Nina MacLaughlin’s six-part series on the sky will run every Wednesday for the next several weeks.

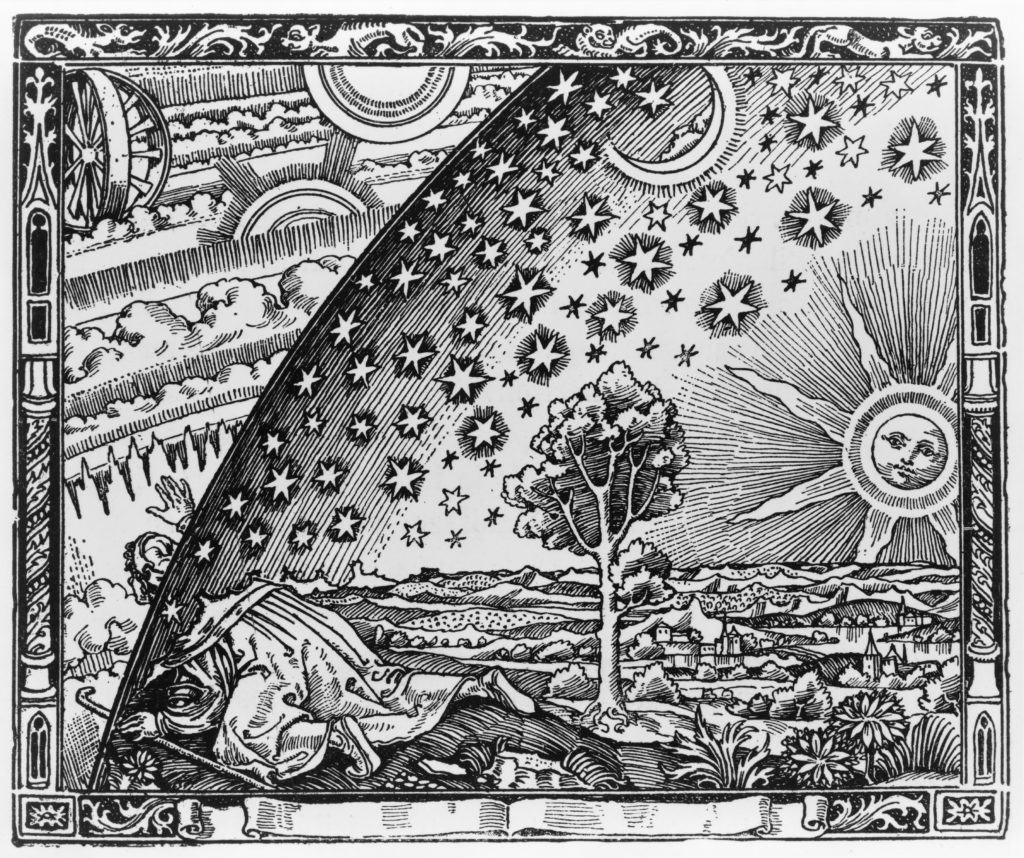

The Flammarion engraving, unknown artist. First appeared in Camille Flammarion’s L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire (1888)

Rare right now, the airplanes. Before, the planes taking off from Logan tracked a path I saw from my pillow in bed, high lights wing-blinking in the night sky in ascent from Boston. Not anymore. Not for now. Before February of this year, the planes blurred into the texture of the everyday, cigarette wisps of contrails, skyheight roar, as regular as the honking geese by the river, which sometimes I notice and sometimes disappear into the familiar static of any afternoon. Now, I see an airplane and think: who’s going anywhere? And why? Then I remind myself it could be cargo, small packages, love letters. To see an airplane now is to be aware of both presence and lack: oh, look, there one is; oh, gosh, I notice because they’ve been mostly gone. And then comes the press of knowing, the weight across the chest, the reminder why.

The gravity of knowing. “The more you know the more you think,” Anne Carson said recently. And the more you think the more you question. What are we supposed to know? What’s better sensed than understood? What happens when the gravity of knowing threatens to tear apart and upside-down the way the world has existed for you? Do you run away?

I pursued some knowing recently, and regretted it. The amount of feet in a mile is a number that’s never stuck with me. I asked a distance calculator to convert 35,000 feet—classic airplane cruising altitude—into miles. When it delivered the answer—6.6287879 miles—I thought, I’ve made a mistake, or it has. This cannot be. Six point six miles up into the sky?

If I were to take a 35,000 foot walk, I could leave my apartment, head more or less due south, and in a little over two hours, reach the Franklin Park Zoo. Two hours on foot and I could look a tiger in the eye. Seems like dreaming. (It’s not an option now: the animals are all locked in.) But 6.6 miles up? It is a fact I wish I could un-know. It disrupts my comfort. Am I initiating some of you into this distress? If I suffer in knowing, does it mean you ought to as well? You can forget I said anything.

When you dream of flying, do you have wings? To take flight in dreams is an experience of uplift, of thrust, an unburdening of weight and an entering into the voluptuousness, as Gaston Bachelard calls it, of the soar. We’re bathed in the pleasure of defying the pinning laws and drinking in new views. Freedom! Lift! A human impulse, a shared experience in our dreamlife, to move as seagulls, petals on wind, superheroes, gods. “Dreamtime,” writes poet Nathaniel Mackey, “is a way of enduring reality . . . It is also a way of challenging reality, a sense in which to dream is not to dream but to replace waking with realization, an ongoing process of testing or contesting reality, subjecting it to change or a demand for change.” How high can we go? How free can we get?

When I fly in my dreams, I don’t have wings. And usually I’m not lifting off the earth, but falling first, and instead of crashing to my bone-crushed death, I sweep above the surface. The relief! The thrill of not ending, of avoiding the crash, of there being more to see, more to know. The relief of an altered arrival. As Mackey writes:

It was Arrival

we were

in, suddenly so with a capital A, all

we’d

always wanted it to be, been told it would

be . . . Falling from the sky, an immaculate

dust

attending

sleep

Does an ultimate landing place exist? Or are we always arriving, always Arriving, falling, faltering, flying, to land once more, then fall again? Our dreams offer glimpses of what could be, visions that can change what we know and how we exist in the waking world where we live. We fall asleep, sink into our dreams, and rise, ascend, Arrive, wake up.

Poet Éireann Lorsung writes also of arrival:

We are flying

machines we cannot land.

One night, I dream

of loving you; another, of falling

without ever coming to earth—the same dream.

Falling without end, machines we cannot land, here we are, immaculate dust, and we are all hurtling—towards what?

Last year, scientists captured the first photograph of a black hole, “a monster the size of our solar system,” according to a recent article in the Harvard Gazette, “that gobbles up everything.” Black holes are “the epitome of what we don’t understand,” said a Harvard physics professor named Andrew Strominger. “And it’s very exciting to see something that you don’t understand.” It is exciting. It lifts us right off the earth. One person I know refused to look at the photograph, because he felt to lay eyes on it would bring curse. Some things, he said, should remain a mystery. Another friend admitted recently that seeing women in masks was turning him on. Something akin to the Victorian titillation of a revealed ankle?, I wondered. Octavio Paz writes of “the rotten masks that divide one man / from another, one man from himself” and how when they crumble “we glimpse / the unity that we lost . . . the forgotten astonishment of being alive.”

The physicist Strominger admits that he wept when he saw the photograph of the black hole, and then he asked, “What can we learn from this?” What’s there to be found? How far can we go? He and the team looked at the rings that surrounded it. “Their individual brightness, thickness, and shape depend on the monster’s manipulation of its surrounding geography.” And here, the article notes, is “where things get stranger: A black hole hoards images of the past.” Bits of light that escape the ring “carry a reflection of what the universe looked like when they entered the black hole’s pull.” Another physics professor, Joseph Pellegrino, describes it this way: like watching “a movie, so to speak, of the history of the visible universe.”

I do not understand. I do not understand. I kneel down and raise my hands to the sky in non-understanding. I hear phrases like the anticenter of the galaxy and my brain lights on fire with the excitement of non-understanding. In the article on black holes: the word monster, the word hoard, the word inferno, the words gobbles up, and I understand these words, and the imaginative flight required to make sense—there’s no making sense!—of a light-eating gravity-bending nothing. The language of dream is used, of children’s stories, of comic books, of myth, of the poetry that grants us closer access to our non-understanding and the awe of the incomprehensible. “We take part in imaginary ascension because of a vital need, a vital conquest as it were, of the void,” writes Bachelard. “Our whole being is now involved in the dialectics of abyss and heights. The abyss is a monster, a tiger, jaws open, intent on its prey.”

We rise up, take mental flight, we lift ourselves six point six miles into the sky, and higher, and higher, to conquer the void. But as we rise to conquer, guess what? We’re also moving towards it. See it as threat, as horror, see the abyss as a force that will split you, rip you apart, eat all your thoughts and evaporate your bones. It is, and it will. It’s up to us, how close to get. Up to us, how much we want to know. What does the tiger’s breath smell like? What’s it feel like to stand on a doughnut of light peering in to the nothing we can’t escape? The physicists at Harvard call the center of the black hole “the prize.”

There is always further to go. Even if we reach the end of the universe, there is still an after-that. We’ll keep ascending in machines we can’t land, moving towards the moment when the masks crumble and we glimpse the unity we thought we lost. It’s here to be found. Know more, think more, ask more, listen. Rise, fall, fall again, fall better. With each inhalation, we take the sky into our lungs. We exhale the dropletted matter of life and death. Haven’t you become more aware of your breath? Felt it compromised by the soft cloth in front of your face? Inhale now. Take a big skyful into your lungs. What luck. Here it is: the astonishment of being alive. And the responsibility. What can we learn? What can we do? What’s here to be found? What’s the prize at the center? We don’t know. The experts don’t know. No one knows. No one knows what happens next. “Sweet is it, sweet is it / To sleep in the coolness / Of snug unawareness,” writes Gwendolyn Brooks. We’ve been locked inside like the tigers, listening for the roar of the planes, wondering about the earth that we’ll return to, or when we will, or if. Through our un-knowing, we re-emerge into the world, out of the sweetness of sleep, stumbling—and soaring—out of our dreams, and taking them with us, not just to endure reality, but to challenge it. To demand that it change in the ongoing Arrival of our waking.

Read earlier installments of Sky Gazing.

Read Nina MacLaughlin’s series on Summer Solstice, Dawn, and November.

Nina MacLaughlin is a writer in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her most recent book is Summer Solstice.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2ZNfUmd

Comments

Post a Comment