Last week, I had the opportunity to visit the archive of the painter Dorothea Tanning, with whom my wife, the poet Brenda Shaughnessy, had had a twenty-year friendship, and who I had gotten to know toward the very end of her life. Dorothea, who died at a hundred and one in 2012, was profoundly intelligent, funny, mischievous, and in possession of her full creative powers almost until the very end. In her late eighties, when her hands were no longer steady enough to paint, she switched to poetry and published two extraordinary collections in her nineties. Her archive is housed in the Destina Foundation offices in downtown Manhattan. As I visited the space and spent some time with the work, I had a socially distant conversation with Dorothea’s archivist, Pam Johnson, who showed me some of the late works on display.

First a little background on Dorothea. She was born in Galesburg, Illinois, in 1910, and first gained notoriety in the early forties with what is still her most famous painting, the self-portrait Birthday. She made her way to New York as a young woman and fell in with the European surrealists who had fled the Nazis. One of them, Max Ernst, visited her studio in 1942 and was astounded by Birthday. That was the start of their thirty-four-year relationship and marriage, which would take them from New York to Sedona, Arizona, and back to Paris, before Dorothea settled in New York after Ernst’s death in 1976. She began as a surrealist, as Birthday, with its winged monkey, endless doors opening into the distance, and botanical dress, makes clear, but the late paintings and fabric sculptures on view in her archives were ample evidence that she moved far beyond her beginnings, into realms for which I’m not sure there’s a handy label.

I’m not going to get into the scholarship around the paintings or say too much to contextualize them in terms of art history—for that, you might look to Dorothea Tanning: Transformations, a new book by scholar Victoria Carruthers, which surveys Tanning’s life and work and is filled with excellent reproductions.

Instead, I want to share what it felt like to be so close to Dorothea’s art, to come so close to the brushstrokes I could almost touch them with my eyelashes; to stand back and take in whole vast canvases. Dorothea was a painter whose ambition and achievement were not sufficiently recognized, and these late works are among her most formidable and distinctive. The bodies she depicted—distorted, sexual, fantastical, blending and dissolving into and emerging out of their charged surroundings—were always visionary, but she grew into an artist just as interested in the materials themselves. In these late paintings paint becomes corporeal, inseparable from the limbs, torsos, and disguised faces that hover across her canvases, like a vaporous imagination released into the atmosphere of a room.

While she had her signature subjects (nude bodies, young women, dreamlike landscapes filled with symbolic objects and architecture), Dorothea was above all else an artist who never stopped growing. The works, like Birthday, for which she is best known are characterized by an almost photo-realistic surrealism, akin to the work of Ernst or Dali, and rooted in a kind of Pre-Raphaelite Romanticism. Over the course of her long career, her imagination merged with her medium, yielding unprecedented creations as much about the paint itself as about what she painted.

On her website, Dorothea is quoted explaining that the bright orbs in this painting “may have been flowers but also novas, tears, omens, God knows what, contending or conniving with our own ancestral shape in a place I’d give anything to know.” I love how this painting blends a kind of longing with a sense of ritual and work and nightmarish uncertainty.

Look at all that paint! Those brushstrokes flashing and undulating. It seems to me Dorothea accomplishes everything the abstract expressionists set out to do, but adds human (and animal) form and narrative, without giving anything away.

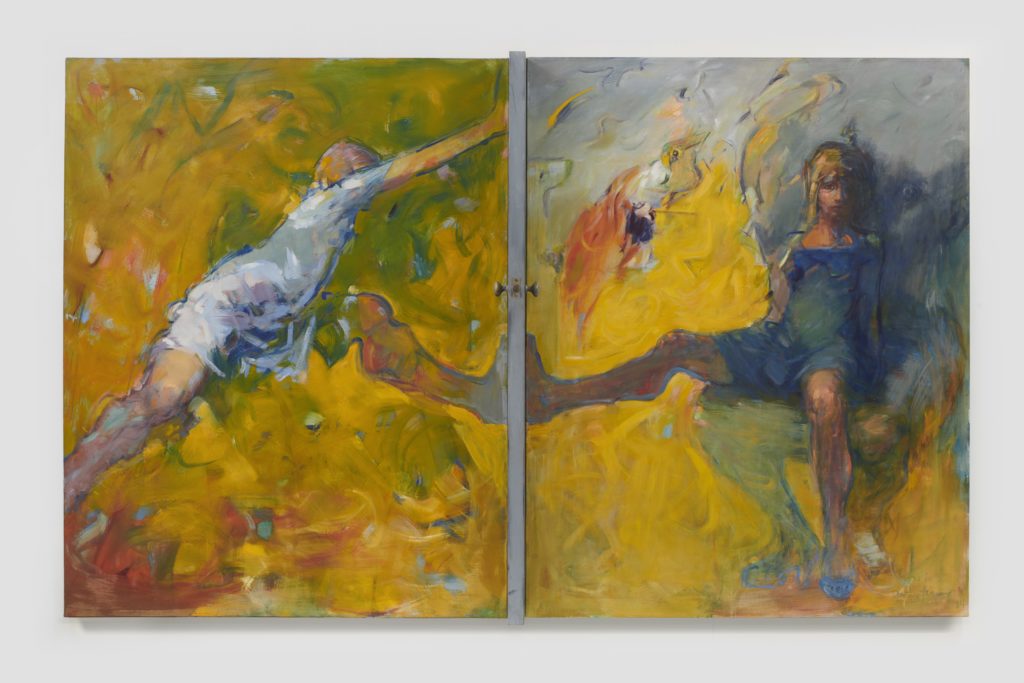

This is a major work in her oeuvre, another late painting, on a large canvas. Two young women strain to keep a door closed—well, one strains, while the other … sits with resolve. A miasma roils around them, which I can only characterize as externalized inner life.

Dorothea’s work had always been obsessed with textures. In earlier periods, abstract textures were rendered with photo-realistic detail, arching and sinewing throughout the canvases. But in her later work, the paint itself, glopped and glomming, overtakes the will to depict: the painting and its subject are synonymous.

Dorothea also did a great deal of fabric sculpture. And she loved dogs, painting them often. Despite the obvious seriousness of her work, it’s also full of humor. I think this may be the funniest thing she made, though that may have something to do with the fact that my family recently got a puppy. My eight-year-old daughter cracked up when I showed it to her.

This painting was, in part, an elegy for Ernst, a depiction of Dorothea’s grief, of a sense of the world that was left. It’s a pretty apocalyptic vision, though it’s not without a certain kind of dark levity. Here her dogs are talismans, caretakers, and also the very environment in which the figure resides; she is inseparable from them, an aspect of them as much as they are an aspect of her. Again, the imagination is externalized, and the boundaries between bodies and surroundings are in the process of dissolving.

What intrigues me most in this painting is the bit in this detail: the lightning etching its way out of or into the paint, the craggy mountains, a sort of castle, all of it merging with the fabric of the rest of the painting. What we feel, what we remember, what we want, what we need: inevitably, that’s what we see, and then try to see beyond, with more and less success, trapped by the imagination that frees us.

Craig Morgan Teicher is the digital director of The Paris Review and the author of several books, including The Trembling Answers: Poems and We Begin In Gladness: How Poets Progress.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2SgdDN9

Comments

Post a Comment