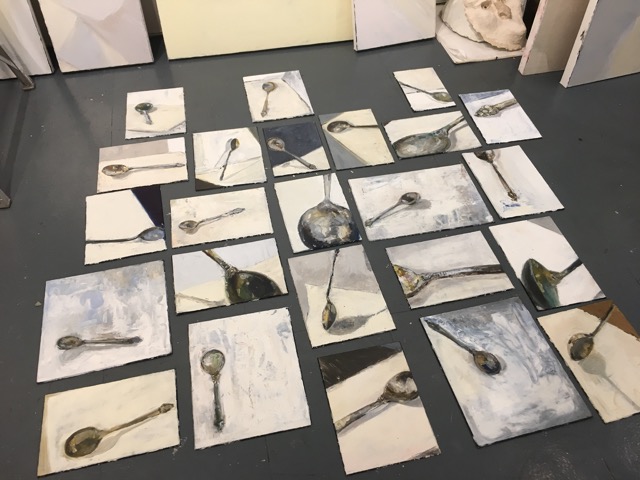

I was paying a studio visit on Jessica Anne Schwartz, a promising young San Francisco artist, early mid-career and recently transplanted to New York, and over in the corner, on the floor off to the side—she hadn’t particularly been intending to show them to me—she had ranged a series of small painted studies on board from several months back. She’d pulled them out earlier for the first time since she’d made them, across the last several months of 2017, and was trying to figure out what, if anything, to do with them. All images of a single spoon, from a wide range of vantages—“I’d first found the spoon abandoned out in a garbage pile on the street,” she explained —and in a tumbling array of alignments.

She and I gazed upon the assembled panels for a while, she leaning over, assaying a few other arrangements, sighing. “Single Serving,” was the name she’d assigned the entire set. Back then, she explained, she’d only just recently broken off from a longterm relationship, really only the second serious relationship in her life. Fresh out of high school, she’d married, that had lasted eighteen years, then she’d almost immediately taken up with this second guy, and that had lasted another eight, and that moment (in the middle of 2017) had really been the first time in her life she’d found herself living alone, all by herself. She’d gone into fierce mourning: this business of being all alone being all she could think about, that and, of course, how she was no longer with the latter boyfriend.

Somehow, she said, she identified with the spoon (a particularly poignant bit of projection, it occurred to me, given how the very essence of a certain kind of togetherness is the act of spooning, and in that sense, of course, of what possible use is a single spoon, lying there all alone?). So she painted the thing once, and then again, and then a third time, with ever an ever-growing sense of elation: she decided she’d paint twenty-four variations, ever more convinced that once she’d accomplished that, however long it took, she would be free of all this grieving once and for all.

And at first, she said, it seemed to work. She’d stayed up all night with the last few, painting away, and come morning, twenty-four panels filled, she’d walked out onto a transfigured street, as if entirely cured. The world outside looked as if she were seeing it again for the first time: clean and clear, all limpid and glistening.

As if: so it seemed. For, of course (she went on to recount), the next day the grieving came surging back once again. So much for the transformative power of art.

You know what they say, I commented: you may be through with grieving, but grieving is not through with you.

Yeah, she agreed.

For some reason I was put in mind of that marvelous old poem of Vikram Seth’s, “All You Who Sleep Tonight.” I took out my cell phone, googled it up, and read her the simple verse:

All you who sleep tonight

Far from the ones you love,

No hands to left or right,

And emptiness above –

Know that you aren’t alone

The whole world shares your tears,

Some for two nights or one,

And some for all their years.

She rocked herself as she listened, thrumming concurrence: she’d never heard that poem before. Where did it come from?

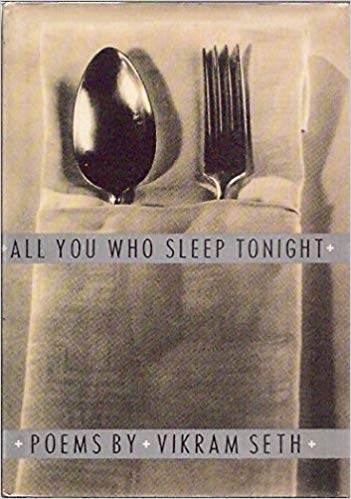

I continued to scroll down through the poem’s entry, to an image of the cover of the original eponymous 1990 collection in which the poem had been included, featuring a graphic that I imagined (clearly falsely, as things turned out) that I’d completely forgotten:

Lawrence Weschler, late of The New Yorker and director emeritus of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU, is the author of more than twenty books on myriad subjects. He is currently completing work on a biographical memoir of the years, during the early eighties, when he was serving as a beanpole Sancho to Oliver Sacks’s capacious Quixote, due out in 2019.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2KsQkgG

Comments

Post a Comment