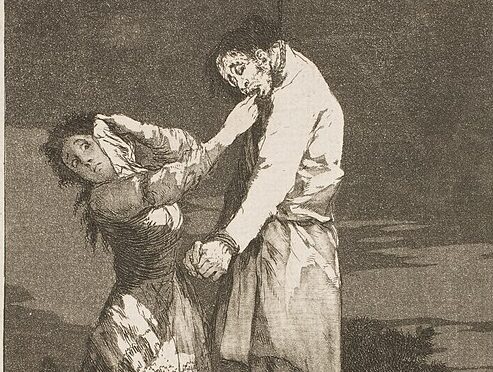

Francisco de Goya, “Out Hunting for Teeth,” 1799. Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

I named her Holy Jemima when I was nine, or thereabouts. I liked the way the words sounded and it was meant cruelly. Holy Jemima was two years older than me, and her family—her mother, father, two sisters, and brother, making six—were in a cult.

I did not know they were in a cult. I just thought they were crazy Christians. The turbo type. I was forced, occasionally, to interact with Holy Jemima, because her little sister, Jessica, was friends with mine.

The whole family had this shark-eyed stare. Holy Jemima would fix me with it and tell me that Harry Potter was evil, that they did not celebrate Halloween in their house because of Satan, and that the school church was getting it all badly wrong.

“You’ve got to come over,” she told me once, “and watch these videos. You have no idea about the world. The school is not telling you about the real miracles that are happening. There is a preacher in Africa, a Black guy, and he is curing people. His name is TB Joshua.”

“You watch videos of church?”

“He has cured AIDS. On video. Exorcisms too. Have you ever seen a demon leave someone’s body? They go like this.” She rolled her eyes back in her head and waved her arms about as if having a seizure and started going aghnaghnahgnghgnghgnhgnhgn.

A thing about growing up: you do not know what is strange until after. This was suburban England and the Holy Jemima’s hobby seemed about the same, to me, as my parents’ doctor friends’ African masks mounted on the walls above their CD towers of world music. Six streets down from them was Bellybutton Man, whose hobby was watching us leave school whilst silently smiling and lifting his blue T-shirt to finger his navel. And Bellybutton Man seemed about the same as Andy, eight minutes across town, who ran a pub and was a chess savant, who showed you newspapers and explained where the grandmasters were making mistakes. And Andy seemed about the same as Jake, whose hobby was that his parents let him drink as much Sunny Delight as he wanted. When you’re a kid it’s all just flora and fauna. You learn prejudices slow, like which plants are poison.

***

I met Dr. Mike Mew at the house next door to Jake’s. This house had been a house, but now it was a dentist. It was called the Smile Centre. Outside was a laminate board that said so, accompanied by a fading photo of a perfect and disembodied grin.

Mike Mew is the head of the closest thing dentistry has to a cult. This was not true when I was nine but it is now. Mike and his father, John, believe that in humanity there is currently an epidemic of ugliness. They promise that you can build yourself a new and strong and masculine jawline, basically just by swallowing different. They call this mewing. His New York Times profile calls him a “celebrity to [the] incels,” but girls like him too. He has obtained adoration on both 4chan and TikTok. Mewing is a big thing, a real phenomenon.

Mike Mew also has, at time of writing, an ongoing misconduct hearing for, among other things, making a six-year-old boy wear head, neck, and inside-mouth appliances that allegedly led to the child being in so much pain he had “seizure-like episodes.” I was Mike Mew’s patient from ages nine to fifteen, or thereabouts. This all started in 2005.

Over Christmas last year, I showed my new fiancée around where I grew up. All the sights: Bellybutton Man’s spot and Jake’s house too. We then passed the Smile Centre, which has changed its name now.

“Oh my God,” she said, “you saw Mike Mew? Are you serious?”

This was how I learned that he was famous, that he had a Netflix documentary, and that my fiancée had seen him on TikTok and had been secretly mewing the whole time.

***

The waiting room of the Smile Centre subscribed to the most boring magazines in the world. Titles I remember being like “Interior Design for the Middle-Aged Wives of Small Business Owners” and “Regional Tatler.” There were leather sofas which were somehow always hot. There was a fish tank I once saw blue food coloring being added to.

Behind the desk was the person responsible: a sixtysomething white South African woman whose hair oscillated wildly between visits from gray to jet black and back again. She would say “Gibri-il Smitt” meanly, unsmilingly, and then I would go into the examination room, where her son was waiting for me.

The son was called Jeff, pronounced “Jiff.” It was a family business and Jeff was the main onsite dentist. I think I was there for a routine NHS visit when Jeff noticed my teeth were misaligned.

“His teeth are very misaligned,” I remember him telling my mother, who came into the examination room with me. I remember her saying: “Oh, dear.”

There was a second dentist present. This was Mike Mew.

Mike Mew’s practice was in London. Not the suburbs. He was the glamorous dentist. He had descended,

Jeff explained, a guru in the field of “orthotropics” (a word he made up), and I was very lucky that he was visiting.

At the next appointment, in a different room in the dentist house, Jeff filled my mouth with putty while Mike watched. At first, Mike mostly just watched. The bottom half first, then the top half. I had to bite down hard. I remember gagging on it, and the clay taste. It had to stay in my mouth for the longest time.

When Jeff took the top half out, one of my teeth came with it. This was very painful but I didn’t show it because I’m really brave.

Jeff pulled the tooth from the clay and inspected it, then handed it to Mike, who did the same.

“Don’t worry,” Mike said, to my mother, who was worrying. “It’s just a baby tooth. It would have come out in the next year or two anyway.”

“If you’re sure,” my mother said.

“We’ll have to redo the mold,” Mike said, smiling at the tooth, “once he stops bleeding.”

***

After this, Mike took over. Mike Mew made us look at some before-and-afters. He narrated these. He had a big laminated photo album and flipped through it.

“Look at this one. His face is long and thin, like Gabriel’s. His mouth was too small and his teeth were too crowded. Now look. His face is short and square and handsome. Look at the jawline. More handsome, right?”

“Uh,” I said, not wanting to say some gay shit.

“More handsome, right, Mum?” said Jeff.

“More square, definitely,” said my mother.

“That’s right!” said Mike, and he put the book down and smiled with lips closed, because he thought he’d convinced us.

***

Later, in the bathroom, I inspected my teeth in the mirror, and wondered why I was meant to care about which way they pointed.

Then I looked at some family photo albums, at photos I was in. Then I looked at myself in the mirror again to compare my current head with my previous head.

I wondered if the two dentists were right—whether my body was becoming ugly. And if it was, why it would do that to me.

This was something I had not thought about before.

***

Alongside the cast of my ugly teeth, and promises that I’d look that way forever unless action was taken, a bill was presented to my mother. I remember the number two thousand. I remember that we were broke. We couldn’t afford a car sometimes. Researching this, I asked my mother recently how we’d paid for it.

“We didn’t,” she said. “Your grandmother did.”

The clay version of me was used to shape the first appliances. They were made from translucent blue plastic and metal wire. One sat in the roof of my mouth and the other sat underneath my tongue. The metal wire was wrapped around my teeth on either side so that each appliance would stay in place.

Neither of them fit right at first. I lay on the hydraulic chair with my mouth open. Mike placed his hand in my hair and tried to force the upper appliance around my teeth.

When it didn’t go in, he handed it to Jeff, who went at it with pliers. Then Mike tried again.

They kept doing this until it did.

Both appliances had a miniature cog inside, right in the middle. Mike gave me a tiny key and some instructions.

“Give the key a quarter turn every night, before bed. The appliance will get wider, very slowly, with each turn. It will force your teeth apart. It will make your mouth wider. Got it?”

I nodded but didn’t say anything because my mouth was full of plastic and tiny cuts from being poked by the wires. It hurt to move. In my head, I called it the Crank.

My main memory of this period of my life is being unable to eat because my teeth and jaw hurt so much. And the appliance was so disgusting—it felt so embarrassing to remove before a meal—that I made up increasingly bizarre excuses to avoid eating in public. I did not want to look like a nerd.

In 2005 they hadn’t really invented anorexia for boys. So no one minded.

***

I gave up turning the Crank pretty quick. By this point Mike Mew had taken a special interest in me, or acted as though he had. He would say how perfect it was that I was starting puberty. Because my face was still growing—not fixed, like an adult’s—he could mold it to his desired proportions. And so he was coming to town for all of my sessions.

Mike became increasingly confused at the lack of progress. It didn’t seem to occur to him that I might be cheating, that I was a preteen boy, and might, on some fundamental level, not care enough about which direction my teeth went in.

He and Jeff tried removing some of my back teeth to make more room inside me. He operated. I was delighted to be fucking up their system, to be making them do exciting, unnecessary, time-consuming procedures.

It felt like revenge for the Crank.

I had just learned about communism from a cassette of a Clash album. I’m Che Guevara, I thought. I am the Che Guevara of Dental Appliances.

When the teeth were removed from my head I spat so much blood. My mother made a gasping sound.

“Don’t worry,” Mike said, “the blood mixes with the saliva. It looks more dramatic than it is.”

He turned on the miniature dentist tap and the blood began to wash slowly down the tiny sink.

The spiraling water turned from red to pink, then to nothing. I remember watching it, equal parts benzocaine-curious and horrified.

***

The operation, of course, did not work either. They changed tack, Mike and Jeff. They decided my chin was too far back in my head.

So they gave up on the Crank and recast my teeth and made a single appliance. This new appliance sat at the top of my mouth, its wires wrapping around my remaining back teeth. It had two long teeth of its own, the appliance, almost like fangs, which came down from the roof of my mouth, around my tongue, then curved, so that the pointed end of each was aimed at the inside of my gums.

Mike Mew explained this above my head. He would never raise the chair to speak to me.

“He’s a mouth breather. So he holds his jaw like this.”

He opened his mouth and retracted his chin and made a duhhhhhh sound.

I wanted to explain to Mike Mew that it was hay fever season. But his finger was in my mouth.

“So when he opens his mouth too wide, or doesn’t hold his jaw correctly, the appliance will give him a little prick on his gums.”

***

“Little prick” is an understatement: Mike Mew is a small and bizarre-looking man. He has a perfectly square head which, when Mike was a child, his dentist father molded using prototypical orthotropic methods. He is very short, and very slim, which gives the impression of his skull being about the same width as his waist. He wore, during our sessions, a tight shirt tucked into tight trousers, paired with square-framed glasses. He is bald, but fashionably so, and his manicured remaining hair frames the top of his strange little head very neatly. The impression he leaves is of an almost total cubeness, like a minor antagonist in a PlayStation game. He undoubtedly believes that his own physical format is somehow inherently correct, and in what he is selling: he has made himself into an example of it. “Look at your lips,” he said in one session. “Too big, too droopy, ugly. Now look at mine.” He turned to my mother. “This is how lips are meant to look. Firm and tight. Attractive.”

***

A few years passed. The fangs did work. I watched my face change. My chin went forward by the millimeter. I forced my teeth to stay together as long as I could, even while talking. I held my lips open to breathe when I had to. And each time I went to see Mike Mew and Jeff, they got out a tub of some kind of air-drying molten plastic and made the spikes on the fangs slightly longer, to force my chin farther and farther forward.

At the same time I had become six foot and skinny. I cycled everywhere and was tan all the time from the sun. I could buy cigarettes and lie on the grass and smoke them with my friends and people would sort of slide up and speak, then retreat. And once I worked out what was happening—which took a very long time, because I had never previously been cool, let alone attractive—all I could feel was a great unearnedness, a fraudulence of self, a deeply troubling sense that I was an accomplice in some great dental scam, and that anyone who was nice to me was being fundamentally misled, and that the only recourse I had was to make my personality as abrasive and unpleasant as I knew my body secretly was.

But also, when I stopped thinking about all that—when I could just let good things happen to me—life ruled. It ruled so much lol.

***

Mike Mew was delighted with my new fourteen-year-old face, and I thought that would be the end of it. But he didn’t stop there. Having fixed my jawline, he became concerned about my cheeks.

“His face is still very round,” he said. He put his gloved hand across my mouth and squeezed my cheeks so hard it hurt. “It feels like there’s too much muscle there.”

“He’s a bit mixed-race,” my mother said. She still came to the appointments, mostly. “He is kind of meant to look like that.”

Mike Mew looked at Jeff and said, “We need to give him cheekbones.”

***

The next part I can’t remember so well, partly because what Mike Mew says about mewing now is different from what I remember and partly because I had just discovered smoking weed and most long-term memories I’ve committed since are dreamlike and intangible, and trying to lift them from my brain feels, in a very pleasurable way, like lifting sand from a shimmering ocean I’m standing in.

Aside from their chemical effects, the suburban obtainment of drugs provided perhaps the first hint that my world was not what it seemed, of how it might be recast, of the impending strangeness of adulthood.

When buying drugs, you are asked to wait at street corners whose names you never knew. You see, for the first time, the insides of houses that do not belong to people with children. You learn fresh words, like ten-bag or cro, and find that language is the admission fee to new parts of your universe. You learn that all things have many secret sides to them, which were there all along.

***

Amid all this I remember Mike Mew and Jeff becoming very confused—again—even more so than before, about why there was too much muscle in my face. They theorized I was slacking in my sleep. They tried taping my mouth shut at night. Nothing worked.

There is a certain kind of depression that strikes people who reach the limits of a sales pitch they’ve treated as gospel. Mike Mew became distracted, grayer, more desolate. Less hyperactive and talkative. He trudged in his shoes that I remember as orthopedic. I remember feeling really bad for him.

But eventually, after some months, Mike Mew came into a session elated. He was engaged and curious. He had what seemed to be a new idea. When he was like this, he was charming, in his way. Boyish.

He gave me a tiny plastic dentist cup with water in it. He asked me to swallow while he watched.

He made me repeat this so many times. With my mouth open and his face very close to it. With my mouth closed. Until I could barely swallow any more.

“The problem is,” he said, “that you’re swallowing wrong. You’re swallowing with your tongue in the bottom of your mouth. It’s working the muscles in your cheeks. It’s making them too strong. Your tongue should be at the top, firmly. Watch me.”

Then he made me stand up and go to a mirror with him. And we took turns swallowing until he decided I was swallowing the way he wanted me to. This is the thing—the seed of the technique—that became known as mewing.

The Mews’ literature tells it differently. They say that Mike’s father invented the technique in the seventies. My guess is it’s somewhere in-between: based on the amount of time I spent lying open-mouthed in the hydraulic chair while Mike and Jeff hypothesized and pontificated about my teeth, Mike Mew was doing what is known in medical terms as throwing shit at a wall to see what stuck, and “swallowing different” was, when he was treating me, a semi-forgotten trick that he dusted off. That mewing was simple and cheap enough to preach online, thus catapulting Mew to viral dental superstardom, strikes me as a happy half-accident. Or, less than happy, depending on your view of Mike Mew.

***

Mike Mew cast my mouth in clay once more and made a new appliance that would allegedly force me to mew—to swallow correctly—the whole time. This time its fangs pointed at the insides of my cheeks.

I did not bother wearing it. I did my assigned at-home in-front-of-mirror swallowing practice maybe once if ever. I was fifteen and I did not want to become more of a cube. I was so bored of thinking about my own face. I had visions of being about to kiss girls and pausing to remove the blue plastic from my mouth, strands of my saliva following it like cheese on an advertisement pizza. This would not do.

So I told my mother that I’d had enough. And I never saw Mike Mew again.

***

I’ve not seen a dentist since. I tell myself that I’m English, that my teeth are meant to be terrible. For example, I did not go when, during a particularly dark heroin winter, my mouth began to fill with blood from an unknown source every couple of days. And I will not go for the tumor-shaped thing currently growing on my lower gums, either.

Once, in a particularly philosophical moment, Mike Mew told me: “Everything is discipline. You can apply what I’m teaching you now to anything you choose.”

I do not hate Mike Mew, because how could I? He was right. I love to grind away at my mouth, which was his work. To yellow it, to watch it chip. To make my body fat and flabby and then to bring it back to the bone. This, the learned and painful discipline of writing or sculpting a differently mangled self—of becoming compelling in spite of, or even because of, an ugliness—this is what I am grateful for. And the nicer jawline, too. Obviously.

***

Showing my beautiful new high-cheekboned, correctly swallowing fiancée around my hometown after she told me about Mew’s fame, I learned other things too. All the parts of the past that fresh eyes and hindsight had cast strange.

I learned that Andy the Savant’s pub had closed down during COVID. And that Bellybutton Man, who was actually harmless, had died some time ago.

And that the African church of the Holy Jemimas’ had been some kind of cult compound, and that TB Joshua had been faking exorcism seizures and miracles on video to obtain donations from gullible Europeans, and then raping a good deal of them, until the compound burned down in a potentially godsent fire. And that Fitzcarraldo had put out an acclaimed book by a reformed cultist, which the BBC was turning into a documentary.

And that perhaps my own face had once been strange enough to launch two billion TikTok views, from all the incels and looksmaxxing boys and girls who wanted to stop looking exactly like I had. And I was going to have to process that, somehow.

But what I’m actually saying is: it’s not that deep. It’s all about perspective. How much you see depends on what face you’re looking out of. And how much time you’ve had to look into it.

Gabriel Smith is the author of the novel Brat.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/WXCwzdx

Comments

Post a Comment