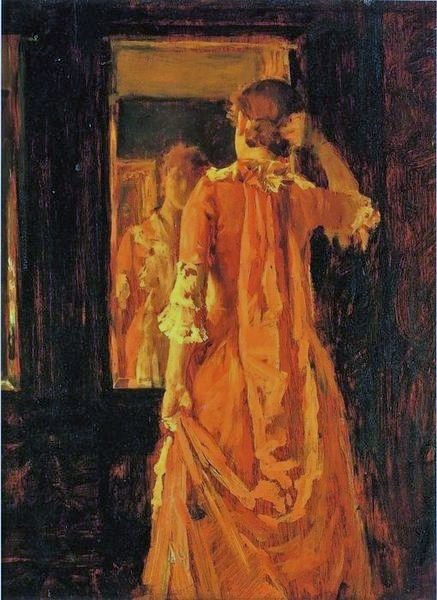

William Merritt Chase, Young Woman Before a Mirror. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

When I get dressed, I become a philosopher-king—not in the sense of presiding over utopia, but in the sense of trying to marry politics and intellect in the perfect imitation of God. Political considerations might include: destination, company, self-image, self-regard, in-group and out-group arrangements. The intellectual ones might involve: the weather, the way I am always too cold no matter the weather, the subway, the blisters on my feet, the laundry. When I get dressed, I have never once considered whether to add a belt. Belts have never struck me as a thing to “add”; pants either need a belt or they don’t. But some girls like to “add” one, and that’s fine too. I do consider the area where a belt might go—that stretch of midsection where the top of my pants meets the bottom of my shirt. It means a lot (to me), where exactly on my body that convergence takes place. If it’s lower, say a few inches below my belly button, I might get slouchier when I stand around, might remember being a kid in the early aughts, and I might in general feel more weighed down by the pull of gravity. If it’s higher up on my torso, I sit up straighter in my chair, I prefer a more substantial shoe, I feel more compact, more professional, more like my mother.

When I get dressed, I think about the last time I washed my hair and whether I’m going to wear my glasses or not. I am too much of a germophobe to wear shoes in the house, so I have no choice but to imagine the theoretical addition of a shoe, which I’ll put on last, when everything else is already a foregone conclusion. Lately, I can’t stop buying socks; it’s a compulsion. Wearing socks with no holes, that haven’t yet become limp from untold numbers of wash-and-dry cycles, has recently become crucial to my feeling of being able to face the world. On the other hand, I wear the same bra every single day, and it is such an essentially bland item of clothing that it feels like putting on my own skin. Nights are a different story: it’s important to invite spontaneity into your evening in whatever way you can.

When I get dressed I am confronted with the protean ecosystem of everything I have, everything I want, and why I have things that I’m not sure I want. Some things that I almost never buy, no matter their purported “quality,” are: dresses or skirts with slits, matching sets, sweaters with puffy shoulders, V-neck cardigans, Birkenstocks, tops where the pattern is only printed only on the front and not the back, jeans that are ripped at the knees, and anything described as a “tunic.” I’m not saying that you shouldn’t buy these things, I’m just telling you that I don’t want to. One thing I do want is to compose an ode to the tank top. The tank top is the shortest route to luxury—one of the only designer items affordable to those of us on a budget. A beautiful sweater or a handbag from wherever is out of the question, but you might, if it’s your birthday or you take an extra freelance gig, treat yourself to the flimsiest, paper-thinnest $200 tank top, knowing that the construction and the material is worth a fraction of that and feeling unreservedly that every dollar of difference is a delicious indecency. There’s nothing noble about being frivolous. But it can be wonderful to choose to be part of something bigger than you, which has a history and an artistry and—in the best case scenario—a point of view. It can even be worth an inordinate amount of your hard-won money. Anyways, when I get dressed, I reign over my little shelf of needlessly fancy tank tops and I feel alive.

There are some eternal quandaries. If I have to wear a sweater, a button-down shirt becomes untenable. (I don’t ever pop the collar neatly above my sweater, though I have nothing against prep, per se). If I have to wear tights, the prospect of choosing a skirt and a top and a sweater and socks and shoes becomes monstrous to me. If I choose to inflict tights upon myself, I will end up in a longer skirt so that I can avoid at least fifty percent of the lines that all those layers will generate on my body. I want to wear a pointed-toe kitten heel, but it feels impossible to do. If I have to wear a hat for warmth, I usually don’t.

When it’s time to take myself and my outfit into the world, I observe the doctrines of wilderness backpackers: I carry everything I could possibly need but no more than twenty percent of my body weight, as a general rule of thumb. This means I need a bag. When I see a woman without a bag or an extra layer somewhere on her person, I ask myself where on earth she could possibly be going. I think that she must live close by, and I wonder what her apartment looks like. When I see a man without a bag or an extra layer or anything else in his hands, his appearance of being untethered to a place or a purpose adds to his general unpredictability, and I cross the street.

I’ve noticed that most of my bags are green or blue. I’ve noticed that the most tempting thing to buy secondhand or vintage is a light jacket. They are often leather or suede or some other material that stands the test of time, and they’re less commitment than a coat, and they’re cheaper and more inoculated against trends. Most styles of light jackets from every recent era can be worn in the year 2024 without anyone batting an eye.

I’ve noticed that when I get dressed, I have to scrunch down my shoulders and shift my weight back on my feet so that my whole frame can fit in my mirror for the purpose of scrutiny. I don’t think I ever stand like this in my normal life, and I wonder if that makes any difference. It’s possible I only believe I like this dress because I only ever see it at this exact, awkwardly recessed angle. My nightmare is to appear like I’m wearing a costume of any kind. A friend once told me that blondes shouldn’t wear red, sending me into a monthslong deliberation. I think, now, that I can pull off an orange-y shade.

When I get dressed, I avoid at all costs thinking about how I might be doing something called “gender presentation.” As you can tell, this is all complicated enough as it is, and I am already running late.

I don’t have a closet in my little room. Instead, my clothes are all hanging, folded, or stuffed above and below me and on all sides. They are an immersive phenomenological experience, creeping out of every attempt at containment, constant, physical objects that I have to contend with as soon as I open my eyes in the morning. And in this way, it’s impossible for me to see my clothes as first and foremost a collection of textual emblems that others can read to decipher my social class, my taste, my upbringing, etc. If you interpret them in that way, once I am dressed, that’s your business. But the only time they feel full of symbolism and yet-unmade-meaning to me is when they’re shrouded in that floaty plastic, fresh from the dry cleaner. Otherwise, they are extremely literal. At the end of the day, they are in a heap on my floor and they have a mysterious stain on them, and there’s nothing metaphorical about that.

The reality is that there is a right answer when it comes to the question of what I should wear. I don’t mean that anyone else would notice if I got it wrong. But if I’ve just left the house and I’m waiting for the uptown train and I remember that I bought a long-sleeve dress two months ago that can only be worn with tall boots, and soon the season for long sleeves and tall boots will be over, and I have no plans in the foreseeable future to wear this dress, and the occasion for the dress was in fact tonight but it’s still dangling from a hanger in an overlooked corner of my bedroom, it will break my heart. Usually I can avoid this problem by making a dinner reservation, which offers another opportunity to get it right. However, if the long-sleeve dress is white (it is), and therefore wearing it to dinner means that I would fly too close to the sun, then I will wear it to a museum instead.

Isabel Cristo is a writer and researcher. She was born and raised in Brooklyn.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2vSJqyj

Comments

Post a Comment