If you attended school in the U.S. like I did, the first poem you wrote as a child was, more likely than not, some version of the Japanese haiku. As a grown-up, you may have gone on to read the haiku masters Matsuo Basho, Kobayashi Issa, and Yosa Buson—the Paul McCartney, John Lennon, and George Harrison of Edo-period Japan. But most Western readers have yet to twig on to Masaoka Shiki, the Ringo Starr of the haiku pantheon. Born more than two hundred years after Basho, this latecomer to the declining literary form launched a haiku revival in late-nineteenth-century Japan, writing haiku about modern subjects like baseball (“dandelions / the baseball rolled / through them”) and penning a memorable little essay titled “Haiku on Shit.” By the time of his death from tuberculosis at thirty-four, Shiki had written nearly twenty thousand verses and founded a new school of haiku poetry with its own literary magazine, Hototogisu, which continues to publish haiku today.

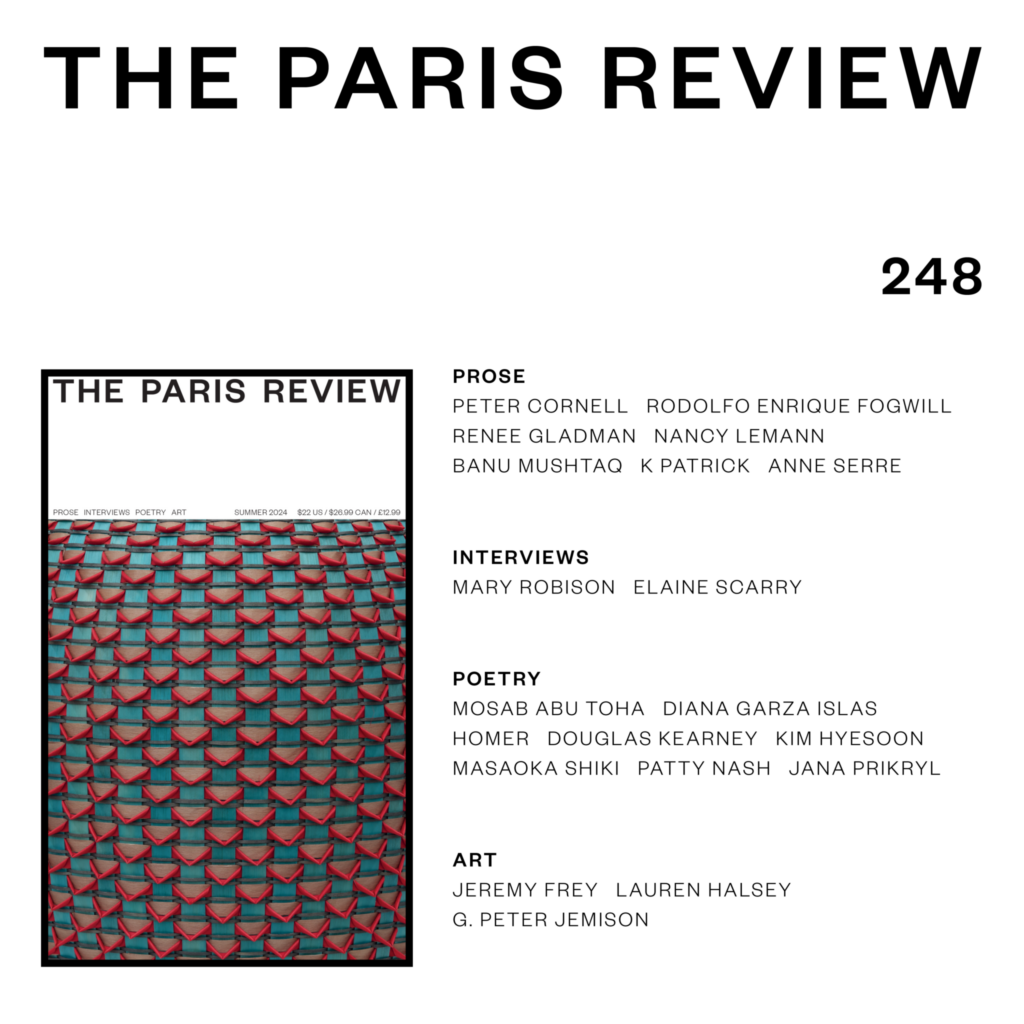

In the new Summer issue of The Paris Review, we present a series of ten never-before-published literary sketches by Shiki, composed from his sickbed, each one depicting a bowl of live carp. In one poem, Shiki zeroes in on “carp tails / moving in the bowl”; in another, we catch sight of “carp shoulders / brimming in the bowl”; and in another, we watch “carp blowing / bubbles” by the poet’s bedside. Only at the end of this Muybridgean study of animal motion does Shiki’s subject come to rest:

carp asleep

in the shallow bowl

water in spring

Reading the poet’s variations on a theme feels like scrolling through drafts of a translation in progress—only it’s reality itself that Shiki is translating into haiku form. Should the poem’s last word go to the seasons, the elements, or existence itself? And what’s the difference, if any, between a “large low bowl” and a “shallow bowl”? As Shiki observes in Abby Ryder-Huth’s prismatic translation, the poems “aren’t really ten haiku, just trying to put one thought ten ways.” Like Wallace Stevens’s blackbird, Shiki’s still life rarely stays still.

Elsewhere in our Summer issue, Daniel Mendelsohn visits Kalypso’s island in a passage from his new translation of The Odyssey; you’ll find yourself walking backward “with a clock hung from your heart” through a nightmarish incantation by the shamanistic Korean poet Kim Hyesoon, translated by Cindy Juyoung Ok; the Mexican poet and visual artist Diana Garza Islas introduces us, in a translation by Cal Paule, to a strange little place called “Engaland”; and the Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha meditates on another kind of still life:

My books remain on the shelves as I left them last year

but all the words have died.

I search for my favorite book,

Out of Place.

I find it lying lonely in a drawer,

next to the photo album and my old Nokia phone.

The final line of Abu Toha’s poem leaves us with a parting glimpse of “the sea, the sea,” a haunting image that reverberates with the poet’s favorite book, Edward Said’s memoir Out of Place. It also makes me think of Iris Murdoch’s novel, whose title might have come from a line in a Paul Valéry poem—“La mer, la mer, toujours recommencée”—or from the retreating Greek soldiers’ exultant cries on sighting the sea that will take them home in Xenophon’s Anabasis: “Thálatta! Thálatta!” Every great poem is an echo chamber. In Jana Prikryl’s “The Channel” or the ending of Douglas Kearney’s “Apology tour.,” you’ll hear Shakespeare surging through contemporary verse. Like the sound of the ocean in a seashell, poetry needs you, its attentive listeners, in order to exist. As Patty Nash puts it in her poem “Metropolitan”:

- It all happens on the inside,

- And yet it’s worthless

- If you don’t perceive it.

Srikanth Reddy is The Paris Review‘s poetry editor.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3yMbpQ7

Comments

Post a Comment