Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

On Sunday, the staff of The Paris Review was at the Brooklyn Book Festival, hawking our wares and slinging subscriptions.

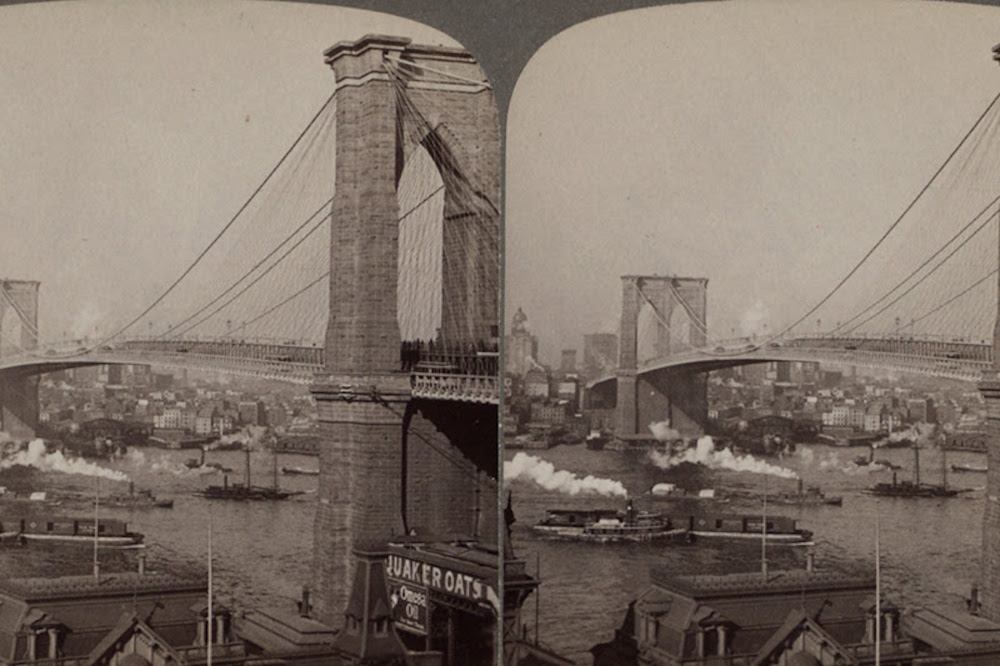

For those of you who live too far away to have stopped by our booth to say hello, we bring you David McCullough’s 1999 Art of Biography interview, where he recounts how he began writing his book The Great Bridge; Jonathan Lethem’s story “Tugboat Syndrome,” whose protagonist “grew up in the library of St. Vincent’s Home for Boys in downtown Brooklyn”; and Pam A. Parker’s poem “Brooklyn Crossing.”

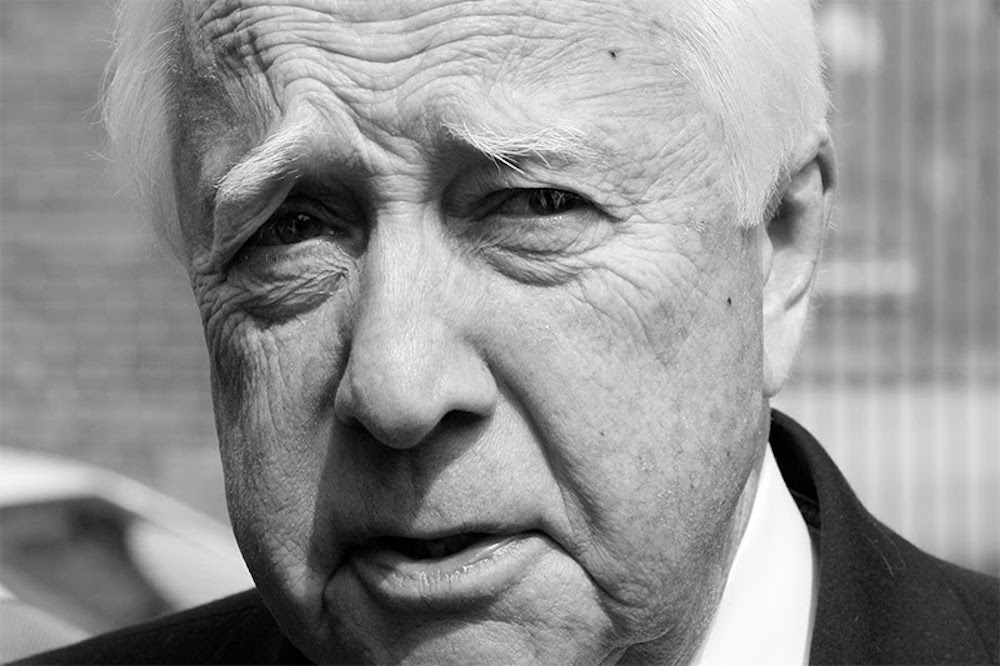

David McCullough, The Art of Biography No. 2

Issue no. 152 (Fall 1999)

One day I was having lunch in a German restaurant on the Lower East Side with an architect-engineer and a science writer. They started talking about what the builders of the Brooklyn Bridge didn’t know when they started it. The more they talked, the more I realized I had found my subject. I had lived in Brooklyn Heights and walked over the bridge many times; the Roeblings came from my part of Pennsylvania and I knew something about them because they plotted the course of the Pennsylvania Railroad through Johnstown. I left the restaurant and went straight to the Forty-second Street library and climbed those marble stairs to the third floor as if I had a jet engine on my back. There were over a hundred cards on the Brooklyn Bridge, but none described a book of the kind I had already begun blocking out in my mind. I went to Peter Schwed, my editor at Simon and Schuster, and said, I’ve got my next book.

Tugboat Syndrome

By Jonathan Lethem

Issue no. 151 (Summer 1999)

I grew up in the library of St. Vincent’s Home for Boys in downtown Brooklyn, on a street which serves as the off-ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge. There the Home faced eight lanes of traffic, lined by Brooklyn’s central sorting annex for the post office, a building that hummed and blinked all through the night, its gates groaning open to admit trucks bearing mountains of those mysterious items called letters; by the Burton Trade School for Automechanics, where hardened students attempting to set their lives dully straight spilled out twice a day for sandwich-and-beer breaks, overwhelming the cramped bodega next door; by a granite bust of Lafayette, indicating his point of entry into the Battle of Brooklyn; by a car lot surrounded by a high fence topped with wide curls of barbed wire and wind-whipped fluorescent flags, and by a red-brick Quaker meetinghouse that had presumably been there when the rest was farmland. In short, this jumble of stuff at the clotted entrance to the ancient, battered borough was officially Nowhere, a place strenuously ignored in passing through to Somewhere Else. Until rescued by Frank Minna I lived, as I said, in the library.

Brooklyn Crossing

By Pam A. Parker

Issue no. 125 (Winter 1992)

The masts are mostly gone, Walt. Pleasure-sailors

ply the harbor, piloting fiberglass forty-footers

down from the North Shore, one at the wheel,

one to haul sail and sit, staring over the water’s face.

A swimmer, strong and lucky, might make it,

cutting an angle across the current, ebb up, flood down.

Jumpers, too, are rare, these days: a train is more reliable,

that third, electrified rail, half-covered, always visible …

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2MICXWY

Comments

Post a Comment