While aiming a lens at my face, the photographer whispered, “You’re striking.”

This quality lives far from pretty. Daisies are pretty. Adolescent hamsters are pretty. William Wordsworth wrote pretty poetry. It wasn’t striking. Striking poetry ambushes us. The sensory details are chosen to paralyze, discomfit, or inflict pain. When such poetry bears lilies, they fester. When such poetry harbors horses, they crush toes. When such poetry casts a fishhook, its metal sinks into an open eye.

Striking phenomena resemble beautiful ones in their force and strength. “Beauty quickens,” said critic Elaine Scarry. “It adrenalizes. It makes the heart beat faster. It makes life more vivid.”

When I was a ten-year-old tomboy, I asked my father, “Why does evil exist?”

After looking up from his watch, he replied, “Myriam, imagine how boring life would be if evil didn’t exist.”

It makes life more vivid. At the time, my father’s authority on the matter went unquestioned. In hindsight, his answer strikes me as slapdash, dangerous, and wrong.

When I was older, I lived with a man who, though he was evil, was as boring as he was dangerous. Here is an inventory of his pastimes: plucking bass guitar while buzzed, extolling the greatness of soccer player Lionel Messi, and misogyny.

He turned me into a human soccer ball, and yet I couldn’t recognize what was happening. The radical feminist Andrea Dworkin experienced this same perceptual inability, explaining that the horror of what is happening to a battered woman exists, “quite literally, beyond her imagination.” My mind could not name what he did to me. Misogyny struck me dumb.

The first time it happened, we were standing together in the dining room. I tapped his shoulder. “Quit it,” he snapped.

Playfully, I tapped again.

He twisted and his fist punched me hard enough to make me gasp and reel.

“You hit me!” I declared.

“You started it,” he accused.

Confusion took over. My arm throbbed.

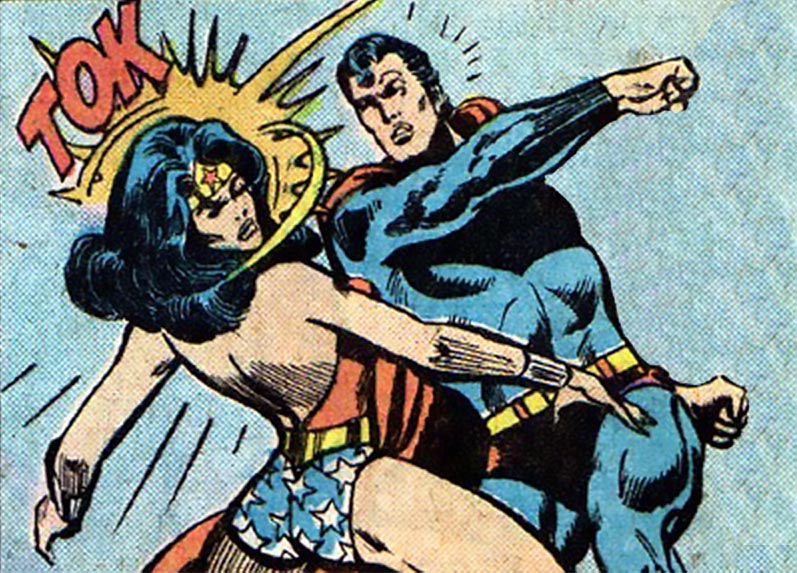

I’d seen men raise fists at women in cartoons but those caricatures hadn’t prepared me for how it would feel. The cartoons never revealed the punching bag’s interiority, her sense of shock that cedes to disbelief. How can it be that the man who brought you sunflowers, grilled salmon for you, kissed your eyelids, and admired your baby pictures is the same person now turning you purple?

Incredulity seduces. It makes us succumb to the fallacy that the world is just, that the violence we receive must be merited. When we confide in others about what happened, they often indulge in this, too. It satisfies our appetite for order. Our horror is wallpapered over with karmic perversion: people who deserve bad luck get it.

Weeks before I left this man once and for all, he stood in the middle of the living room. Folk music played.

“Dance with me,” he ordered.

His command wove a catch-22. If I danced, he’d mock me, comparing my movements to a “retard’s.” If I declined, a painful or degrading ambush would likely occur. I said no.

Batterers are allergic to women’s noes. He persisted, begging, and I knew he wasn’t going to relent until I danced with him. I joined him and swayed. He shimmied, twirled, and said, “Do what I’m doing.” I mimicked his movements. As my muscles relaxed, a blur sailed at my face.

It stung, stunning me.

“You slapped me!” I said.

He bristled. His face grew stern. “It wasn’t that hard.”

I tingled with fear and disgust. Underneath that, I felt rage. Through clenched teeth, I said, “It was hard enough.”

His nostrils flared. He scowled. Glaring, he repeated, “It wasn’t that hard. I know because I hit you.” He puffed up like a rooster ready for a cockfight. He pointed at his cheek and ordered, “Hit me as hard as I hit you. If you hit me harder, you’ll get it worse.” His other hand made a fist.

In a striking display of defiance, I hissed, “I’m not going to hit you.”

I knew better than to even glance at the door.

The last time I’d made a run for it, he had, among other things, suspended me by the head and strangled me. You might think me stupid for having stayed. If you think so, you misunderstand that survival doesn’t always belong to the fittest. Sometimes it belongs to the most patient. You see, this man had shown me he’d kill me for leaving him. That’s what strangulation is, a death threat. The cost of my emancipation was too high, and my fear made his violence effective. I felt his hands around my neck even when they weren’t there. I wore their memory like an invisible dog collar.

From an ignorant distance, the choices battered women make to survive might strike observers as ridiculous and self-defeating. The philosopher Albert Camus traced the contours of this misinterpretation when he wrote, “The absurd is lucid reasoning noting its limits.”

Post-strangulation, I struck a deal with myself: Stay with this man in order to stay alive. Wait. Plan. Get out once he leaves a metaphorical door ajar.

The verb to strike comes from Middle English. It meant “to stroke” before it came to mean “to deal a blow.” I read the Middle English classic The Canterbury Tales in college. Back then, the only person who’d ever slapped me was a woman, my mother. I admired a brash Chaucer character who’d also been hit, the wife of Bath. Jankyn, her husband, entertains himself with story after story about the “wickedness” and “wretchedness” of women, and the wife tires of his misogynist pastime. She retaliates by ripping a single page from one of his books. For her vandalism, Jankyn raises his and hand and “[strikes his wife] … deef.”

From across the centuries, the wife of Bath, struck deaf for destroying a man’s pleasure, beseeches: “If women hadde written stories, / As clerkes han withinne hire oratories, / They wold han writen of men moore wickednesse / Than all of the mark of Adam may redress.” It’s in honor of the wife’s daring hand that I tell the story of my face, my face that has been struck and strikes. I no longer feel hands around my neck. “You’re striking,” the photographer says. I exhale, I face the lens, and refuse to smile.

Myriam Gurba is the author of Mean, a nonfiction novel and memoir. She lives in California and loves cash, succulents, and the elderly.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2KDwwrF

Comments

Post a Comment