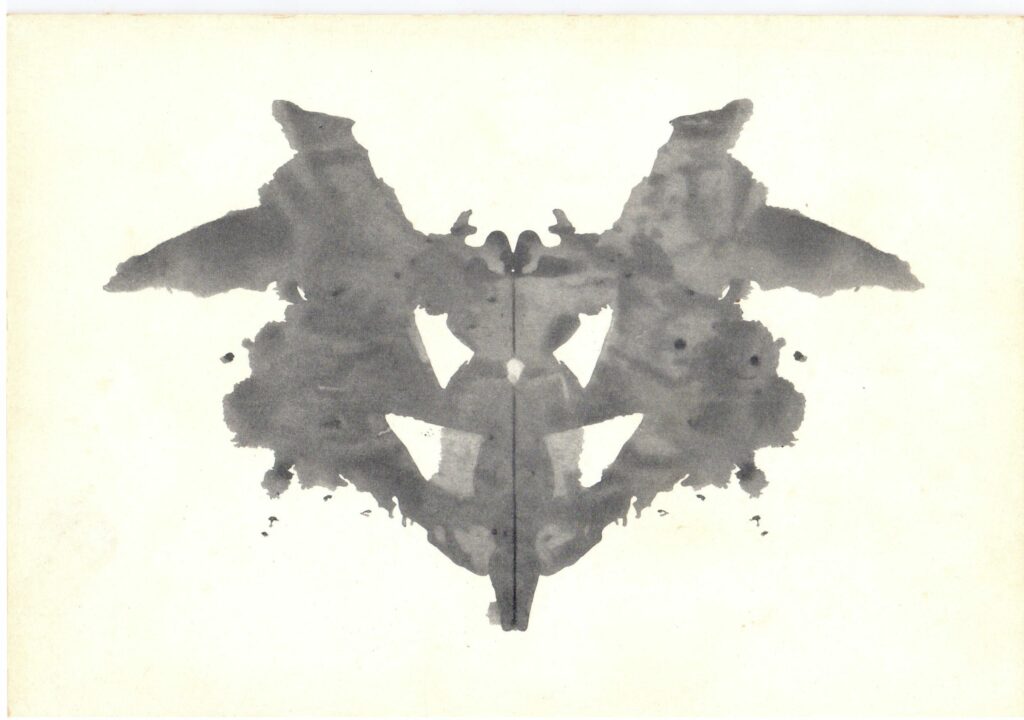

Rorschach plate that originally appeared in Psychodiagnostik by Hermann Rorschach (1921). Public domain.

Two monkeys with wings defecate suspending a ballerina whose skull is split. Her tutu reveals thighs from the fifties, toned. Their hands are on her poor wounded head; she has no feet. One of the monkeys, the one on the left, has a badly defined jawline. The woman has a perforated abdomen.

Two cartoon Polish men high-five. Their legs and their heads are red, to accentuate the fact that their heads are like socks. Their eyes are like their mouths, almost smiling at their mischief. They betray a body pact.

Two bald women with upturned noses, alien eyes, and prominent oval breasts. The separation between torso and hip through a knee and high heels propping up either two gardeners watering or two amphibians. On either side, fetuses in placenta or ghosts with their fingers to their lips, and with ribbons, evidently red, around their necks.

Rorschach plate that originally appeared in Psychodiagnostik by Hermann Rorschach (1921). Public domain.

Nothing. Or a monster with a half-hidden face, one eye visible, and something that splits its head. (Maybe a vagina.) You can see whiskers and cockroach pincers, Turkish shoes with stiletto heels and something unrecognizable between its legs. Or it’s a blurry monster that pulls them apart, and underneath, another monster or two that supports the first.

A butterfly walks with its feet warped, like it’s melting, dragging its wings. It has huge antennae and its back is to me; it sways to the right. Its expression is either looking off into the distance or perfect disappointment.

An extraterrestrial insect, thin, with four arms and two other small ones, its lower half unrecognizable. This part could also be two submarines with whiskered fish faces. It has a translucent shawl around its shoulders and its expression is of perversity or rage or desire or desire to kill.

Three open legs and a clitoris with a padlock. Could also be the profiles of two limp women with hands behind their backs.

Two possums climb a hill. At the base of it: two unhappy pigs and a playful devil or a very slim alien in an elegant shirt and suit jacket. A green bat with something else’s face, long, and above that a huge frog or anteater that consumes them all, with the help of the possums. This could also mean the frog ascends to heaven.

A swarm of hired pigs. Two Afrofuturistic hit women with tall hair wraps and two futuristic Ku Klux Klan members crossing swords.

From top to bottom: two emaciated men in hats dance, ludic, trophonic. Two insects fan them while riding on two other insects. Two marsupial mermaids drink a slurpee, intertwined, or play bagpipes while giving birth to fetuses in light or fish in amber. There’s a yellow-ocher ornamental set or something that doesn’t fully materialize; it has a torn root. Between them, something connects the mermaids’ nervous systems.

Rorschach plate that originally appeared in Psychodiagnostik by Hermann Rorschach (1921). Public domain.

Diana Garza Islas is a Mexican poet. Her Black Box Named Like to Me, in which this poem will appear, will be published by Ugly Duckling Presse in fall 2024. This poem was translated by Cal Paule. Paule is a translator, poet, and gender studies teacher.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/qcbB0hz

Comments

Post a Comment