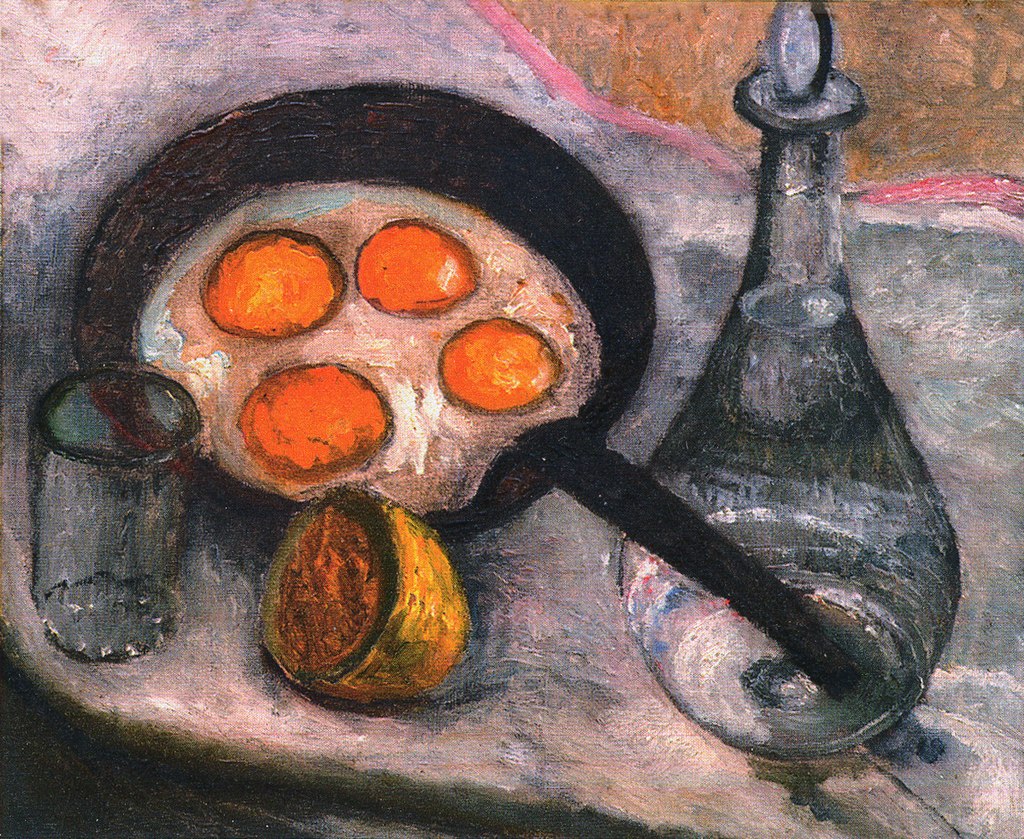

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Still Life with Fried Eggs in a Pan, c. 1905. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Rainer Maria Rilke and the Expressionist painter Paula Modersohn-Becker met in the summer of 1900 in the German artists’ colony of Worpswede, which lies to the north of Bremen in a flat, windswept landscape of peat bogs, heather, and silver birch trees. Born just a year apart in the mid-1870s, Modersohn-Becker and Rilke were trailblazers in art and poetry at the dawn of the twentieth century. Their correspondence bears witness to their lively, ongoing dialogue and underlying creative affinities. Modersohn-Becker’s haunting portrait of Rilke, and Rilke’s meditative poem “Requiem for a Friend,” written in the aftermath of Modersohn-Becker’s untimely death, commemorate the importance each held in the other’s life.

Below are three letters from Rilke to Modersohn-Becker, written late in the year 1900.

—Jill Lloyd

Schmargendorf, Misdroyer Strasse 1

25 October 1900

My apartment has just now been completed. I don’t know which object did it; suddenly everything quietened down and it immediately became inhabited and familiar, as if no longer new—and yet … I would very much like to tell you how everything is, and where and why things are the way they are. Well, there is a small, unremarkable entryway, and a kitchen that will become interesting due only to my daily attempts at cooking (I have to prepare everything myself!); from the entryway you step through a small door and under a dark red curtain of heavy, woven linen (sold at Bernheimer’s in Munich as toile japonaise) into my very large study. There is a huge three-part window partially wedged into a bay as wide as the room itself. To the right of the bay, a glass door leads to a small balcony, while on the left the bay is joined by a blank wall to the wall of the study. Underneath the window there is a broad bench covered with a blue-and-red blanket from Abruzzo(!), and two steps in front of this bench, in the center of the room, is the main desk. There is a second, quite long desk set up as a working table for evening tasks—independent of the window, at an angle in front of the stove, and diagonally blocking the corner. To the left of the large window there hangs a narrow rug with a colorful border that keeps that corner dark, and in front of it stands the yellow samovar on a Russian base, surrounded by some Russian things, images, and holy icons. A very broad chair covered by a good, antique Turkish rug connects (to the left of the wall) to the cupboard for the samovar so that it’s easy to put down one’s glass of tea there. The Turkish blanket is stretched up the wall to the so-called ‘Rubens’—the Adoration of the Magi (oil painting—old, 2 meters long, 47 centimeters high)—and provides the backdrop for the best heirloom: a family crest in a precious silver frame. Then there is a small green table where I have to eat what I cook—and a small sideboard. Since I had to make do with a lot of existing things, including the gentle and not at all obtrusive wallpaper (dull yellow with blurred, quietly swaying carnations in pale red), I created particular backgrounds on which the pictures are hung and to which they are all connected in some way or other: for example the Turkish blanket underneath the crest and, on the opposite wall (which is dominated by an eight-unit bookshelf with an attached narrow bench), a precious green-and-gold cloth on top of which I have placed pictures of ancestors and forefathers… But what is the point of telling you all this? I realize that it will not amount to much more than what can be gleaned from a school essay or from old-fashioned travel accounts, or at best I will reach the level of stage directions for a theater … but I did not want to give you those, Miss Becker, but rather (I realize it late enough!) something of the play that is performed in this room, among these things, with them, for them … action, action! For heaven’s sake no description! And the play? … perhaps it hasn’t started yet?

Oh, my dear friend,—now the stage is truly set and, since it has been built of more than cardboard, it will probably last for a while … there are chrysanthemums; at the moment I don’t know where they are, but it calms me to know that they are here. It is evening. Silence. It seems almost impossible that you will not simply appear in my room at this moment—since everything has been set up and the pictures are hung on walls that, seen from the out-side, have now become the walls of my little home. I am waiting: waiting for you and for Clara Westhoff and Vogeler and for Sunday and for the song … and nothing is going to come. I know that nothing is going to come, and yet I wait. I am almost afraid to wish for others to come—there are the Russians with whom I am supposed to be working, and very seldom anyone else. But one morning I will truly wish for it and start working. Today, however, on this first evening in the finished rooms, I may just permit myself to sit—to be filled with longing and nothing else. My thoughts roam among your houses. My heart is suspended somewhere in the wind and rings out. My hands rest open and empty, like half shells from which the pearl has been removed. But do not mistake this for unhappiness, but rather for a kind of celebration that is gently ushering in my winter. I am grateful when I think of all that.

Yours, Rainer Maria Rilke

Today I am sending you a copy of the Revue de Paris with the play Mirage by George [sic] Rodenbach;—do you remember? And my kind regards! Also for your sister Milly and your little sister.

***

Schmargendorf

October 28, 1900

You have a knack for making letters as beautiful as evening hours. I read your letter frequently, and you should read and treasure what I wrote in response when you receive it, in the evening.

Strophes

I am with you, you Sunday evening ones.

My life is radiantly glowing and bright.

I am conversing, but compared to other times

all words have fled my lips and mind,

so that my silence rises up and blooms.For these are songs: a beautiful silence of many,

that rises up from one person in rays.

The violin player is always alone,—

And, among the others, the slim player

is the most silent one, the one who does not speak.I am with you, you gentle and attentive ones.

You are the columns of my solitude.

I am with you: do not give me a name,

so that I can be with you even from afar …

Just as great, sprawling gardens

sometimes bear words of foreign woods

on their quiet, darkening paths …You are quite close to how I feel. I am

not mistaken. This hour now resembles

the hours with the white background.

Around me, the silence resounds with many sounds.

Music! Music! Orderer of sounds,

take what is scattered here at dusk,

lure pearls, rolled away, back onto strands …Each thing locks in a prisoner.

Go, music, to each thing and lead

out of every thing’s doorway

the longtime fearful figures.

In pairs that hold each other’s hands

they follow you and go along the measures

with which we count the hours deep,—

they go, regally, their heads in wreaths,

from our rooms which had forgotten us.I am with you, who listen to the sound,

that always hums and for which we sometimes exist;

we lost our fear that it will fade away.

Music is creation. Soul of song,

many things you turn into a structure,

by entering into those many things.

With you all women are one woman;

you link those—who are girls like silver rings

into cool chains that tie together spring.

To boys you give a sense that they could find a

spot toward which the world extends,

and old people already blinded by the day

live on only because they lean on you.

And men have longed for you.I am with you. Among brothers, among trees,

one is as calm as when amongst you all.

I glean from dreams this sense of feeling soothed:

this being-without-fear of missing something

and this pleasure taken in what one knows.

Simple existence, offered to the heavens,

like ponds that stay forever open,

telling more beautifully of the wind’s experience,

and holding days and evening breeze,

safe above the abyss that is eternal.I am with you. Am thankful to you both

who are like sisters of my soul;

for my soul wears a girl’s dress

and its hair is silken to the touch.

I rarely glimpse its cool hands;

for behind walls it lives quite far away,

as if in a tower not yet sprung free

by me, and hardly aware that I will arrive.But I pass through the winds of earth

toward the rising wall,

behind which, in uncomprehended grief,

resides my soul … You know it better;

you’ve seen it, more familiar than myself.

You are the sisters of my bride.

……………

Be good to it.

Be kind to it, the blond sister here.

Speak to it with the rising moon.

Tell her of yourselves. Tell her about me.

I am waiting for a very beautiful hour, and the most beautiful, most open, and most receptive that arrives I will carry to Maid. For you must measure my capacity to give against what I have received. I am an echo. And you were a great sound whose concluding syllables I repeat from afar. Give my regards to Clara Westhoff with this Sunday letter.

Yours, Rainer Maria Rilke

***

Schmargendorf

November 5, 1900

How gloriously my place is turning out for me. Imagine, dear Paula Becker: I had on my desk a copper pitcher with slowly wilting dahlias the color of old ivory, just so that all that was needed to add to them to create a miracle were these fantastic and wonderful cabbage leaves. The miracle occurred and worked its magic.—On the bench attached to the bookshelf there was a tall, narrow vase with a few branches of rose hip arranged with heavy clusters of red rowan berries, and the fir branches were ringed by great yellow and golden chestnut leaves that are like the spread-out hands of autumn wanting to grasp the sun’s rays. But now that the sun’s rays no longer plod along but have grown wings, no chestnut leaf is going to catch a ray. Everything around me (I mean to say by means of this list) was prepared to receive the autumn with which you surprised and delighted me. There was already a spot ready, arranged by destiny, for each piece of your abundant autumn. Including the chain of chestnuts. Only in my house it does not hang on the wall; I sometimes take it out and pass it through my fingers like a rosary (you know about these Catholic prayer beads?). For each bead of such rosaries, one has to recite a particular prayer: I emulate this devout rule by thinking with each chestnut of something lovely that refers to you and Clara Westhoff. Which led me to discover that there are not enough chestnuts.

The first days of November are always Catholic days for me. The second day of November is All Souls’ Day, which up to my sixteenth or seventeenth birthday I had always, no matter where I was living at the time, spent in churchyards—often visiting unknown graves as well as graves of relatives and ancestors, and gravesites that I could not make sense of and that I had to think about during the lengthening winter nights. That was probably when the thought first occurred to me that every hour that we live is the hour of death for someone, and that there may even be more hours of dying than hours of the living. Death has a clock’s face with countless numbers … Now it has been years since I stopped visiting graves on All Souls’ Day. Now I only make a trip to visit Heinrich von Kleist out in Wannsee at this time of year. He died out there in late November; during a season when many shots resound in the empty forest, two heavy shots from his gun also rang out. They barely differed from the other shots, though they were perhaps a bit more forceful, shorter, more breathless … But in the heavy air all sounds become similar and grow dull amidst the many soft leaves floating down everywhere.

But I realize that this is no letter for you, and actually not one for me either. I long for you, dear friend. Farewell.

Yours, Rainer Maria Rilke

Soon I’ll copy for you the song “You pale child, each evening … ,” and then I will send it to you. It does not even exist if it’s not in your possession—especially that one, which first came into being with you, so to speak. During one of these evening hours. Please send my regards to Clara Westhoff and your sisters Milly and Herma. And do not be upset about this letter. Different types of letter will come again!

The Modersohn-Becker/Rilke Correspondence, translated by Ulrich Baer and with an introduction by Jill Lloyd, is forthcoming from ERIS Press this month.

Ulrich Baer is the author of of What Snowflakes Get Right: Free Speech, Truth and Equality in the University; Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma; and The Dark Interval: Rilke’s Letters for the Grieving Heart. He teaches at New York University.

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) was an Austrian writer best known for his poetry collections The Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus, and a novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge.

Jill Lloyd is an art historian and curator. She has coedited numerous exhibition catalogues and is the author of German Expressionism, Primitivism and Modernity and The Undiscovered Expressionist: A Life of Marie-Louise Von Motesiczky.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/naEsM5h

Comments

Post a Comment