reading—which is to say, one of the pleasures of reading for pleasure. And so I am always delighted when, despite our best efforts to avoid organizing an issue of the Review around a given idea or theme, a reader will point out that the most recent one was clearly all about this subject or was wrestling with that idea.

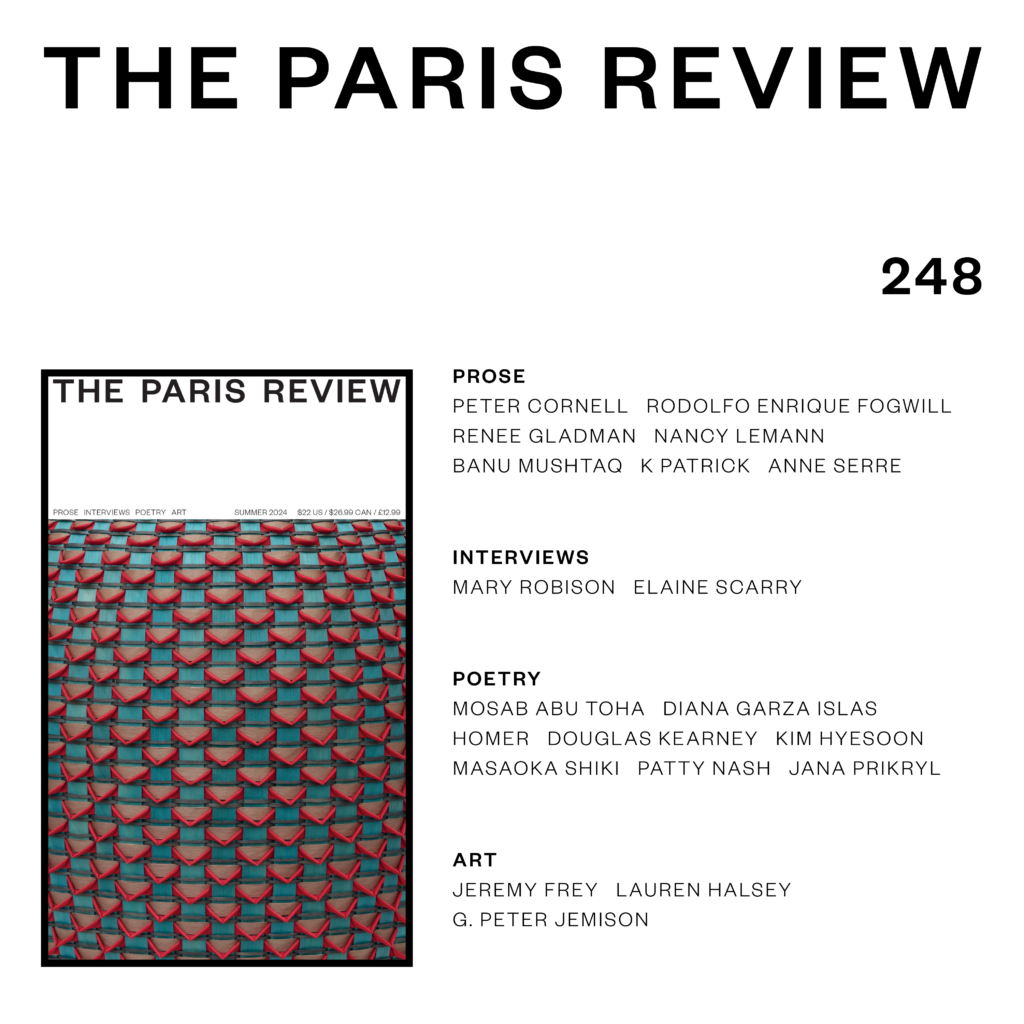

Which makes the kind of letter I am now writing—to announce our new Summer issue, out this week—a conundrum. I could flag its seasonal topicality (“That summer we had decided we were past caring,” Anne Serre writes in the issue’s first story. “It was just too tiring, rushing back and forth between mental institutions”). Or I could, like a savvy host at a drinks party, point out possible conversation starters: works in translation, maybe. Or romance novels (“I am a sucker for women carrying each other around,” Renee Gladman writes in “My Lesbian Novel”). Or the visionary (“It could be a dog crossing the street one morning with a string of wieners, which is something I’ve always wanted to see,” Mary Robison tells Rebecca Bengal in her Art of Fiction interview. “That’s my golden dream”).

But most of the time when we read, we are enjoying something we can’t necessarily name in advance. In Dreaming by the Book (1999), Elaine Scarry argues that when writers describe something, what they’re really doing is instructing the reader in how to make mental images—ones that appear “not just like a lazy daydream,” Scarry explains to Margaret Ross in her Art of Nonfiction interview, “but as an incredibly complex landscape of interactions.” There is no replacement for this powerful exercise, she says: “If you really want to take down someone’s, or a whole population’s, ability to think, you must do it by shutting down their practice of the fictional as well as their practice of the factual.”

Consider this issue of the Review, then, a chain of connections whose links are you, their reader. Soldiers, reportedly killed in combat, disembarking from a train in the eerie light of dawn, in a story by the late Argentine author Rodolfo Enrique Fogwill, translated by Will Vanderhyden. Odysseus sitting on the rocks by the edge of the sea, grieving his homecoming, in Daniel Mendelsohn’s new translation of The Odyssey. Scarry recalling how, as a child on summer vacation, each day she would await her grandfather’s return from the anthracite mines where he worked. “I would trace his path in the dirt over and over,” she says. “I’d think, Now he’s coming out of the mines, now he’s approaching me, when I look up he’s going to be there. No, he’s not there. He’s coming out of the mines, he’s approaching me. No, he’s not there.”

Emily Stokes is the editor of The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/xBWjlqN

Comments

Post a Comment