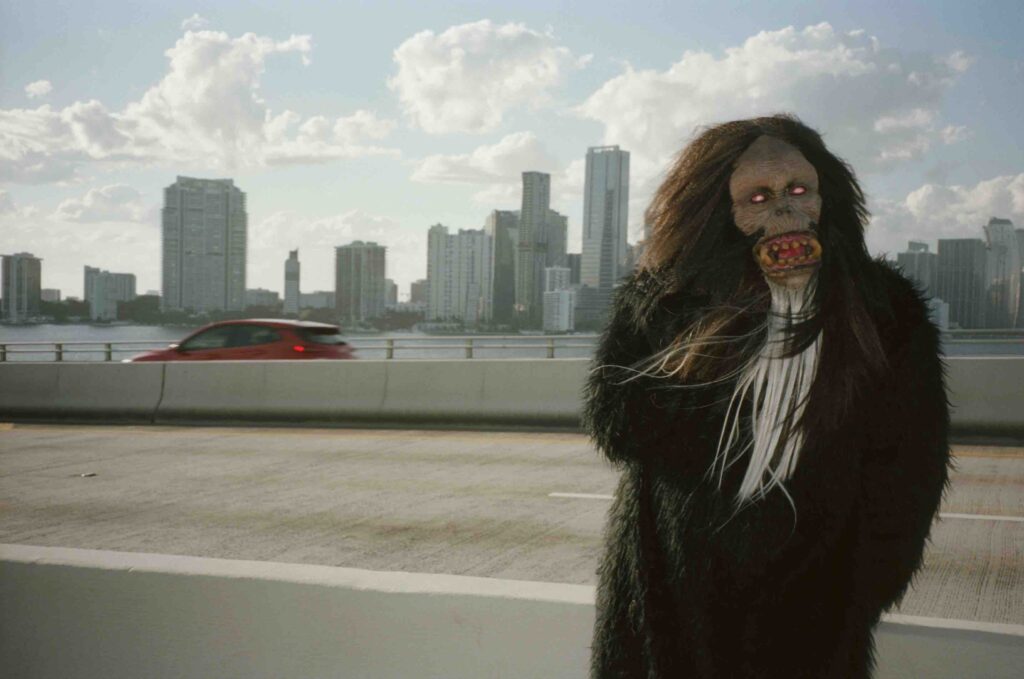

Skunk ape in costume against Miami skyline. Photograph by Josh Aronson.

The evening before the fourth annual Great Florida Bigfoot Conference in the north-central horse town of Ocala, I was in a buffet line at the VIP dinner, listening to a man describe his first encounter. “I was on an airboat near Turner River Road in the Glades and I saw it there,” he said. “At first, I confused it with a gator because it was hunched over, but then it stood up. It was probably eight feet tall. I could smell it too. I froze. It was like something had taken control over my body.” His story contained a common trope of Bigfoot encounters: awe and fear in the face of a higher power.

I sat down at a conference room round table and gnawed on an undercooked chicken quarter, looking around at my fellow VIPs, or as the conference’s master of ceremonies, Ryan “RPG” Golembeske, called us, the Bigfoot Mafia. Most of the other attendees were of retirement age. Their hats, tattoos, and car bumpers in the parking lot indicated that many were former military, police, and/or proud gun owners. Many were Trump supporters—beseeching fellow motorists to, as one bumper sticker read, MAKE THE FOREST GREAT AGAIN, a catchphrase which had been written out over an image of a Bigfoot on a turquoise background in the pines, rocking a pompadour. The sticker was a small oval on the larger spare wheel cover of a mid-aughts Chinook Concourse RV. Above it and below it, in Inspirational Quote Font, was the phrase “Once upon a time … is Now!” The couple who owned the RV cemented their identities with a big homemade TRUCKERS FOR TRUMP window decal next to a large handicap sticker. As a thirty-six-year-old progressive, I was an outlier in this crowd. But, like many, I was a believer.

It bears repeating: I believe in the existence of the Bigfoot, Sasquatch, Yeti, Wild Man, or, as it is called in South Florida, the Skunk Ape. There have been too many credible accounts and oral histories passed down over thousands of years to discount its/their existence. During my time working as a teacher on the Miccosukee Indian Reservation, I heard from students and elders very detailed and grave encounters with a large humanlike primate in the swamp. In the course of publishing Islandia Journal, a periodical of hidden local folklore and history, I also meet swamp enthusiasts—historians, hunters, hydrologists, et cetera—who describe encounters clearly. Though I’ve never had an encounter myself, I believe these stories intuitively, told by those who have nothing to gain from their telling. Unfortunately, no biological evidence supports the idea that Bigfoot exists. Attendees of the conference wax rhapsodically about what the future holds thanks to eDNA. The discovery of primate DNA in the water or dirt near an encounter location would rekindle the possibility of a biological Bigfoot, but for now, we’re waiting.

This absence of harder proof meant that the conference was, predictably, rife with speculation. At the VIP dinner, I sat next to Monica, one of my few fellow thirtysomethings in attendance. She was sunburnt and wore small round gold-rimmed glasses. She’d moved to Jacksonville from West Virginia with her partner, Joey, who told me later that she was just there to support Monica’s varying interests. While looking down and shuffling BBQ beans and mac and cheese around her styrofoam plate, Monica asked if I’d heard about the latest paranormal goings-on at Skinwalker Ranch in the Utah desert. Talking about large objects under mesas and anomalies in the sky, she gestured wildly. This struck me as off-base: we were at a Bigfoot conference, not storming Area 51. “It’s all connected,” she said, before explaining that Bigfoot tracks disappearing into dry creek beds weren’t the product of hoaxes but rather because Bigfoot travels using interdimensional portals. I expressed some doubt. “You can either close your mind,” she told me, “or open it to the very real possibility of infinite dimensions.”

After the VIP dinner, I drove down Ocala’s State Road 200—an asphalt expanse of strip malls—to Gator’s Dockside Restaurant. The person behind the popular Instagram account called @florida_bigfoot_hq was hosting a pre-conference get-together. The account is run by Brooke Moreland, a self-described “researcher of the strange and unusual,” who posts a combination of bikini, tattoo, fitness, and gun content on her personal Instagram. I saw her the next day at the conference wearing a BIGFOOT SPECIAL FORCES tank top. Against a setting sun, the tank’s Bigfoot walked holding an assault rifle. “He always sees you,” the shirt read, “But you will never see him.”

At the happy hour, I sat down next to Thomas and Todd, who’d driven down from Mississippi. In his free time, Todd designs Bigfoot-themed coasters. He doesn’t have an Etsy shop and wasn’t a vendor for the conference. “I just make ‘em for myself and for friends,” he told me. “Take one.” He handed me a coaster which read “Florida Skunk Ape: The Original Florida Man.” The coaster, disintegrating beneath the ring where his beer had been, was red, green, yellow, and black—the same colors you might find on a head shop ashtray. Thomas told me he was an HVAC repairman and heavy metal guitarist with a long ponytail who filled his time driving between jobs listening to Bigfoot podcasts. His dad got him into it. “It’s intergenerational for me,” he said.

The etymology of the name “Bigfoot” can be traced to Bluff Creek in California. In 1958, a bulldozer operator working for a logging outfit spotted sixteen-inch footprints next to his vehicle. His crew also reported encounters with a harmless area creature. Bigfoot hysteria entered the American psyche more broadly in the seventies after the release of the famous 1967 Patterson-Gimlin film, which purported to capture Bigfoot walking across Bluff Creek, California, in 16mm glory. Roger Patterson rented out movie theaters and screened the documentary which included the footage, and eventually sold rights to the BBC for use in one of their own TV docudramas. All of a sudden, people were heading into the woods in search of the creature. In 2019, the FBI released a trove of documents related to inquiries by Peter Byrne, the director of Oregon’s Bigfoot Information Center from all the way back in 1976. He’d been requesting an investigation into area sightings and a specific hair sample. Fifty years later, he finally got a reply in the files: the hair was from a deer. Many Floridians saw the possible existence of Bigfoot as a disruption to regularly scheduled hunting and real estate development. They wanted nothing to do with their resident Skunk Ape and took to the woods in angry mobs, except instead of pitchforks and torches, they brought rifles. They found clues, including a series of seventeen-inch footprints, but they were breadcrumbs that led nowhere. In 1977, hoping to quell the hysteria behind these hunts, Florida state representative Paul Nuckolls sponsored a bill to protect Skunk Apes from being hunted. The proposed law made it a misdemeanor to “take, possess, harm, or molest the Skunk Ape.” Ultimately, it did not make it through the legislature.

According to the Bigfoot Field Research Organization, which maintains the most extensive database of reported Bigfoot encounters around the world, Washington state has the most listed encounters and California has the second. These are not surprises. The Paterson-Gimlin film assured Bigfoot’s association with the woods and mountains of the Pacific Northwest. Florida comes in at number three. This surprises many. Florida has long marketed itself as a destination for beachgoing and fishing—a place where you can take a break from the coast and go see an alligator by the side of a road. The pine woods of Ocala’s National Forest and the mammal-rich cypress hammocks of the southern part of the state don’t make it onto postcards as often.

I asked my new friends at the @florida_bigfoot_hq event about this: Why is Florida a hotbed of Bigfoot encounters? “Plain and simple,” Todd replied, “You’ve got year-round freshwater and food.” He was referring to Florida’s weather, its springs, and a constantly replenishing store of wild turkeys, hogs, and other huntable animals. It was a sober, reasonable answer, and probably the best one I got the whole weekend, assuming you believe that Bigfoot is a biological being that requires food.

Skunk ape in costume. Photograph by Josh Aronson.

The next morning I drove to Rainbow Springs to take a dip in the seventy-two-degree water and mull over my own question. While driving, I’d passed the Villages, a retirement community with the power to influence presidential elections. I drove past swaths of clear-cut forest. I drove past roadside attractions like the Don Garlits Museum of Drag Racing, the Zipline Adventure Park, and Gatorland. Florida’s retirement communities and roadside attractions invite transplants to escape the malaise of a perceived American decline; they also often function as hotbeds of eccentricity, conspiracy theories, and right-wing politics. In 2021, at the first annual Great Florida Bigfoot Conference I’d attended, peak pandemic, it was paranoia which held my nose captive. Mask mandates were flouted in the merch aisles. Vendors sold SQUATCH LIVES MATTER stickers. One media company called the Soul Trap played a loop of a video about the Mark of the Beast.

In his recently published book The Secret History of Bigfoot, John O’Connor asked the scientist and writer Robert Michael Pyle if he thought Bigfooting and Trumpism were related. “Yes,” Pyle replied. “There’s a lot in common. As with the January 6th people, Bigfooters are all white guys. And they love their gear and their big trucks and their big guns and all of their infrared things. It’s not exactly the same crowd as January 6th, but it’s some of the same people.”

But the tone was different at the 2024 Great Florida Bigfoot Conference, which took place on June 8. Only one vendor called What the Sas? even really went there. When I asked them how sales were going for their gray tee with an illustration of a Bigfoot holding a LET’S GO BRANDON poster and storming the Capitol, the salesman shrugged and said, “Not as good as last year.”

According to the host, Gather Up Events, there were more than two thousand people at Ocala’s World Equestrian Center for the 2024 conference. The event was held in a giant, white warehouse with fifty-foot ceilings. Lines were twenty-deep at concession stands along one side of the room, where giant pretzels shaped like big feet were sold. Jovial attendees dipped their toes in cups of mustard. The center part of the hall was split in half. On one side were all the vendors, including a company called Area 52 Media Group, which offered a full suite of video editing and posting services for Bigfooters on expedition. Other tables sold night scopes, custom hunting knives, lawn signs, and advertised their YouTube channels and podcasts. A fifty-foot-wide screen hung above the stage on the other side of the room where lectures and panel discussions took place. The sides of the room were split by a wall of step-and-repeat head-in-hole boards, a space where, for a few minutes, you could become Bigfoot.

Many of the attendees were in the crowd to see a keynote address by Ranae Holland, the self-proclaimed “Skeptical Scientist” of the Bigfooting world. Holland does not believe in a biological Bigfoot. She was a star of Animal Planet’s Finding Bigfoot, a show which ran for a hundred episodes between 2011 and 2018. The show was a low budget, high-ad-dollar documentary-style and personality-driven program. The names of her costars still echo as refrains through the communities, like a Mount Rushmore of a Bigfooters. Spend time at a conference and you’ll hear them: Bobo Fay, Cliff Barackman, Matt Moneymaker, Ranae Holland. The cast never found a Bigfoot, but they had real, mysterious encounters and gave airtime to thousands of witnesses and local Bigfooting organizations. The show helped establish an industry which is thriving today.

Despite some scoffs from the crowd, Holland used her time on the Florida stage to champion LGBTQ rights in the Bigfooting world, espouse the virtues of indigenous land stewardship, and also revile her trolls, the so-called “Ranaesayers” of a very online community. Holland does not believe in a biological Bigfoot but rather an exquisite corpse of a celestial Bigfoot aggregated from various indigenous oral histories throughout the Pacific Northwest. The word Sasquatch, after all, is thought to derive from the Salish word Sasq’ets, which translates to “hairy man.”

When it came time for the Q&A, I stood up and asked Holland my enduring question: “Why Florida?” At first, she equivocated, but eventually came to a philosophical answer of sorts. “Florida,” she said. “It seems people in Florida are more open to sharing their experiences than in other places, for some reason.”

The reason intersects in some ways with conspiracy, certainly, and the state government’s movement toward freedom-cloaked fascism. But to funnel all Florida Bigfooters into an Erlenmeyer flask of religious fanaticism and conspiracy theory doesn’t do the subject justice. Bigfooters abound on all sides of the political spectrum, and our ranks include Peter Matthiessen, a left-wing political activist, environmental champion, and founding editor of The Paris Review. Matthiessen’s nephew Jeff Wheelwright has written extensively about his uncle’s passion. During his time in Nepal, researching a book that would become The Snow Leopard, Matthiessen claimed to spot “a dark shape” jump behind a boulder near a creek in a canyon. Bigfoot!

On my way out of the conference, I ran into the master of ceremonies and asked him how he felt. “It’s just so nice,” he said, “for people to have an event like this where they can talk about their experiences without feeling judged.”

During her keynote address, Holland talked about one of the most positive impacts of all this Bigfooting: that more people are getting outside and into the woods. Beyond that, maybe, people are looking to experience an awestruck, body-freezing encounter out in whatever wilderness is accessible. When I first got my driver’s license, I’d use the freedom to light out of Miami and speed on the Tamiami Trail into the Everglades. My friends and I would park at trailheads and hike in the ever-unfolding swamp, wondering if we might see something different this time. On one such trip, we pulled onto a dirt road near the Big Cypress to shoot scenes for a short film about a mythical golden alligator of the Everglades. We stopped the car, rolled down the windows, and took in the sound of the wind in the trees. We both heard the crackle of branches and agreed there was a shadowy shape along the road’s tree line. We ran out after it but found nothing in its wake but more trees, and solitude.

Rather than a fear of their fellow man, it might be that Florida Bigfooters are instead fearful of a world where the possibility of a Bigfoot doesn’t exist, that we live in a world which has been so overdeveloped that the numinous is relegated to plays of light and shadows. O’Connor writes in his Secret History about the 2009 Texas Bigfoot Conference, where Peter Matthiessen was convinced to give a keynote address. Talking to a local reporter about his interest in the subject, he waxed about the human need for story and myth. He ended his remarks by saying, “You know, stranger things have happened than Bigfoot.”

Jason Katz is the founding editor of Islandia Journal, a Miami-based periodical of subtropical myth, folklore, ecology, and cryptozoology.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/8ByFEWr

Comments

Post a Comment