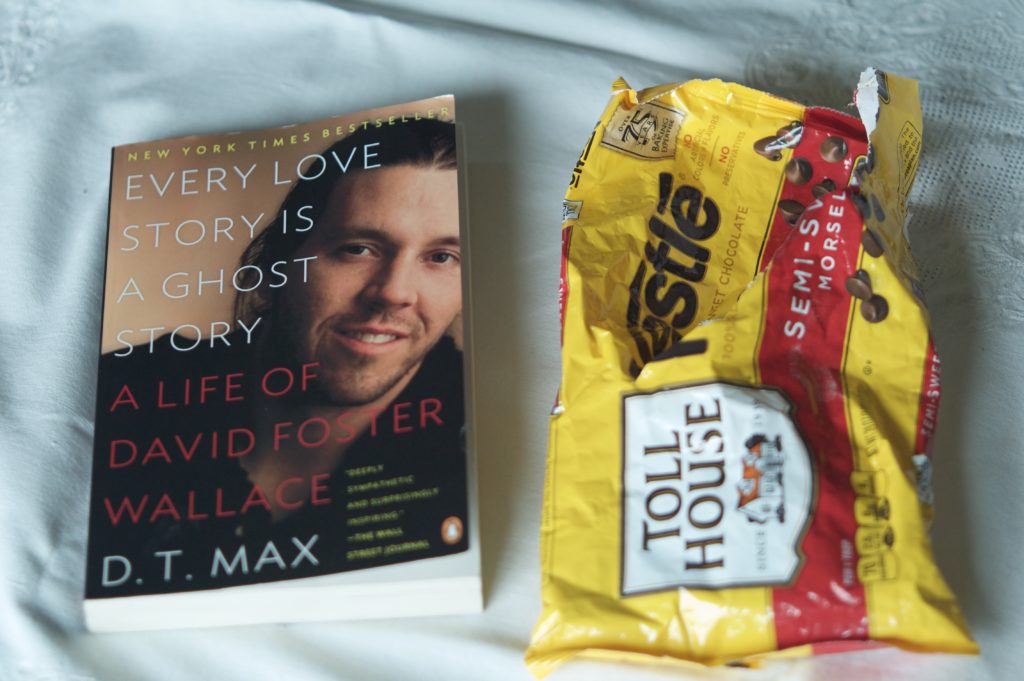

The writer David Foster Wallace (1962–2008) didn’t really eat food. When I met him, in 1996 when I was 23 years old, I really couldn’t cook, though it wouldn’t have occurred to me to consider this something we had in common. Wallace, who took his own life on September 12, 2008, ten years ago today, burst into fame in the late 1980s with experimental metafictions that took on the modern junk culture of advertising, celebrity, addiction and alienation through technology. He struggled with those entities himself, and was famous among his acquaintances for living mainly on packaged foods. Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, the excellent Wallace biography by D.T. Max, is littered with information like, “he lived on chocolate pop tarts and soda” or “he had a love of showering, Diet Dr Pepper and blondies,” or “there were only blondies and mustard in the fridge.” In 1995 journalist David Streitfeld saw a kitchen with little more in it than a case of Dinty Moore Beef Stew, and elicited the confidence from Wallace that “What’s really sick is I like to eat it cold.”

For my part, I was a non-cook to such an extent that my boyfriend, fed up with making meals for me, once angrily coached me through making him a dish he called “toaster oven pizza.” This involved an English muffin, a bag of grated cheese, and a jar of red sauce. I made it, but I thought he was being completely unreasonable.

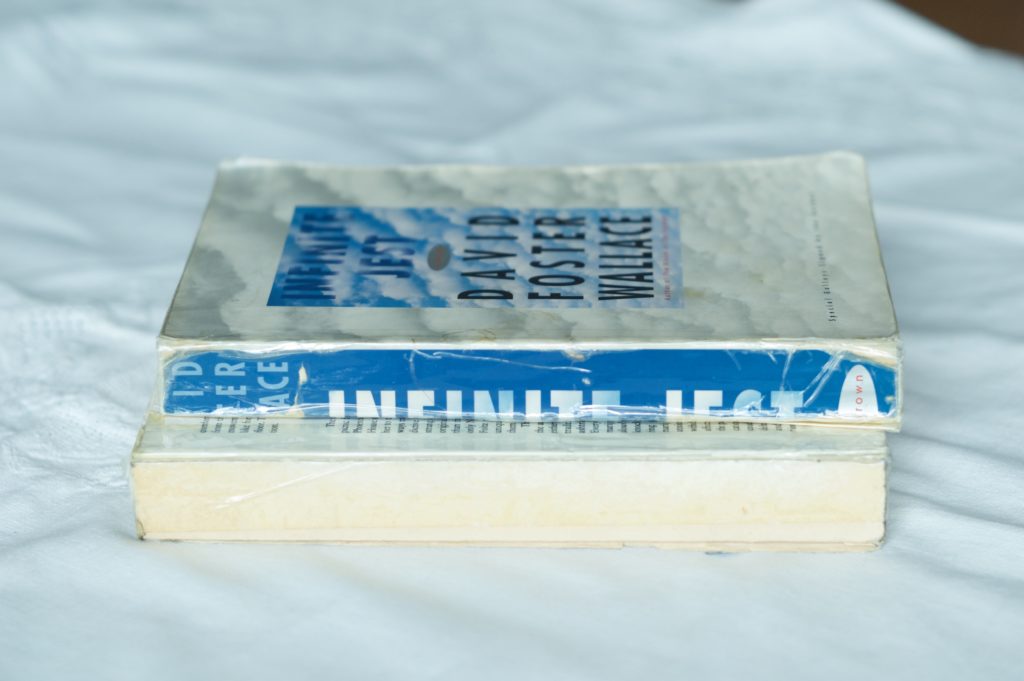

What I was mostly interested in back then was books and writing about them. I met Wallace because I’d transformed my dubious qualification of having read the advance proof of Infinite Jest twice into the opportunity to interview him during the book’s publicity tour. The interview ran on Stim, a newfangled kind of publication that in 1996 we called an “online magazine”. (That interview is still available online as part of the Wallace minor arcana and was just republished in August in an updated edition of Melville House’s The Last Interview series.)

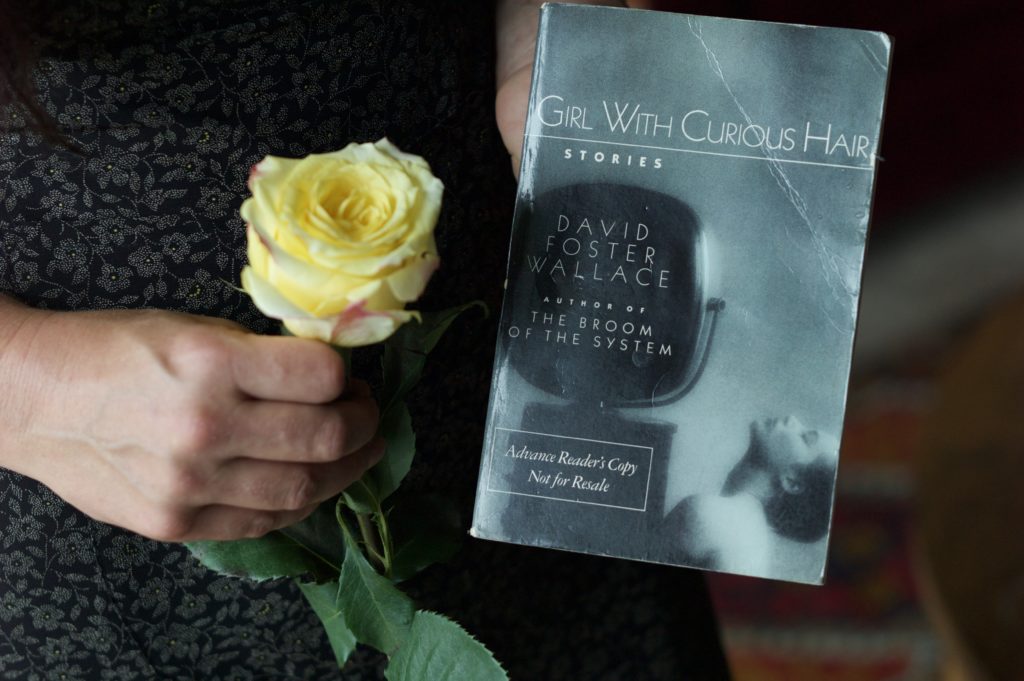

The writer-crush I developed on Wallace had come to me full blown when, one night reading alone in my first New York apartment, anxious and probably hungover, I sobbed my way through the end of “Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way,” the last story in the 1989 collection The Girl With Curious Hair. “Westward,” seen today with the jaundiced eye of adulthood, is a creaky metafiction about students in a fiction-writing class, whose plot, to the extent it has one, is about a road trip to a McDonalds ad-campaign reunion. The main character is Mark Nechtr, a sweet midwestern boy fiction-writer who is addicted to eating fried roses. Nechtr’s foil is a clever postmodernist girlfriend, who commits fictional suicide in the end (meta, complicated, story-within-a-story). Wallace later repudiated the story as “a horror show…a permanent migraine…crude and naive and pretentious,” but there was also a time when he felt it was the best thing he’d ever written. Max says that upon the story’s publication Wallace felt it was what he “had been born to write” and that it “said all he had to say.”

This is my signed advance reader’s copy of Infinite Jest, which could have been worth $1500 if I hadn’t ripped it in half to make it easier to carry around.

That anyone could cry over “Westward” is hilarious in retrospect, but truly, I did cry. The demographic of “young women seriously upset by postmodernism” must be vanishingly small, but in the mid 90s, it described me. I’d gone off to college with the squeaky overachiever’s excitement to discover the meaning of life (and then, you know, apply it to what came next). To my dismay, no matter what the subject was, its underpinnings were in French critical theory, which I understood to be a poised intellectual valueless-ness and destruction of meaning. This was embarrassing, and not the kind of thing one admitted to one’s friends majoring in semiotics, but it clouded my college experience in secret but real ways. Wallace, in “Westward,” seemed to get it. A bit of beautiful doggerel from the story, critiquing the seminal postmodern story collection, Lost in the Funhouse, by John Barth, has run through my head for the past 22 years.

THE DAY OF THE MOMENT WE’VE ALL BEEN WAITING FOR

For lovers, the Funhouse is fun.

For phonies, the Funhouse is love.

But for whom, the proles grouse,

Is the Funhouse a house?

Who lives there, when push comes to shove?”

Barth’s funhouse metaphor points to the infinite regression of the narrative viewpoint in fiction—even if you reveal the meta-story behind the story, you’re just adding another fallible and relative layer. None of it is real. On the contrary, Nechtr, the Wallace stand-in, “desires, some distant hard-earned day, to write something that stabs you in the heart. That pierces you, makes you think you’re going to die. Maybe it’s called metalife. Or metafiction. Or realism. Or gfhrytytu. He doesn’t know. He wonders who the hell really cares.”

In person, Wallace was polite and brilliant, and his answers consistently made my questions seem smarter, which was a huge relief. After the tape stopped rolling he asked me more about myself, and why I liked his work. He was pleased when I said my favorite story was “Westward” and asked if I was a Barth fan. I had to admit that I hadn’t yet read Lost in the Funhouse, at which point he said scornfully, “Then what did you like, the McDonald’s stuff?” I was forced to haltingly explain what I thought the story meant. At which point he said, yes, I’d gotten it, and seemed even more pleased. Eventually he gave me his mailing address in Normal, Illinois, and asked me to write him letters. Those who knew Wallace or who have read the Max biography, will be nodding their heads about now; he had a habit of availing himself of admiring young women, and his behavior has lately come under new scrutiny. The writer Mary Karr, with whom he had a relationship, has spoken out against him as recently as May, 2018.

That wasn’t my story with him, possibly because I never did write him. And when some days later, at the Infinite Jest launch party in New York City, he asked me to go back to his hotel room afterwards, I left the party early instead. I saw him once more at another party, months later (in the basement of a Two Boots pizzeria in the East Village, if memory serves)—and I avoided him, even though he followed me and tried to strike up a conversation when I went outside to smoke.

None of these lapses were because I didn’t like David Foster Wallace—on the contrary I liked him way too much. Looking back, it was an era when I just couldn’t do a lot of things. I couldn’t cook. I couldn’t write fiction. I had just embarked on an ultimately pointless mass-media career that I would never quite believe in. Very much like a Wallace character myself, I was a child prodigy frozen by adulthood, who drank too much and often wasn’t very nice to people. I let many opportunities slip by, and it’s no huge surprise that I flaked on an invitation to correspond with my literary idol, or that I fled from a personal relationship that I would have liked to explore. At the time, my best guess on how to fix the things that were obviously wrong with me was to read more books. Then, possibly, I could blame it all on Foucault.

Wallace never wrote another novel after Infinite Jest. The Pale King, published posthumously, was unfinished. I’m not sure how clearly it can be said that his struggles with the book contributed to his death, but any writer who has had a hard time finishing a book knows it’s not great for their mental health. Wallace once called “Westward” a “suicide note,” and I’ve found that prophetic. I’ve thought that he couldn’t, ever, quite, snip through the Barth Mobius strip—the clever and structural game-playing girlfriend he killed in the story was himself, and the beating and un-ironic heart he sought to somehow convey in fiction (the life inside the funhouse, if you will) was hard to find, and wouldn’t have been fun if he had found it.

In my meandering path towards a better adulthood, I kept reading books but stopped thinking that the theories found therein were going to answer the question of how to live in the world. I’ve come instead to the inelegant belief that pretty much the most important thing you can do with your day is make dinner, for your family or friends if you have them, or for yourself if you don’t. Do that, and the other stuff mostly falls into place.

I don’t know if Wallace ever learned to cook or to eat. By Max’s account he was happily married, so perhaps he did. In order to cook for him, as part of the on-going “Eat Your Words” column I’ve been doing here at The Paris Review, I couldn’t make my usual kind of food. I wanted to echo the fried roses from “Westward” by stuffing and frying edible flowers. I considered doing something with corn, as a nod to his midwestern heritage and lovely “Westward” quotes like “All we’ve seen is corn. Its been disorienting, wind-blown, verdant, tall, total, menacingly fertile.” Or “The corn is stunted right here a bit, and Mark’s view goes sheer to the earth’s curve: dark green yielding to pale green, to dark green, to just green….” But the man did not eat vegetables, so I couldn’t do either.

Instead I made blondies, which are just chocolate-chip cookie dough baked as a slab. I tried trendy brown butter and maple-pecan versions, and ended up with the classic recipe on the back of a Toll House bag, baked in a 9 x 9 pan for a satisfying chunky shape. The test batch, which I served at a children’s party, was the first dessert to vanish and I was surprised to see even the adults scarfing them down. Then I made a burger because Wallace liked them (well done) and featured them in both “Westward,” with its McDonald’s plot and in Infinite Jest’s WhataBurger tennis tournament. I made the burger as simply as possible on the stovetop, using a two-ingredient recipe and the brilliantly easy technique from Mark Bittman’s classic How to Cook Everything. I could have stopped there, but the table looked lonely, so I decided to return to that long ago classic and prove that I am now a person who can make a toaster-oven pizza without crying. It seemed like something Wallace might have eaten, or cooked, or appreciated. I tried various versions, including one with red sauce from a jar, but ended up with a ‘pizza’ using homemade three-ingredient red sauce lifted from a Marcella Hazan cookbook (not one of her official sauces, but the easier version she includes with some recipes). I spread the sauce on a baguette, with fresh mozzarella and a pinch of oregano. It wasn’t bad. I had one for lunch, and I cried again, a little, for David Foster Wallace, and for the young woman I once was. You are missed.

Mark Bittman’s Basic Burger

From, How to Cook Everything. Serves 4.

1 1/4 lbs ground chuck

1 tsp salt

-You want to handle the meat as little as possible. Shape it lightly into 4 burgers, about 4 to 5 inches across, sprinkling with salt as you do so.

-Preheat a large, heavy skillet (cast iron is best) over medium-high heat for 3 – 4 minutes; sprinkle its surface with coarse salt.

-Cook for 3 – 5 minutes per side, depending on preferred doneness.

-Serve on a bun, garnished as you like. I used a brioche bun, plus lettuce, tomato and bacon.

Toaster Oven Pizza

Serves 2.

2 tbsp olive oil

14oz can of diced tomatoes

2 cloves of garlic, minced

1/4 tsp salt

3/4 cup fresh mozzarella cheese, chopped

dried oregano for topping

2 5-inch lengths of baguette, cut in half

-Heat the olive oil in a skillet on medium-high heat. Add the minced garlic and fry, stirring frequently, until the raw edge is off and the garlic is fragrant and beginning to turn golden, about 90 seconds. Add the can of tomatoes, stir, and turn down to a simmer. Cook for 10 to 15 minutes, until the sauce has reduced to a fairly thick paste.

-Spread each baguette length with 2 tbsp sauce, topped with 2-3 tbsp of mozzarella cheese and a pinch of oregano. Toast and serve.

Chunky Toll House Blondies

Adapted from the recipe on the back of the Toll House bag.

2 1/4 cups flour

1 tsp baking soda

1 tsp salt

2 sticks butter, softened

3/4 cup granulated sugar

3/4 cup packed brown sugar

1 tsp vanilla extract

2 large eggs

1 1/2 cups Nestle Toll House Semi-Sweet Chocolate Morsels

1 cup chopped pecans

-Preheat oven to 375. Butter a 9×9 inch baking pan.

-Combine flour, baking soda and salt in a small bowl. Beat butter, granulated sugar, brown sugar and vanilla extract in a large mixer bowl until creamy. Add eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition. Gradually beat in flour mixture. Stir in morsels and nuts. Spread in the pan, and bake for 25-30 minutes, until the crust is golden and the center is set.

-Cool before slicing and serving.

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York.

Read earlier installments of Eat Your Words here.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2x5p5kn

Comments

Post a Comment