Zoe Leonard, TV Wheelbarrow, 2001, Dye transfer print, 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6 cm). Collection of the New York Public Library; Funds from the Estate of Leroy A. Moses, 2005

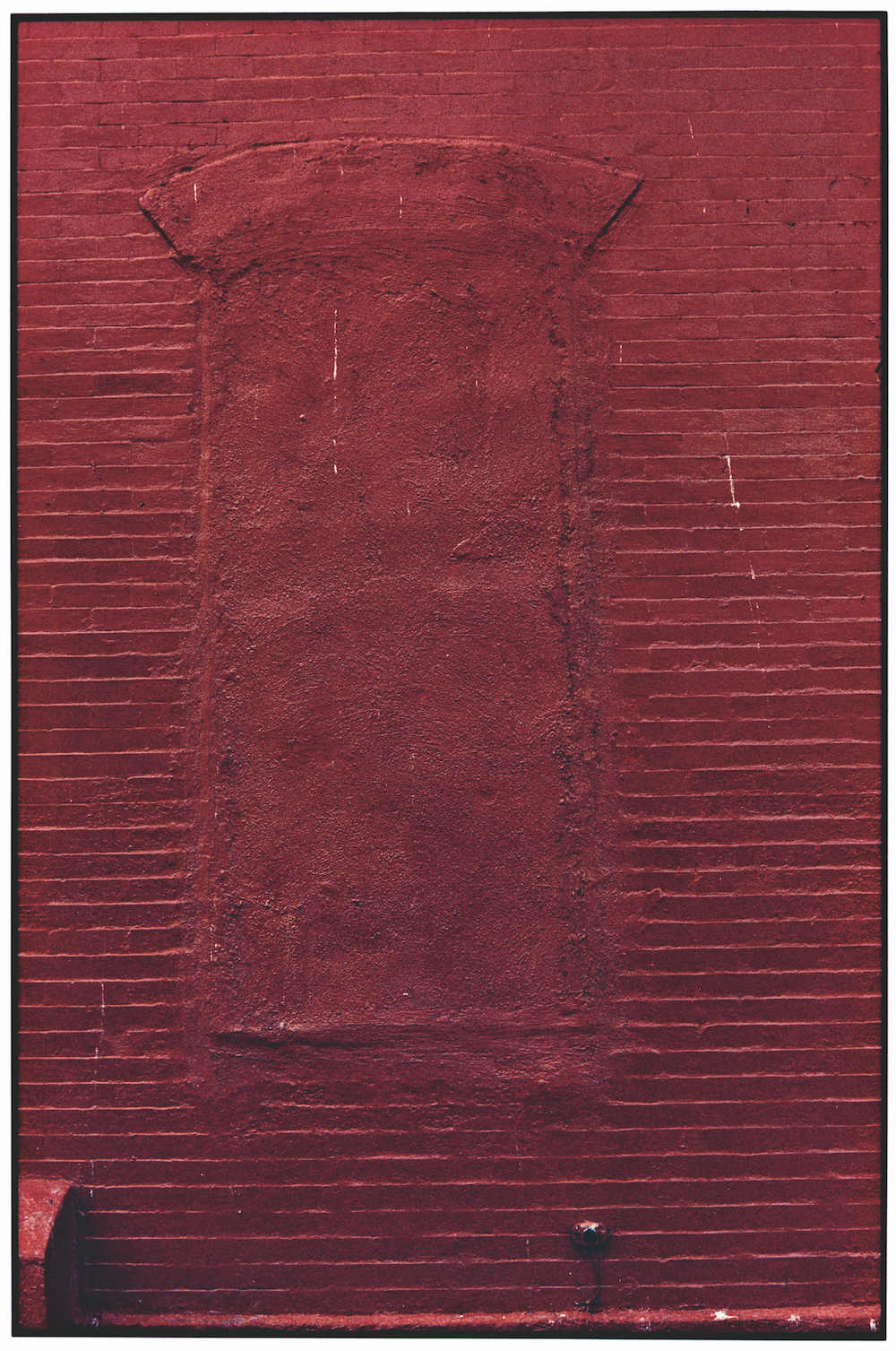

Never have I wanted to touch a photograph as badly as I wanted to touch Zoe Leonard’s Red Wall 2001/2003 (Leonard typically includes two dates with each photograph, the first signaling when the photo was taken, the second when it was printed). It’s an image of such saturated—such tactile—redness that it was, for a beat, difficult to accept that it was only a representation of a wall, flat and smooth and framed. Red Wall is a minimalist monochrome wet dream that inspires a maximalist yearning—an outsized, outrageous need.

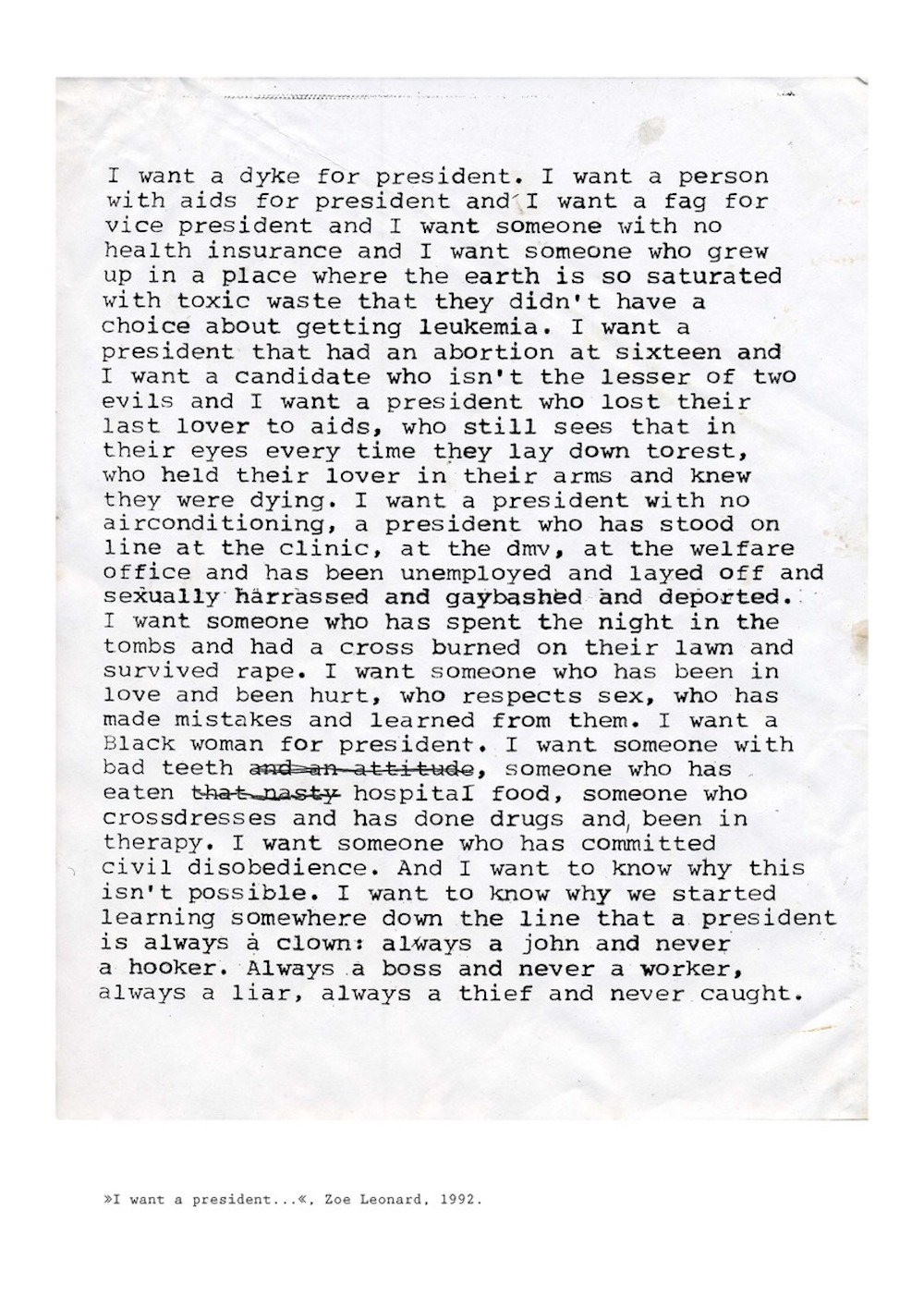

Leonard is a photographer and a sculptor. She is also an activist, and her work with the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) serves as a model for conscientious, personally risky political involvement. Her samizdat poem “I want a president,” originally written to celebrate Eileen Myles’s 1992 “openly female” (in the poet’s words) run for the presidency, was originally meant to run in a small journal that shut down right before publication. In 2006, it was printed as an insert postcard in the journal LTTR, and in 2016 it appeared on a billboard at the foot of the High Line. “I want a dyke for president. I want a person with aids for president,” the poem begins. It ends, “I want to know why we started learning somewhere down the line that a president is always a clown. Always a john and never a hooker. Always a boss and never a worker. Always a liar, always a thief, and never caught.”

As the scholar Ann Cvetkovich has written, Leonard is an archivist of feeling. What might otherwise remain inchoate—rage, mourning, loneliness, alienation—coalesces in her photographs and in her installations of collected ephemera. Leonard’s work is an invitation to interrogate how our depressions, despairs, and desires can be harnessed as political perspectives. Our emotional responses, according to Leonard, are a form of political positioning. The resulting pieces caress the eye and prod at the conscience. They are demanding, but also witty and companionable, and together they articulate how one might take action in a society that incentivizes passive complicity.

Zoe Leonard, Red Wall, 2001/2003. Dye transfer print, 29 11/16 × 20 7/16 in. (75.4 × 52 cm), Collection of the artist; courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York

Zoe Leonard: Survey, the title of her current mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, suggests the importance of looking from many angles. As the wall text at the exhibition’s entrance has it, “’to survey’ is…to look out a place or site and gauge it from multiple viewpoints in an effort to understand and describe it.” One of Leonard’s newest sculptures, How to Take Good Pictures (2018), is comprised of over one thousand copies of the eponymous Kodak manual, stacked in columns of varying heights. Evoking a cityscape or a bar graph, and set against the grand expanse of the Whitney’s westward-facing floor-to-ceiling fifth-floor gallery windows—all sea, sky and skyscraper on a clear pre-spring day—the work instructs us in the ways of image making. How to Take Good Pictures is breathtaking and a little funny, but it’s also mournful and elegiac. Outside the picture windows we can see large scale excavations, which will make the way, eventually, for new buildings. In her Analogue series, a collection of pastel snapshots document the vanishing landscape of mom-and-pop shops and expand to reflect on the global rag trade. The results are a form of poetry, the sort of thing that cannot be summarized. They are miniature vitrines, diamond sharp.

Leonard’s photographs include the telltale black lines of analogue photo development, which indicate the edge of the exposed film. These lines point to the camera as a framing device, acting upon its subject rather than passively capturing it. In a 1997 interview with Anna Blume, Leonard expressed surprise that people think a photograph captures a real moment: “It’s not reality; it’s a subjective view. It’s a picture. I go out and I see things my way and take my photograph among all the millions of photographs that can be taken.” Leaving “the mistakes”—the dust, the borders, the holes—is a way of signaling to the viewer that the image is a product of labor, and that it was made by a person whose truth “is no more true than anyone else’s.”

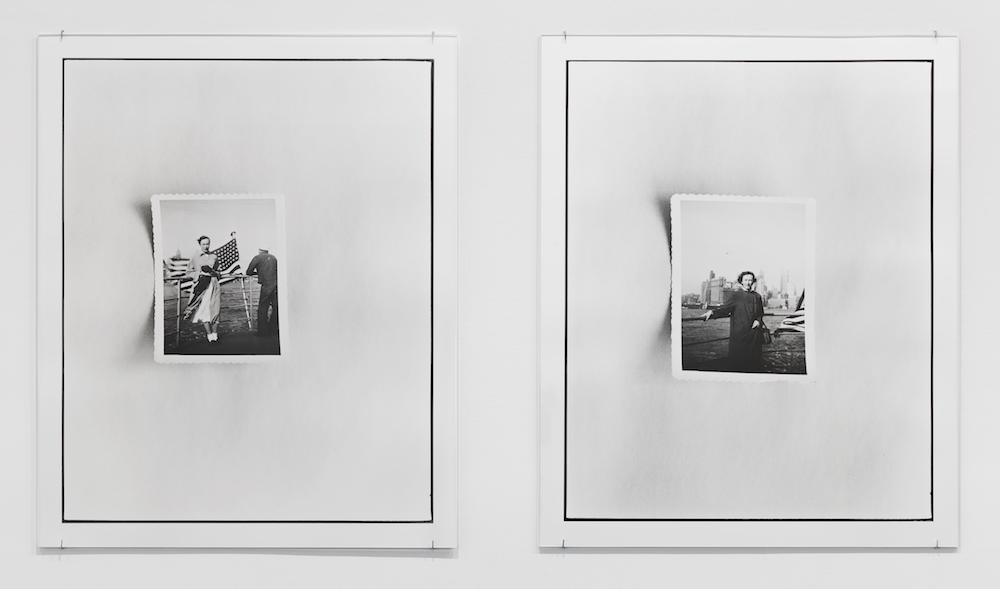

Zoe Leonard, New York Harbor I, 2016. Two gelatin silver prints, 21 × 17 1/8 in. (53.3 × 43.5 cm) each. Collection of the artist; courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York

Yet there is something special about Leonard’s truth. In his catalog essay, Bennett Simpson, who is one of the curators of the show, describes Leonard’s aesthetic as one of “subjective authenticity, sentiment, and sincerity.” Her sentiment-without-sentimentality spans her photography and her sculpture and ties her artistic practice to her work as an activist with ACT UP. As Leonard recounts in a 2010 oral history of the organization, she participated in “die-ins” and set up needle exchanges, which were illegal at the time. The needle exchange initiative was two-part: ACT UP enabled access to needles, and then, when activists were arrested and subsequently arraigned, they worked to set precedent for legalizing the exchanges. In the oral history, Leonard speaks of her mother, who had been involved in the anti-Nazi resistance in Poland, noting that “it was translated to me really early that you stand up for what’s right and do what you believe in at whatever the cost might be. That’s just what you do.” (Survey includes several images, re-photographed in the artist’s studio, of Leonard’s mother and grandmother arriving in New York Harbor.)

The AIDS crisis inspired one of Leonard’s most iconic works, Strange Fruit. The sculpture was made between 1992 and 1997, at the height of the crisis. It was inspired by the death of the artist David Wojnarowicz, a close friend of Leonard’s and the person to whom Strange Fruit is dedicated. Leonard attended her first ACT UP meeting on the day she found out Wojnarowicz was diagnosed. An update of the vanitas paintings of the old masters, Strange Fruit is a floor-display of emptied fruit peels—orange, banana, grapefruit, lemon, and avocado—held together with thread, buttons, and zippers. Decayed and dried, Strange Fruit is part still-life, part graveyard, part participatory artwork. It addresses the viewer as someone with a conscience, who can act against the tyrannies of silent, lethally complacent governments, but also as someone with a body that must eventually succumb to the realities of mortality.

Installation view of Zoe Leonard, Strange Fruit, 1992-97. Orange, banana, grapefruit, lemon, and avocado peels with thread, zippers, buttons, sinew, needles, plastic, wire, stickers, fabric, and trim wax, dimensions variable. Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased with funds

In The Lonely City, Olivia Laing writers that loss is a cousin of loneliness. Thinking of Strange Fruit, Laing suggests that “Physical existence is lonely by its nature, stuck in a body that’s moving towards decay, shrinking, wastage and fracture.” Strange Fruit¸with its titular reference to queer sexuality, as well as its invocation of Billie Holiday’s 1939 anti-racist protest song by the same name, is a work of personal politics. One imagines Leonard painstakingly sewing a banana peel, but then, one also pictures her attaching buttons: there is sadness here, to be sure—the fruitless attempt to avoid decay—but also something defiantly hopeful, a full-throated peal of laughter in the face of the plague. Strange Fruit speaks to fragility, to impermanence, but also to agency, and to the refusal to do nothing even when it seems there is nothing to be done.

My first significant encounter with Leonard’s work was during the 2014 Whitney Biennial, the last to be held in the museum’s former location on seventy-fifth street. For that show, Leonard transformed one of the fourth-floor windows into a projector, a form of camera obscura. Madison Avenue was projected topsy-turvy on the museum wall. It was immediately recognizable and completely strange, a world turned upside down but still alive.

Yevgeniya Traps lives in Brooklyn. She works at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study, NYU.

from The Paris Review http://ift.tt/2HDwme5

Comments

Post a Comment