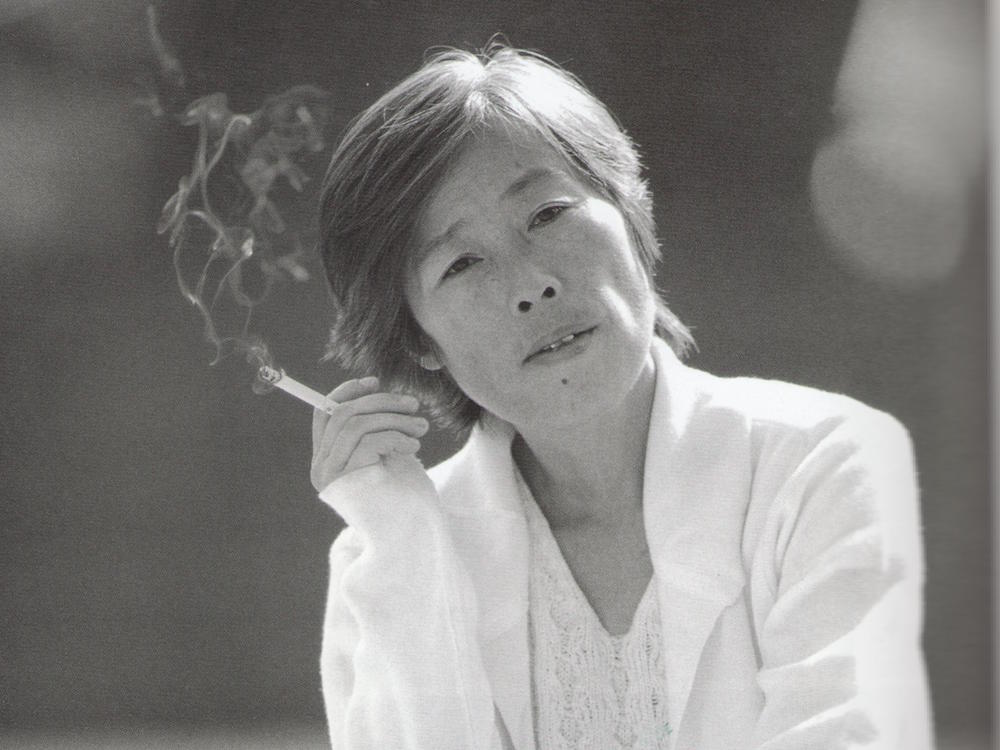

Choi Seungja is one of the most influential feminist poets in South Korea. Born in 1952, Choi emerged as a poet during the eighties, a turbulent and violent decade that saw nationwide democracy movements against the authoritarian government. During that era, South Korean poets were predominantly populist, writing “people’s poetry” that protested authoritarian rule. These poets were also mostly men. But during that time, a new wave of feminist poets emerged, such as Kim Hyesoon, Ko Jung-hee, Kim Seung-hee, and Choi herself. When Choi first started publishing in 1979, her provocative poetry was dismissed by the male literary establishment who expected women to write quiet, domestic poems. As the translator and poet Don Mee Choi writes in the anthology Anxiety of Words, Choi’s language and content were “attacked for being too rough and vulgar for a female poet.”

Born in the small rural town of Yeonki, Choi Seungja attended Korea University, devoting her studies to German literature, and afterward made a living as a translator of German- and English-language books. In 1979, she was the first woman poet to publish in the prestigious journal Literature and Intellect. Despite her growing success as a poet over the following decades, Choi mostly lived alone in near poverty. In 2001, she experienced a mental illness that kept her in and out of hospitals. A community of poets came to her financial aid; the poet Kim Hyesoon, for instance, collected money each month to support Choi, and the press Munhakdongne gave her a writing space in their office so she had a place to write and translate.

Choi’s stripped-down poetry is breathtaking and frightening. Her poems are uncompromising because she will stare into the infinite dark tunnel of her solitude and not break that stare. She writes, with terrifying alacrity, the existential despair of living in a hierarchical society where free will is a joke. While it has been changing, South Korea was a paternalistic and Confucian society, where the individual was subsumed by their family unit, especially for a woman, whose worth was measured by her husband and children. When a woman marries, her name is no longer used. She is called “so-and-so’s wife” or “so-and-so’s mother.” Because Choi was a single woman, she was an aberration. The I in her poems is often abjectly alone. The phone in her home is so silent day after day that when it finally rings, she is frightened. Instead of the timeline of a traditional Korean woman who measures her milestones by marriage and children, she has only death to shadow her as she ages. In her poem “Thirty Years Old,” Choi writes, “Death’s traffic light blinks red / in my two eye sockets / my blood is jelly, my fingernails sawdust, / and my hair wire.” In the poem “Already I,” Choi contends:

Already I was nothing:

mold formed on stale bread,

trail of piss stains on the wall,

a maggot-covered corpse

a thousand years old.Nobody raised me.

I was nothing from the beginning,

sleeping in a rat’s hole,

nibbling on the flea’s liver,

dying absentmindedly. in any old place.So don’t say you know me

when we cross paths

like falling stars.

Idon’tknowyou, Idon’tknowyou,

You, thou, there, Happiness,

You, thou, there, Love.That I am alive

is no more than an endless

rumor.

Metonyms of the body as waste pervade her poetry: the piss, shit, and vomit that the body rejects and that we recoil from because the emissions remind us of our own mortality. The barren womb is also a central motif, evoking the disgrace she feels as a childless woman in a society where a woman is the sum of her children. It is also a metaphor of the motherland whose soul has become corrupted by capitalism. Capitalism has become the only logic that rules her nation, where all human relationships are mediated by money. The citizen does not act but is acted upon. In the poem “The Portrait of Mr. Pon Kagya,” the salaryman Mr. Pon Kagya does not sit on the chair but the chair sits on him; the pen grips him; the pay envelope thrusts him in his pocket. Objects have become subjects who have their way with this salaryman, who is powerless. While Choi’s poems may be despairing, they are simultaneously liberating because she writes in a language both ruthlessly direct and strangely surreal. She does not obfuscate her despair with elegant metaphors but confronts it with nightmarishly strange imagery. In her brutal investigation of her own pain and agony, she cries out for an alternate way of life.

Choi took a hiatus from poetry in 2001 because of her mental illness, but her reputation as a formidable poet in South Korea has only grown. She has published eight books of poetry: Love in This Age (1981), A Happy Diary (1984), The House of Memory (1989), My Grave Is Green (1993), Lovers (1999), Alone and Away (2010), Written on the Water (2011), and Empty Like an Empty Boat (2016). Choi has also translated many books into Korean, including Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, Max Picard’s The World of Silence, Paul Auster’s The Art of Hunger, and Erich Fromm’s The Art of Being. In 1994 she participated in the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. She has received the Daesan Literary Award (2010) and Jirisan Literary Award (2010) and is now regarded as one of the most important poets in Korea.

Cathy Park Hong is the author of the essay collection Minor Feelings, as well as three books of poems, most recently Engine Empire. She is the poetry editor of The New Republic.

From Cathy Park Hong’s preface to Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me, by Choi Seungja, translated from the Korean by Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong. © Action Books, 2020.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/35gURev

Comments

Post a Comment