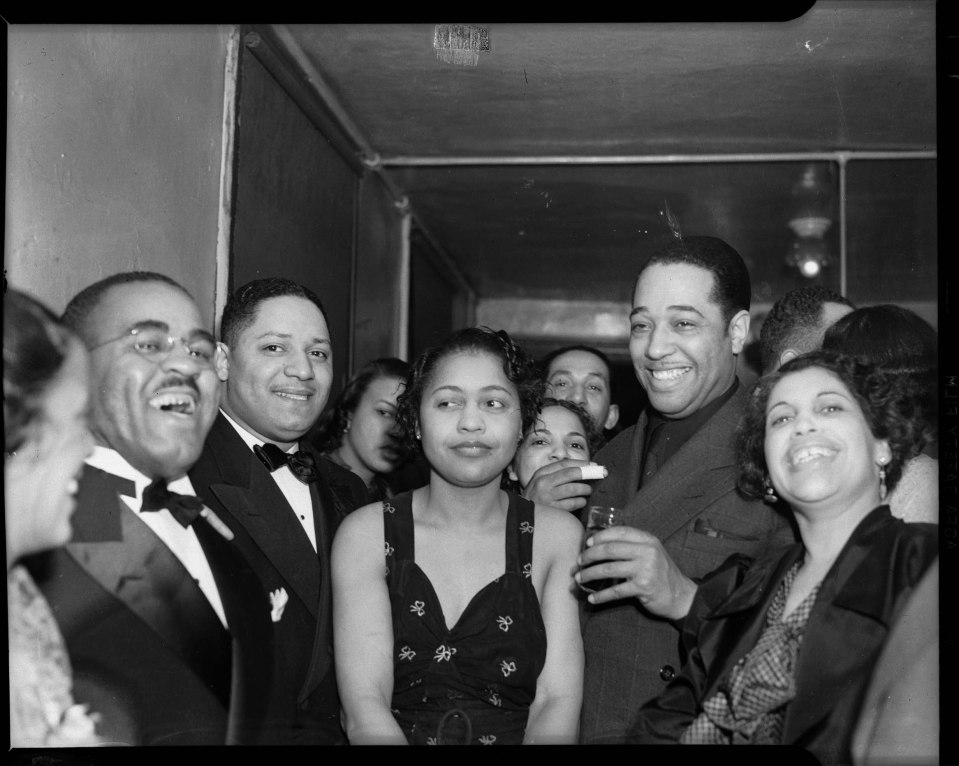

Duke Ellington with a group posed in Loendi Club for Synchonettes Club party, by Charles “Teenie” Harris, 1938. Copyright: © 2006 Carnegie Museum of Art.

Toward the northern reaches of the Appalachian Mountains, at the point where the East Coast ends and the great American Midwest begins, three rivers meet. The Allegheny flows from the north, gathering the tributaries of western New York State. The Monongahela cascades from the south, through the hills and hollers of West Virginia. Together, they form the headwaters of the Ohio, which meanders west all the way to Illinois, where it connects to the mighty Mississippi and its tentacles reach from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Because of its strategic value, the intersection of these three rivers had generals named Braddock and Forbes and Washington fighting to control the surrounding patch of Western Pennsylvania two decades before the War for Independence. Because it allowed steamboats to reach the coal deposits in the nearby hills, the watery nexus made the city that grew up around it the nation’s largest producer of steel and created the vast wealth of businessmen and financiers named Carnegie, Frick, Westinghouse, and Mellon whose legacies live on in the renowned libraries, foundations, and art collections funded by their fortunes.

That story of Pittsburgh is well documented. Far less chronicled, but just as extraordinary, is the confluence of forces that made the black population of the city, for a brief but glorious stretch of the twentieth century, one of the most vibrant and consequential communities of color in U.S. history. Like millions of other blacks, they came north before and during the Great Migration, many of them from the upper parts of the Old South, from states such as Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, and North Carolina. As likely as not to have been descendants of house slaves or “free men of color,” these migrants arrived with high degrees of literacy, musical fluency, and religious discipline (as well as a tendency toward light skin that betrayed their history of mixing with white masters, and with one another). Once they settled in Pittsburgh, they had educational opportunities that were rare for blacks of the era, thanks to abolitionist-sponsored university scholarships and integrated public high schools with lavish Gilded Age funding. Whether or not they succeeded in finding jobs in Pittsburgh’s steel mills (and often they did not), they inhaled a spirit of commerce that hung, quite literally, in the dark, sulfurous air.

The result was a black version of the story of fifteenth-century Florence and early-twentieth-century Vienna: a miraculous flowering of social and cultural achievement all at once, in one small city. In its heyday, from the 1920s until the late 1950s, Pittsburgh’s black population was less than a quarter the size of New York City’s, and a third the size of Chicago’s—those two much larger metropolises that have been associated with the phenomenon of a black Renaissance. Yet during those decades, it was Pittsburgh that produced the best-written, widest-selling and most influential black newspaper in America: The Pittsburgh Courier. From a four-page pamphlet of poetry and local oddities, its leader, Robert L. Vann, built the Courier into a publication with fourteen regional editions, a circulation of almost half a million at its zenith, and an avid following in black homes, barbershops, and beauty salons across the country.

In the 1930s, Vann used the Courier as a soapbox to urge black voters to abandon the Republican Party of Lincoln and embrace the Democratic Party of FDR, beginning a great political migration that transformed the electoral landscape and that reverberates to this day. In the 1940s, the Courier led crusades to rally blacks to support World War II, to win combat roles for Negro soldiers, and to demand greater equality at home in exchange for that patriotism and sacrifice. In the 1950s, its reporters—led by several intrepid female journalists—exposed the betrayal of the promise of a “Double Victory” and chronicled the first great battles of the civil rights movement.

In the world of sports, two Courier reporters, Chester Washington and Bill Nunn, helped make Joe Louis a hero to black America and a sympathetic heavyweight champion to white boxing fans. Two ruthless business-men, racketeer Gus Greenlee and Cum Posey, the son of a Gilded Age shipping tycoon, turned the city’s black baseball teams, the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Homestead Grays, into the most fearsome squads in the annals of the Negro Leagues, uniting such future Hall of Famers as Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, slugger Buck Leonard, and base-stealing demon “Cool Papa” Bell. Another Courier sportswriter, Wendell Smith, led a campaign to integrate the big leagues, and was the first person to call the attention of Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey to a young Negro League shortstop named Jackie Robinson. While covering Robinson’s first seasons in the white minor and major leagues, Smith served as Jackie’s roommate, chauffeur, counselor, and mouthpiece, helping to soothe the historic rookie’s private temper and fashion the public image of dignity that was as crucial to his success as power at the plate and speed around the bases.

In the realm of the arts, Pittsburgh produced three of the most electrifying and influential jazz pianists of the era: Earl “Fatha” Hines, Mary Lou Williams, and the dazzling Erroll Garner. It was in Pittsburgh that Billy Strayhorn grew up and met Duke Ellington, beginning a partnership that would yield the finest orchestral jazz of all time. Another Pittsburgh native, Billy Eckstine, became the most popular black singer of the 1940s and early 1950s, and played a less remembered but equally groundbreaking role in uniting Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sarah Vaughan on the swing era bandstands that helped give rise to bebop. Then, in the mid-1940s, in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, a black maid born in North Carolina who had taken up with a white German baker gave birth to a boy who grew up to become America’s greatest black playwright.

Today, black Pittsburgh is best known as the setting of August Wilson’s sweeping Century Cycle: Fences, The Piano Lesson, and seven more of the ten plays he wrote depicting black life in each decade of the twentieth century. Wilson conjured it as a world full of tormented, struggling strivers held back by white racism and their own personal demons. It was a portrait that reflected the playwright’s affection for the black working class, as well as the harsh reality of what became of the Hill District and the city’s other black enclaves after the 1950s, when they were hit by a perfect storm of industrial decline, disastrous urban renewal policies, and black middle-class brain drain. So powerful was Wilson’s imaginary universe, and so thorough the destruction of those neighborhoods, that few in the thousands of audiences that have seen his plays or flocked to the movies that are now being made from them would know that there was once more to the actual place that the Courier writers liked to call Smoketown.

But there was more. A great deal more. Under the dusky skies of Smoketown, there was a glittering saga.

Mark Whitaker is the author of the memoir My Long Trip Home. The former managing editor of CNN Worldwide, he was previously the Washington bureau chief for NBC News and a reporter at Newsweek, where he became the first African-American leader of a national newsweekly.

Copyright © 2018 by Mark Whitaker. From the forthcoming book SMOKETOWN: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance by Mark Whitaker to be published by Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

from The Paris Review http://ift.tt/2n0Pafy

Comments

Post a Comment