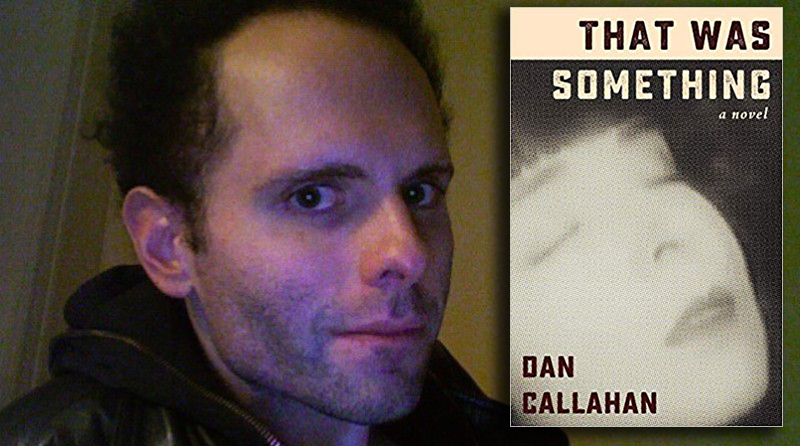

Dan Callahan lives in a two-story brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn. He and his partner, Keith Uhlich, write about films, and their home is a museum of the moving image. Pictures of Liv Ullman, Ingrid Bergman, and countless others adorn the walls, and film history books cram the bookshelves. Callahan himself has written biographies of Vanessa Redgrave and Barbara Stanwyck, as well as The Art of American Screen Acting, 1912-1960. This October, Squares & Rebels released his debut novel, That Was Something.

There’s a great deal of Callahan in the novel. The protagonist, Bobby, is an NYU undergraduate cinephile, as was Callahan himself. But the star of the book is Monika Lilac, a glamorous woman he meets at a screening of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Cronaca di un amore. Everything about Monika is stylized, including her name, taken from her favorite silent picture, Lilac Time (1928). She holds legendary silent film parties in her apartment (talking prohibited), and encourages everyone to talk less, especially in love. Every outfit and utterance from Monika is memorable, even when she misfires; she embodies Oscar Wilde’s aphorism, “The first duty in life is to be as artificial as possible.”

Bobby’s best friend, Ben Morrissey is a photographer, a Don Juan charmer, and a heterosexual. He’s also the love of Bobby’s life. The problem of sexual orientation complicates a painful romance that is both reciprocal and unrequited. Their friendship takes detours into places of euphoria and heartbreak, and the only thing that never changes in the book is the cinema. Films populate That Was Something the way that characters might another novel. Even the towering persona of Monika Lilac pales in the light of the silver screen. The novel begins: “I was looking for the keys to the kingdom, and I found them or thought I did in Manhattan screening rooms, in the half-light and the welcoming dark.”

After a walk-through of his home, Dan and I spent a rainy Sunday afternoon in his dining room talking movies, literature, and his foray into fiction. A photo of Marlene Dietrich, signed in gold, presided over the conversation. Callahan imbibes a lot of coffee and speaks rapidly, always on the verge of an insight. His eyes are wide, as if the theatre lights have just gone down.

INTERVIEWER

There’s so much fabulous film memorabilia in this house!

CALLAHAN

That’s the lobby card of Margaret Sullivan’s last movie. When I was a kid, my parents would go to the autograph shows at the Holiday Inn and I would go with them. And Joan Crawford is up there! That was given to me for Christmas. Imagine Christmas morning, the most wholesome holiday in the calendar.

INTERVIEWER

OK, let’s really dive in. Now don’t be alarmed, this is not a tarot reading. I put my questions on notecards.

CALLAHAN

That delights me. You know why? Because it’s orderly. I like order. Maybe a little bit of disorder, but in an orderly way.

INTERVIEWER

Yes, I sense that in you. You studied acting at NYU?

CALLAHAN

Yes. I went to NYU to study at the Stella Adler conservatory for two years, and then I did experimental theater for a year.

INTERVIEWER

That Was Something is dedicated to Jessica Lange. What is her significance to you?

CALLAHAN

Well it’s notorious in my family that when we went to Disney World, the first day that we were there, I didn’t want to leave the hotel room because King Kong was on. I just was very taken with her. I didn’t want to go out to the rides, I just wanted to stay in and watch Jessica Lange. Then when I was in high school, and just miserable in many ways, I saw Francis, and I became obsessed with that film. Now people use the word ‘obsessed’ entirely too much. They shouldn’t use it unless they really mean it. I can use that word with that film. Do you know Francis Farmer? Her story? She was a thirties actress. She had a great deal of promise. She was put into mental institutions, and the way the film plays it, she was persecuted. The reality is more complicated, and the film gets a lot of things wrong. I didn’t know that as a teenager. When I found that out as an adult, it was a great relief to me. Francis, I identified with her. I behaved very melodramatically. Which seems absurd to me now that I did. But Jessica Lange — I love that her emotions are like events. She gets angry in a way that is like chocolate cake. If I could have I would have made her up. The way she looks. The way she talks. The way she puts a hand to her sternum. In Blue Sky she’s got this red dress on, and she’s making a scandal of herself. She’s got her hair up and the camera’s on her back. She’s got a very broad, muscular back. She’s acting with every joint of her body. It’s like a great dancer.

INTERVIEWER

In Brooklyn magazine, you wrote, “Jessica Lange doesn’t play the words, but the actions and emotions in the text.” And then you said: “If you didn’t know English at all, you could still love her performance in Long Day’s Journey into Night.”

CALLAHAN

Yes. I have to say, that’s very Stella Adler. We were always told, “Don’t play the words, play the action.”

INTERVIEWER

What you wrote about Lange makes her seem like the ideal silent film actress. Your heroine, Monika Lilac, is obsessed with silent films. Would she approve of Jessica Lange?

CALLAHAN

Probably in the same way that I do. I think that Monika contains multitudes. Monika can play-act at being practically anything. The thing I wanted to suggest, also with Ben Morrissey, is you’re only getting what the narrator tells you about them. There are things about them that the narrator doesn’t know, and that I, the author, don’t know. How old is Monika? Where does Monika come from? How does Monika earn her living? There are so many questions with her. Is she basically a lesbian? Or not? Is that even germane? And then that, of course, gets into the question of the sexuality of Ben and Bobby.

INTERVIEWER

So many gay guys at that age get a straight boyfriend who’s just like Ben.

CALLAHAN

That’s a fascinating subject, because no one ever talks about that!

INTERVIEWER

But it’s so common. Though it usually doesn’t go as far physically as it does with Bobby and Ben.

CALLAHAN

I pushed it a little bit because I wanted to see what the parameters were. Usually in life, you don’t find out. I wanted to see what would happen. From my point of view when I was writing it— and people reading it might have a different interpretation— Ben Morrissey is heterosexual.

INTERVIEWER

I concur with that. It happens usually when you’re between the ages of 17 and 19 where you’re a young a gay male and you become best friends with a straight male who is fully aware of the sexual undertones in the friendship and exploits it either for ego reasons or something else.

CALLAHAN

It’s easier now than when I was young, hopefully. However, [at that age] you’re in school. And school to me was like a kind of prison. You are stuck with whoever is there in school with you. All your hormones are exploding. And if you’re gay, you aren’t going to be around your own kind much. You’re going to be with heterosexual males, and so what’re you supposed to do? Are you supposed to say, well they’re heterosexual so I’m not going to try? Of course not! You’re alive. You have to try. And you’re going to break your heart and you’re going to cause a lot of trouble and you’re going to cause a lot of trouble for him, god knows, the straight guy. It’s a great field for drama. I think Ben Morrissey wants to behave honorably. How do you do that? It’s difficult. Though someone else reading it might ascribe darker motives to him. Ben can’t get an erection for Bobby. I don’t think it’s too extreme to say that that’s tragic. Or at least very sad.

INTERVIEWER

Yet in the ending of the novel, I don’t see despair.

CALLAHAN

The ending was very different from the way I originally wrote it. This ending was written fairly recently. My publisher said, “I think you should write another ending.” I knew that he was right. The ending that I had was somewhat sentimental. I’m Irish. I’m drawn to sentimentality. And yet, I know very well that sentimentality is fattening, and it’ll give you a heart attack. When I was writing the ending of this novel, I thought, “You need to make it hurt.”

INTERVIEWER

Susan Sontag wrote in her journal that any stories she wrote should result in her “trembling” should be a “scream,” and make her heart start pounding.

CALLAHAN

She would hate me saying this, but that sounds a little camp-y.

INTERVIEWER

Back to Monika Lilac. I think that she casts a very necessary, unreal quality onto the book. I think that all art needs something of the unreal. The basic plot of this book is plausible, but the unreal quality that makes it pleasurable is Monika’s character.

CALLAHAN

I hope it’s in the tradition of a homosexual male writer writing about a larger-than-life female character. Christopher Isherwood and The Berlin Stories, Truman Capote, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, those are the two most famous examples. I think that that should be celebrated. If the heterosexual male writer met Sally Bowles or Holly Golightly and wrote about them, it would be a very different kind of book, don’t you think? It would be pretty unpleasant.

INTERVIEWER

Have you known a lot of women like that in your life?

CALLAHAN

I have. I don’t know if I’m drawn to them or they’re drawn to me, maybe both. Larger than life women, women who are outside the mold. I’m drawn to that in men too. I’m drawn to larger than life people so that I can be a foil to them. My friend Nick Moore is like that. He’s this great heterosexual guy in New Jersey. Enormous charisma, enormous vitality — I love people like that. Because I don’t particularly have that, but I can come alive if I’m around it.

INTERVIEWER

You’re very alive yourself.

CALLAHAN

Not all the time. When I’m stimulated, I can be stimulating, but there are long periods when if I’m not around it I go underground. I’m in my room there in my own world. I don’t go out enough, I don’t talk enough with people. I should do a little more of that.

INTERVIEWER

When you were writing the novel, and constructing the narrative, the structure, the scenes — were films or literature more influential to you?

CALLAHAN

Everything with me is the cinema. I live, eat, breathe, fuck the cinema. Film. Keith, my partner — that’s our thing. Obsession is a mild word for what it is. Influence on the novel — of course the answer is the cinema. My whole life is influenced by the cinema. I describe many silent films in the book. I chose silent film because it is entirely visual. It’s all fantasy, all imagination. Monika says romance is so potent in silent films because there’s no talking. It’s like a trance.

INTERVIEWER

How much of your early sense of what desire and sensuality feels like came from movies?

CALLAHAN

Now that’s interesting, because I should say all of it. Yet honestly, I think I had to make it up as I went along. Because as I was saying there weren’t gay guys in movies when I was a kid.

INTERVIEWER

Only coded ones.

CALLAHAN

Yes. So sensuality, eroticism, that’s a life thing. I didn’t get it from the cinema. The cinema and eroticism to me, it’s like Bobby and Ben, it’s so near and yet so far. You can’t get much of it from the cinema. Though a novel, you can. Something like James Salter’s A Sport and a Pastime, that’s much more erotic than any film I’ve ever seen, precisely because it’s all in the head. What is sex and eroticism? If it’s any good, it’s all in the head. Older people would say, yes, I saw Lana Turner and John Garfield in The Postman Always Rings Twice and that’s how I learned how to kiss and all that kind of thing. For some reason when there was less overt sex it was more erotic. Once we get to all this ‘everybody’s naked, everybody’s doing whatever’ on the screen, it’s too much. It’s too much! My experience has been, I don’t want to see a dirty movie. But I do want to read a dirty book. There needs to be some kind of mystery, enigma. I think people should read James Salter instead of watching hardcore pornography.

INTERVIEWER

Speaking of pornography, even though the Internet is in That Was Something, with Monika’s websites and a few email exchanges, there’s a very pre-Internet feeling to the book because it’s so landmark and place-based. Washington Square, Caffe Reggio, Anthology Film Archives…

CALLAHAN

I once went up to Jessica Lange at her photography show. I had to drink. In the pre-Internet era, that’s partly why I had to drink. I could never have gone up to Jessica Lange and talked about her photographs if I hadn’t availed myself of the wine there. Probably people drank more pre-Internet.

INTERVIEWER

It’s true, to be rejected online is nothing.

CALLAHAN

Nothing! Bobby has to go to bars and talk to men. He doesn’t specify what’s said to him but at one point he says they said cruel things to [his] face. Pre-Internet… there’s no reason to be nostalgic for that. People say “we’re so disconnected now.” Good! Thank god.

INTERVIEWER

It’s hard to imagine Monika being that interested in contemporary films. And Monika may be a little part of Dan Callahan in drag. But you continue to review new films and write about them all the time. What is it that keeps you interested in new movies?

CALLAHAN

We were talking about being gay and in school and you’re with these straight guys. Me writing about contemporary films — it’s like, what, am I not supposed to go after the straight guy? It’s exactly the same thing. It’s because I’m alive.

Ben Shields is a writer, journalist, and teacher. He lives in Brooklyn.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2RRPj1O

Comments

Post a Comment